In 1944, Hungary was occupied by Soviet troops. However, it was not possible to turn it into one of the countries of the social camp right away. In the first post-war elections, the Communist Party of Hungary under the leadership of the Stalinist Mátyás Rákosi won only 17% of the vote. So the communists had to go into opposition to the democratic multi-party coalition.

Then the newly created analogue of the Soviet KGB, the Hungarian secret police AVH, took up the case. Before the next parliamentary elections, Rakosiʼs political opponents were suppressed by intimidation, imprisonment and torture on trumped-up charges. The remnants of the Social Democrats were forced to unite with the Communists in the Hungarian Workersʼ Party, which came to power in the 1949 elections. Three months after the elections, the parliament adopted a new Constitution, which renamed the state the socialist Hungarian Peopleʼs Republic and finally established the principle of one-party rule.

Matias Rakosi (right) congratulates the leader of the Social Democrats Árpád Szakasits on their unification into a single party in 1948. In 1950, Szakasits was arrested on fabricated charges.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

In addition to the position of general secretary of the party, Rakosi also occupied the chair of the countryʼs prime minister. Having received the full power, he set out to copy the Stalinist regime in the smallest details: he nationalized industry, introduced five-year plans and forced collectivization for the peasants, fought against the Catholic Church and, of course, began mass repressions. Almost a million Hungarians (i.e. approximately 10% of the countryʼs population) were on the pen of the secret police. Members of every third or fourth family passed through the camps. In addition, according to Stalinist models, Rakosi organized purges in his immediate environment. For example, the Minister of Internal Affairs and AVH founder Rajk László was repressed. Later, the same fate befell his successor, the former first secretary of the Hungarian Communist Party János Kádár.

János Kadar (left) and Rajk László at the first national meeting of the Communist Party of Hungary, May 1945.

Wikimedia / «Бабель»

Such a policy did not bring anything good to the countryʼs economy. Already in the early 1950s, food shortages began — bread, sugar, flour, meat, etc. became scarce. An additional burden on Hungaryʼs economy was reparations, which it had to pay as a former ally of Germany. Sometimes these payments reached a quarter of GDP.

The situation improved somewhat in 1953 after Stalinʼs death. At the request of Moscow, the more moderate communist Imre Nagy was appointed prime minister of Hungary. He immediately began to implement reforms. He rolled back industrialization and eased the pressure on the peasants, reduced taxes and raised wages, and most importantly, he stopped political repression and announced a large-scale amnesty. Janos Kadar was among those amnestied. But Rakosi, who retained the position of head of the Communist Party, was not going to give up. After long behind-the-scenes intrigues, in 1955, Nagy was accused of "dangerous flirtation with liberalism", removed from the post of head of government and expelled from the party.

Imre Nagy speaks at a parliamentary session, with Mátyás Rákosi sitting next to him, October 21, 1954.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Rakosi appointed his puppet prime minister and began to restore the Stalinist course. However, this was out of the question. The Kremlin also added fuel to the fire. In February 1956, at the height of the struggle for power, the first secretary of the Communist Party of the USSR Nikita Khrushchev gave a historic speech on the cult of Stalinʼs personality and mass repressions.

Footage of Khrushchevʼs speech at the 20th Party Congress, where he read a report on the debunking of Stalinʼs personality cult, February 1956.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

First of all, it was a blow against Khrushchevʼs political opponents from the Stalinist clan. However, the echo of this report passed through all the countries of the social camp. In June 1956, strikes by workers in East Berlin and Poznań, Poland turned into uprisings, which the Soviet army suppressed with tanks. In order to prevent such a thing from happening in Hungary, the Kremlin in July 1956 decided to remove Rakosi from the position of first secretary of the local Communist Party, away from sin. But it was too late. Protest moods spread in the country — primarily among students and intelligentsia, and workers joined them closer to autumn.

In the afternoon of October 23, 1956, approximately 20 000 students and intellectuals took to the streets of Budapest. They demanded, among other things, the withdrawal of Soviet troops from the country and a review of relations with the USSR, the establishment of a new government headed by Imre Nagy and the holding of free elections on a multi-party basis, the introduction of democratic freedoms, including freedom of speech, and the dissolution of the AVH secret police.

