Franciszek Jarecki from Poland to Denmark, March 1953

On the morning of March 5, 1953, two planes took off from the Polish air base Slupsk near the Baltic Sea. These were the most advanced Soviet MiG-15bis jet fighters at the time. The pilot of one of them was Franciszek Jarecki, a 22-year-old honors graduate of the prestigious Air Force Academy in Demblin.

Franciszek Jarecki next to a training glider, early 1950s.

Magazyn TVN24 / «Бабель»

The pilots were supposed to fly along the coast and return to the base. While carrying out a U-turn maneuver, Jarecki sharply descended at full speed and flew towards the Danish island of Bornholm, located approximately one hundred kilometers away. He flew to the island in about seven minutes. He heard shouts in Russian on the radio and realized that eight planes had been launched to catch him. But Jarecki managed to fly to the island and land at the local airfield, where he surrendered to the border guards and asked for asylum. He recalled that before crossing Danish airspace, he shouted over the radio to his pursuers that he was "flying for medicine for Stalin." At that time, the Soviet dictator had been dying for several days, and finally, on March 5, 1953, he passed away.

The next day, there were two main news on the front pages of Western newspapers: the death of Stalin and the escape of a Polish pilot from behind the Iron Curtain on the newest Soviet fighter. American experts hastily arrived in Denmark and disassembled the MiG down to the cog. In a few weeks, the plane was returned to Poland. And Jarecki moved to the USA, received American citizenship and a $50,000 bonus for handing over the plane to the Americans. In his homeland, Jarecki was sentenced to death in absentia, and his mother was imprisoned for three years. He came to Poland only once — in 2005.

Footage of Jareckiʼs arrival in the United States and the MiG-15bis fighter jet in which he escaped from Poland, 1953.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

In the West, Jarecki in numerous interviews talked about life in socialist Poland. He told stories about anti-American propaganda, the terror of secret services, camps for political prisoners, food shortages, Russian superiority over Poles, and an atmosphere of total suspicion and constant denunciations. He recalled how he spied on fellow pilots "at the behest of the party." And when he found out that a "supervisor" was attached to him, he decided to escape.

Pilots of socialist countries all over the world were urged to follow Jareckiʼs example. Over the next few years, three more Poles escaped in MiGs. Two — along Jareckiʼs route to the island of Bornholm, the third one — to Sweden.

Flyer with Jareckiʼs story encouraging North Korean pilots to escape, 1953.

Wikimedia / «Бабель»

No Kum-sok from North to South Korea, September 1953

The story of Jareckiʼs escape worked faster than the American special services expected. On the morning of September 21, 1953, 21-year-old North Korean Air Force pilot No Kum-sok took off in a Soviet MiG-15 fighter from an airfield near Pyongyang. In 17 minutes, he landed at Kimpo Air Base in South Korea, scaring the American military. Kum-sok was actually lucky that the Americans had temporarily shut down the radar that morning for routine maintenance, or he might have been shot down.

No Kum-sok at a military base in South Korea after escaping, 1953.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

But Kum-sok got out of the plane, defiantly tore up a photo of then-North Korean leader Kim Il-sung and said he was tired of living among "red liars." For US intelligence, it was quite a stroke of luck. Finally, they got their hands on the same Soviet fighter that tormented the Americans during the Korean War. They categorically refused to return the plane. Whatʼs more, American pilots were already flying it in a few months. This aircraft is now on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Ohio. And in the USSR, just in case, authorities decided not to send MiG fighters of the next generation to North Korea.

