Katyn massacre, April-May 1940

On September 1, 1939, Nazi Germany invaded Poland, starting World War II. While the Polish army was trying to restrain the German offensive from the west, early in the morning of September 17, Soviet troops invaded Poland.

The Soviet Union attacked Poland without declaring war, violating several treaties it had signed with the Poles. For example, the Peace Treaty of 1921 and the Non-Aggression Pact between the USSR and Poland in 1932, which not long before the invasion was extended by both governments until 1945.

Soviet propaganda explained the reasons for the invasion as follows: after the German attack, Poland ceased to exist as a state, so Soviet troops were forced to cross the border to protect the inhabitants of Western Ukraine and Western Belarus. In reality, though, the question of the joint division of Polish territories between Germany and the Soviet Union was resolved in August 1939, when the Soviet-German Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was signed.

Soviet political worker, battalion commissar Filip Borovensky (in a center in a leather raincoat) at the talks on the partition of Poland with German officers in Brest (nowadays Belarus), September 20, 1939.

The Polish military tried to resist the Soviet army, but the forces were too unequal. By the end of September 1939, the USSR and Germany occupied and divided the territories of Poland. The occupiers practiced terror in the occupied territories — they shot not only the military and police, but also women and children. Between a quarter and half a million Polish citizens were taken prisoner by the Soviets.

Eventually, some of the prisoners were released, about 40,000 people were transferred to Germany, and more than 25 people were sent to camps in Siberia and special settlements in northern Kazakhstan. The rest of the prisoners, mostly Polish officers, were distributed in camps in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. At first, they were even allowed to write letters to their relatives, which they sent via the International Red Cross. But in April-May 1940, the letters stopped coming. All inquiries about the fate of the prisoners of war, including by the Polish government that emigrated to London, were given vague answers by the Soviet leadership or simply ignored.

Captured Polish military, 1939.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

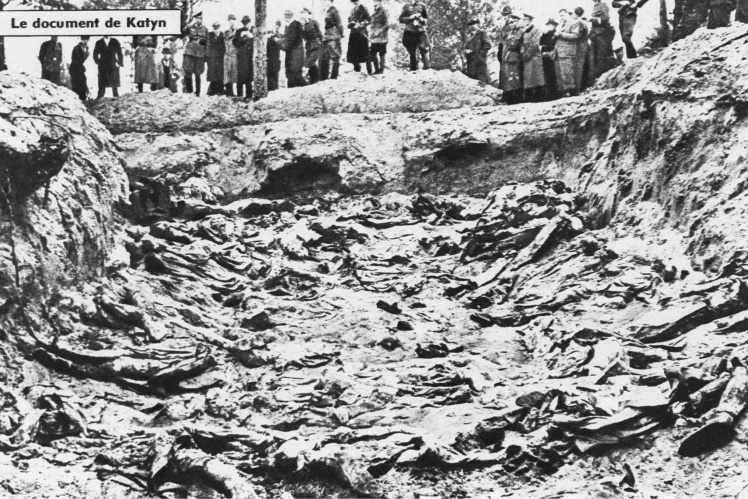

In 1941, Germany attacked its former Soviet ally. And in 1943, after the occupation of the Smolensk oblast, the Germans discovered the mass burial of Poles in the Katyn forest. Many had their hands tied behind their backs and bags on their heads. Examination has shown that they were shot in the spring of 1940 before the arrival of the Germans.

The Germans are examining bodies found in the Katyn Forest in 1943. Mass burial in the Katyn forest, discovered by the Germans after the occupation of the Smolensk oblast in 1943.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Nevertheless, the Soviet Union denied involvement in the shooting and even tried to shift the blame on the Nazis at the Nuremberg Tribunal for War Criminals of the Third Reich. But they failed. Prosecutors found that the Germans were not involved in the crime. However, this did not prevent the USSR from denying its guilt until 1990, when documents proving the Soviet Unionʼs involvement in the executions of Poles were found in Soviet archives.

It turned out that in March 1940, at the suggestion of NKVD Chairman Lavrentiy Beria, the highest governing body of the USSR, the Politburo, approved the execution of more than 20,000 Polish prisoners of war. Mass shootings took place not only in Katyn, but also in Tver, Kharkiv, and camps and prisons in western Ukraine and Belarus.

In the 1990s, first a Soviet and later a Russian prosecutorʼs office conducted an investigation. The Katyn massacre was declared a "crime of the Stalinist regime", the case was closed in connection with the deaths of all perpetrators, and the investigation was classified. The Poles werenʼt satisfied with this. Relatives of the victims appealed to the European Court of Human Rights. In 2012, the ECHR recognized the Katyn massacre as a war crime by the Soviet leadership and security forces, and ruled that the Russian authorities had not conducted an effective investigation. But Russia refused to investigate the crime further.

Cemetery of reburied victims of the Katyn massacre, 1988.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Mass killings of prisoners in western Ukraine, June-July 1941

In the autumn of 1939, the USSR the western Ukrainian territories, which at that time were part of Poland. Soviet propaganda presented this as the "liberation and reunification" of Ukrainian lands and even drew parallels with the 1919 Act of Unity. So at first some Ukrainians even welcomed Soviet troops.

Soviet troops distribute propaganda newspapers to residents of western Ukraine and Belarus during the September 1939 invasion of Poland.