A Hungarian student makes political demands to the authorities during a rally, October 1956.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

In the evening, there were almost 200 000 demonstrators on the streets of the capital. However, the party leadership refused to negotiate, calling the speech "hostile and chauvinistic." Then the demonstrators single-handedly fulfilled one of their demands — they demolished the eight-meter statue of Stalin in the center of Budapest. And then they went to storm the radio station to announce their demands for the whole country. There, the first clashes with security forces took place and the first dead and wounded on both sides appeared. However, most of the Hungarian police and military quickly sided with the protesters and opened their armories to them. So the rally turned into an uprising.

The head of the monument to Stalin, which was toppled by Hungarian demonstrators in Budapest, on October 24, 1956.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

In an attempt to appease the rebels, the party leadership reinstated Imre Nagy as prime minister. Later, Janos Kadar was hastily elected as the partyʼs first secretary. The Kremlin decided to send almost 6 000 soldiers with several hundred tanks and armored personnel carriers to Budapest. The Soviet leadership expected that it would be possible to suppress the uprising, which it was in the summer in East Berlin. But everything turned out the other way around.

The turning point was the events of October 25. During a multi-thousand-strong rally in the square under the parliament building in the capital, where many women and children had gathered, shooting began. Until now, it is not known for certain who opened fire — whether it was the AVH agents or the Soviet military. Panic set in, and Soviet tanks began to plow into buildings and people. Almost a hundred demonstrators were killed that day. Real hostilities began in the city. Rebels threw Molotov cocktails at tanks and fired at military columns. Reinforcements did not help, the Soviet military proved to be unprepared for such armed resistance, got lost in the streets of Budapest without maps and were forced to flee the city, leaving their equipment behind. Thus, the rebels ended up with almost a hundred fully operational tanks.

Hungarian insurgents and the military attached to them drive through Budapest on captured Soviet equipment, 1956.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

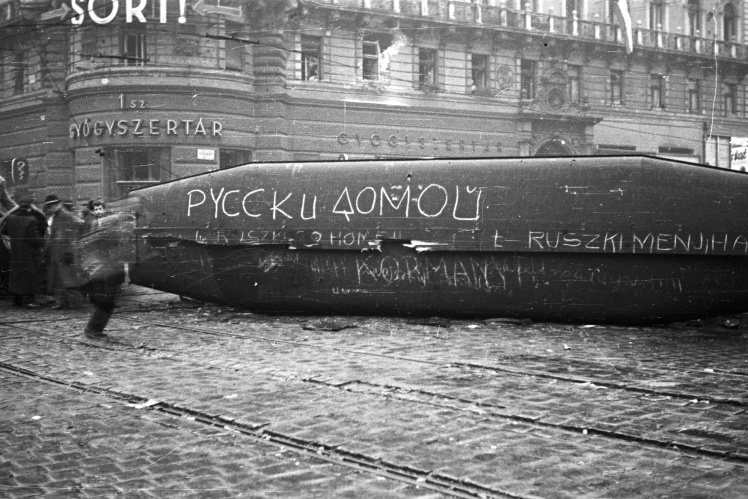

After the shooting of demonstrators in Budapest, the uprising spread throughout the country. Angry insurgents broke into institutions and staged lynchings of party members and agents of the secret police. The symbol of the revolution became the Hungarian flag with the Soviet coat of arms cut out of the middle, and the slogan was the call "Russians, get plumb out of here!"

A revolutionary flag with a carved Soviet coat of arms on a street in Budapest, 1956. A sign urging Russians to get away on an overturned tram, Budapest, 1956. A member of the Hungarian secret police surrounded by protesters during the anti-communist uprising in Budapest, late October-early November 1956.

Getty Images / «Babel'»; Wikimedia / «Бабель»

At this time, Nagy tried to somehow normalize the situation. He quickly formed a new government and appealed to Moscow to withdraw the troops, and to the rebels to stop the violence. By October 29, the Soviet troops withdrew from Budapest, the fighting in the streets stopped. Nagy dissolved the AVH, opened prisons and restored the multiparty system. It would seem that the revolution has won.