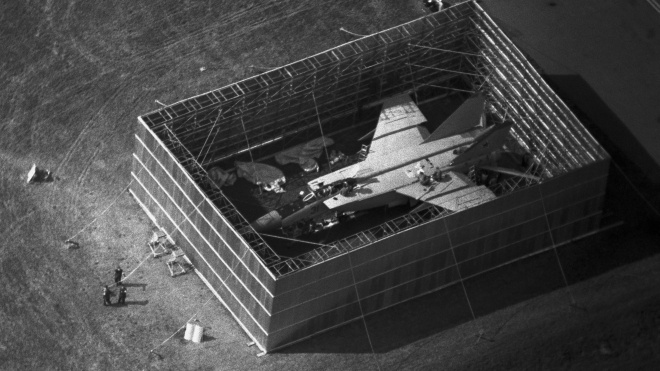

The MiG-15 in which No Kum-sok escaped, in a hangar at Gimpo Air Base, September 1953. The Americans are preparing for the first flight of the MiG-15, on which No Kum-sok escaped. The aircraft was already marked with US Air Force markings, October 16, 1953.

USAF / «Бабель»; Getty Images / «Babel'»

No Kum-sok received a huge reward at that time — $100 thousand, moved to the USA and changed his name to Kenneth Rowe. He received a higher technical education and worked as a leading aviation engineer at Boeing, General Motors, General Electric, and Lockheed. He was joined by his mother, who managed to escape from North Korea. His father died during the Korean War, and the rest of his relatives were repressed. Later, No Kum-sok learned that after his escape, five pilots with whom he served together were shot.

No Kum-sok shakes hands with US Vice President Richard Nixon, May 1954.

Wikimedia / «Бабель»

Munir Redfa from Iraq to Israel, 1966

Since 1961, the USSR began to supply the newest MiG-21 fighter at that time to Syria, Egypt, Iraq and other "friendly" Arab countries. The relations of these states with Israel were worsening, another war was brewing. So the Mossad decided to take possession of this plane at any cost. For several years, all attempts were unsuccessful, in Egypt Israeli agents were even arrested and sentenced to long imprisonment.

Finally, the Mossad was lucky enough to recruit one of the best pilots of the Iraqi Air Force, Munir Redfa, who flew the MiG-21. The fact that Redfa came from a Christian family and complained about religious persecution in Iraq played into the hands of the Israelis. Redfa was offered a million dollars and Israeli citizenship. But he put forward one more condition — to take his entire family out of Iraq. When the Israelis did this, Redfa began to wait for an opportunity to escape. The chance fell during a training flight on August 16, 1966. Redfa flew through Jordan, which was Syrian ally, so the local military did not suspect anything at first. And then he unexpectedly turned towards Israel. At the border, he was met by Israeli fighter jets and escorted to the airfield. The escape took about 25 minutes.

Israelis display the MiG-21 on which Munir Redfa escaped, 1966.

Wikimedia / «Бабель»

After careful examining and training flights, the plane was transferred to the USA. Later, the Americans returned it to the Israelis. Redfa first settled in Israel, and at the end of the 1960s, together with the whole family, he moved to one of the countries of Western Europe.

The MiG-21 on which Munir Redfa escaped, with the symbolic flight number 007, is on display at the Israel Air Force Museum at Hatzerim Air Base, 2006.

Wikimedia / «Бабель»

The Israelis studied all the strengths and weaknesses of the Soviet aircraft so well that already in April 1967 they shot down six Syrian MiG-21s in air combat without losing a single fighter of their own. They used the received information no less successfully during the victorious Six-Day War in June 1967.

An Egyptian MiG destroyed during the Six Day War, June 1967.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Viktor Belenko from the USSR to Japan, 1976

On the morning of September 6, 1976, several planes took off from a Soviet air base near Vladivostok for a training flight. Unexpectedly, one of the pilots, senior lieutenant Viktor Belenko, stopped communicating, sharply descended to a height of about 30 meters and disappeared from the radar. He flew over the sea until his plane entered Japanese airspace. Belenko headed to the military base on the island of Hokkaido. However, he ran out of fuel, so he landed at the islandʼs civilian airfield, nearly crashing into a passenger Boeing that was about to take off. Then Belenko surrendered to the police and asked for political asylum.