However, the Kremlin was not going to give up so easily. In the first days after the retreat from Budapest, the Soviet leadership did not yet dare to launch a new assault, fearing military intervention from the West. However, the international situation was not in favour of Hungary. Great Britain and France intervened in the Suez conflict on October 29, 1956. The head of the White House Dwight Eisenhower was in the last week of the election campaign. He was going for his second presidential term and least of all wanted to start a military conflict with the USSR. The US Secretary of State John Foster, known for his tough stance on communism, told Soviet leaders that the US "does not see these countries [Hungary and Poland] as potential military allies."

The US Secretary of State John Foster during an interview in October 1956.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

The last formal difficulty was that the USSR had to oppose the legitimate Hungarian government, which it itself recognized as legitimate. Then the Kremlin came up with a scheme that is still being followed. The uprising in Hungary was declared a "counter-revolutionary rebellion inspired by agents of the West." An alternative government was assembled from fugitive Hungarian communists under the chairmanship of Janos Kadar, who fled the capital on November 1, as soon as the smell of roasting began. A huge military group was drawn to the Hungarian borders. Soldiers and officers were told that they were going to fight "fascists". It got to the point that some thought that they would go to Berlin, others that they would be sent to the Suez Canal.

On November 1, 1956, Prime Minister Nagy asked the Soviet ambassador to Hungary Yuriy Andropov, why the USSR was accumulating troops on its eastern borders. He lied that no invasion was planned, and that it was all in order to "protect the Soviet population in the border strip." On the evening of November 3, Hungarian Defense Minister Pal Maleter, together with members of his staff, having received guarantees of security and inviolability from the Kremlin, went to the headquarters of the Soviet command to discuss the conditions for the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Hungary. They were immediately arrested there and sent to Moscow.

Hungarian rebels burn Soviet literature and portraits of Stalin, October 31, 1956. Hungarian rebels in Budapest during the lull after the retreat of Soviet troops, late October — early November 1956. A column of Soviet military equipment on the streets of Budapest, November 1956.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

On the night of October 3-4, a Soviet group numbering more than 60 000 soldiers and about 3,000 units of armored vehicles and artillery crossed the Hungarian border. They staged a real storming of Budapest, like during the World War II, with airstrikes and artillery training. They were opposed by approximately 50 000 rebels.

In desperation, Imre Nagy declared the countryʼs withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact Organization — the Soviet analogue of NATO — declared a neutral non-aligned status and asked the UN to support Hungaryʼs sovereignty. But it was too late. At a meeting of the UN Security Council on November 4, the USSR used the right of veto and blocked the resolution that demanded the withdrawal of troops. The UN General Assembly adopted a resolution in which it "expressed regret over the repression against the Hungarian people and the Soviet occupation." And the then Secretary General of NATO, the Belgian Paul-Henri Spaak, generally called the Hungarian uprising "the collective suicide of the people." Soviet General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev later bragged in an interview, comparing Western aid to a "hangerʼs rope."

Janos Kadar (right) meets Nikita Khrushchev (center) in Budapest, 1960.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

After fierce fighting, until November 11, Soviet troops captured Budapest and suppressed the revolution. 2 500-3 000 Hungarian rebels and more than 300 civilians died in the fighting. Losses of the Soviet army reached approximately 700 soldiers. Nagy and the remnants of his government hid in the Yugoslav embassy. At the end of November, they were lured out of there by deception — they promised an unhindered departure from the country, but they were immediately arrested on their way out. And then repressions began. More than 20 000 people received various terms in prisons and concentration camps, about 300 were sentenced to death. Former Prime Minister Imre Nagy was among them. He was executed by order of the new Hungarian ruler Janos Kadar with the consent of the Kremlin. Almost 200 000 Hungarians were forced to flee the country from persecution.

Hungarians in an Austrian refugee camp, November 1956. Hungarian refugees cry after crossing the Austrian border, November 16, 1956. A Hungarian family flees to the border with Austria, 1956.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