Belenkoʼs plane skidded off the runway while landing at Hakodate Airport on the island of Hokkaido on September 6, 1976.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

At first, the Japanese did not understand what kind of aircraft they had got their hands on. Only after Belenkoʼs explanations did they understand that it was the latest and top-secret Soviet MiG-25P interceptor with a lot of secret equipment on board. Then American specialists were called, they began to disassemble the plane and soon transported it to the US military base for further research. In November 1976, after tense negotiations, the plane was returned to the Soviet Union in disassembled form — in 30 boxes.

The MiG-25P, on which Belenko escaped, is being dismantled at Khakodate Airport, September 8, 1976. A partially disassembled MiG-25P is loaded onto a transport plane to be delivered to a US military base on September 24, 1976.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Belenko received political asylum in the USA, and later, by a special decree of the then President Jimmy Carter, he also received American citizenship. He said that he had decided to escape, having become disillusioned with the Soviet regime and especially with the Soviet army. After thorough checks, Belenko became a military consultant for the US Air Force. Once he was invited to the military base of American pilots to see their life and service organization. "If my regiment had looked for even five minutes at what I saw today, a revolution would have started," he said as he left the air base. Belenko completely severed ties with his wife and other relatives, he remarried in the USA. He is now 76 years old and says he is happy in the United States.

Japanese police escort Belenko on a flight to the United States, September 9, 1976.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

For the USSR, Belenkoʼs escape on a secret fighter jet became a huge scandal. Therefore, the official version of Soviet propaganda sounded like this: "Senior Lieutenant Belenko made a forced landing on Hokkaido due to lack of fuel and was criminally kidnapped by the Japanese authorities at the behest of Washington."

Alexandr Zuev from the USSR to Turkey, 1989

At the end of the 1980s, Alexandr Zuev, a 27-year-old captain of the USSR Air Force who served in Georgia, also became disillusioned with the Soviet regime. According to him, the last straw was the events of April 1989 in Tbilisi. Then Soviet paratroopers dispersed an anti-government protest near the parliament building with sapper shovels. 20 demonstrators were killed in the clashes, more than four thousand people were injured.

Military equipment near the parliament building in Tbilisi after the dispersal of demonstrators, April 9, 1989.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Zuev decided to steal the newest Soviet MiG-29 fighter jet at the time and developed an escape plan. On the night of May 20, 1989, he was on duty at the airfield. To all the technicians and pilots who were with him on the shift, he announced that his son was born and treated them to a cake with a lot of sleeping pills. When everyone fell asleep, Zuev cut the telephone wires in the control room and went to the runway. There he told the guard that he would replace him at the post. And when the guard left, Zuev began to prepare the plane for takeoff.

The Soviet MiG-29 fighter jet is shown to the Western public for the first time at the Farnborough Air Show in England on July 11, 1988.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

But then everything did not go according to plan. The guard did not go to the barracks, but to the next room, saw that everyone was sleeping, and decided to return to the airfield to report this to the senior officer, i.e. Zuev. There the guard saw that the captain was preparing the plane for an unauthorized departure. A firefight broke out between them, Zuev wounded the guard, but he himself received a bullet in his right hand. In the end, Zuev did take off. After that, he tried to shoot other planes on the runway so that they would not try to intercept him. But he could not, because in confusion he forgot to remove the external lock from the gun.

Alexandr Zuev in the cockpit of the plane.

Wikimedia / «Бабель»

Zuev flew more than 200 kilometers south across the Black Sea and landed at Trabzon Airport in Turkey. There he surrendered to the guards with the words: "Finally! I am an American!” The Turks returned the plane to the Soviet Union the very next day, but refused to hand over the fugitive pilot. Zuev first received political asylum, and soon he received US citizenship. He advised the US Air Force prior to Operation Desert Storm in the Persian Gulf. Zuev died in 2001 in a plane crash near Seattle during a training flight on a Soviet Yak-52 sports plane.

Translated from Ukrainian by Anton Semyzhenko.

Honest and truthful journalism is no less valuable than a top-secret weapon. Support Babel: 🔸 in hryvnia , 🔸 in cryptocurrency , 🔸 Patreon , 🔸 PayPal: [email protected].