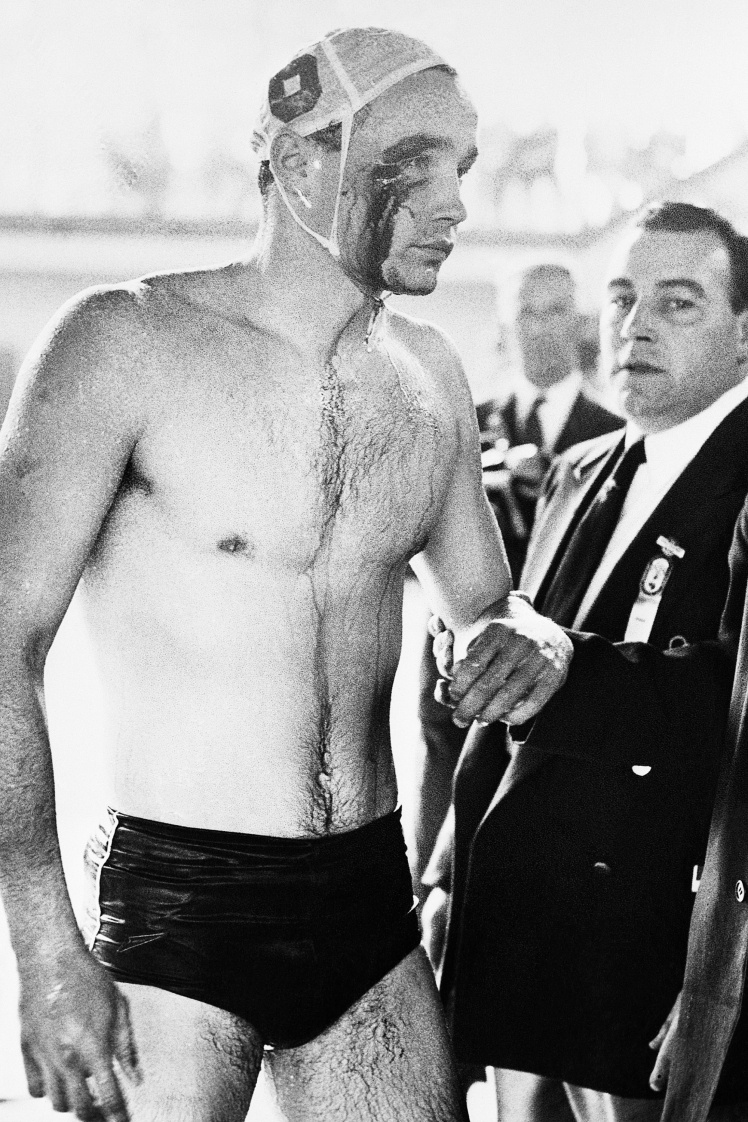

The last act of the Soviet-Hungarian confrontation in 1956 took place after the suppression of the uprising at the Olympics in Melbourne. As a sign of protest, the Hungarian national team went to the opening ceremony with the Hungarian flag without the socialist coat of arms. And the semi-final water polo match between the teams of Hungary and the USSR turned into a bloody fight. In the end, almost half of the Hungarian athletes did not return home after the Olympics.

A bloody Hungarian water polo player after a match with Soviet athletes at the Olympics in Melbourne, December 8, 1956. The Hungarian national team at the opening ceremony of the Olympics in Melbourne, November 22, 1956.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Ukraine closely followed the events in Hungary and hoped that they would cause a domino effect that would bring down the Soviet regime. Protest sentiment spread from Uzhhorod and Lviv to Donetsk and Luhansk, which at that time was called Voroshilovgrad. And it was not only among students and liberal community. A shopkeeper in Stryi Pavlo Luchynskyi rode a bicycle through the city and shouted: "Ukrainians! Take up arms and rise to the struggle against the Soviet authorities!"

A native of Kyiv Oleksandr Onishchenko declared: "One fine day, the people will put an end to this regime everywhere. It is worth awakening the fire — and the same will happen in Hungary. You canʼt live like that. This is not life, but an occupation in the full sense." The hairdresser of the Luhansk Regional Music and Drama Theater Mykola Dubenko said: "Itʼs good that there was an uprising in Hungary. Let them beat the communists, and others will follow the Hungarians." Subsequently, they were all arrested by the KGB along with other "unreliable" people.

As for the Russians, the words of the professor of history of the Moscow State University Sergei Dmitriev written secretly in his diary are still relevant today: "It is a shame to be a Russian. It is a shame because, although the Hungarians are oppressed not by the Russian people, but by the communist government of the USSR, the Russian people are silent and behave like a people of slaves. A nation that oppresses other nations cannot be free."

Soviet soldiers on the streets of Budapest after the suppression of the uprising, November 12, 1956.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Babel remains an independent media thanks to your support: https://babel.ua/donate