But soon the Soviet authorities switched on the same thing as in other occupied Ukrainian territories — mass terror. Politicians, religious figures, intellectuals, officials, ex-servicemen, activists of the national liberation movement, entrepreneurs from the local "bourgeoisie" and peasants who refused to join collective farms were imprisoned and executed on popular charges of counter-revolutionary activities.

In the early summer of 1941, 26 prisons in western Ukraine were overcrowded. As of June 10, 1941, they held about 73,000 people, despite a general limit of just over 30,000.

After the German attack on the USSR, the NKVD leadership initially tried to evacuate the prisoners. But the frontline was approaching fast. So a telegram with instructions came from Moscow, from Beria himself: to shoot all those who were imprisoned with charges of counter-revolutionary activities. This was relevant for most of the prisoners.

Bodies of executed Ukrainians in the yard of Lviv prison, July 1941. Ukrainians search for the bodies of relatives in the yard of a prison in Lviv, July 1941.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

In the end, the evacuation was carried out in only a few places, and most of those evacuated never reached the destination. Transport was most often used to move out Soviet command and valuables. Most of the prisoners were sent on foot on the so-called "death marches". Along the way, they were shot by escorts, and sometimes bombed by German aircraft, taking for retreating Soviet units. Those who were taken away by rail were no luckier — they were burned or blown up along with the cars. And at the Zalishchyky station in the Ternopil oblast, 14 cars with political prisoners were dropped from the destroyed bridge into the Dnister River. There were 50 to 70 people in each car, none of whom survived.

Mass shootings began in almost all prisons in cities of western Ukraine: Lutsk, Stanislav, Ternopil, Rivne, Dubno, Kovel, Drohobych, Volodymyr-Volynsky, and many others.

One of the most horrible tragedies took place in Lviv, where, according to various estimates, between 3,000 and 5,000 people were shot dead in four NKVD prisons. Raids started in the city itself, anyone could be detained on the street and declared a spy and saboteur.

A Lviv resident tries to find relatives among those killed in the yard of the Lviv prison in July 1941.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Initially, people were shot in the usual way for the NKVD — a shot to the back of the head in a special cell. Many were tortured before their deaths. But the front was fast approaching, so the shootings were intensified — people were driven into cells and shot from machine guns through the window for food delivery or threw grenades there. The dead were first taken out by trucks and buried in special places, and later buried in courtyards and basements of prisons.

Occupying Lviv, the Germans purposely opened the doors of prisons and exhumed the bodies of those killed for anti-Soviet propaganda. And Soviet propaganda, in turn, tried to hang this crime on the Nazis, as in the case of the execution of Polish prisoners of war. Such actions of the Soviet punitive authorities fall into the category of war crimes under the rules of international law of the time — the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, compliance with which was constantly declared by the Soviet Union during World War II.

Lontsky Prison Memorial Museum in Lviv.

Wikimedia

Prison cells in the Lontsky Prison. A woman in front of the entrance to the Lontsky Prison Memorial Museum.

Wikimedia

Deportation of Crimean Tatars, May 1944

In April 1944, Soviet troops drove the Germans out of the Crimea. And the first thing the Soviet government did was not rebuilding the war-torn peninsula, but staging mass repressions.

Forced deportation of the population in the USSR has been practiced since the 1920s. One of the best-known examples of this practice was the deportation of Crimean Tatars.

Crimean Tatar Festival, early 1940s.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Soviet propaganda accused the entire Crimean Tatar people of "betrayal of the Motherland and total collaborationism" during the Nazi occupation of the peninsula. It was claimed that about 20,000 Crimean Tatars sided with the Germans. Even if to believe these figures, according to Soviet Official data, more than 25,000 members of this nation fought in the Soviet army and guerrilla units. Some of them were awarded the highest award — Hero of the Soviet Union. And compared to other official figures for collaborators, for example, about 400,000 Russians fought on Hitlerʼs side.

But the question of ethnic cleansing had already been resolved, and on May 11, 1944, Stalin personally signed a resolution of the State Defense Committee about the organization of the deportation of Crimean Tatars. The NKVD-controlled forced eviction operation started early in the morning of 18 May.

Everyone was deported — children, women, the elderly and people with disabilities. Only 15-20 minutes were given to the families to get their belongings. Officially, each family had the right to take up to 500 kilograms of luggage, but in reality they were allowed to take only hand luggage, and sometimes nothing at all. People were taken by truck to railway stations. From there they were immediately or in two or three days sent in clogged freight cars to remote areas of Central Asia, the Urals and Siberia.

Crimean Tatars during the re-eviction from Crimea in the 1960s.

Wikimedia

The main phrase of the deportation operation ended on the evening of May 20. Almost 70 echelons were sent east from the Crimea. In the few weeks spent on the road, about eight thousand people, mostly old people and children, died. The remaining Crimean Tatars were deported during the deportation of Armenians, Greeks and Bulgarians from the peninsula in late June of that year. Even those Crimean Tatars who served in the Soviet army were deported after demobilization.

In special settlements they lived in difficult conditions — in dugouts and barracks, almost without water and food. In the first years after deportation, 20 to 40 percent of the deportees died, or about a third to half of the Crimean Tatar people. The Kremlin tried to erase all traces of the existence of Crimean Tatars — rewrote the history of Crimea and renamed all Crimean Tatar names on the peninsula, banned the language, even the name "Crimean Tatars" was removed from all official documents and encyclopedias. The nationality was banned.

Crimean Tatars after deportation to logging works, 1952. Crimean Tatars deported to the Molotov (now Perm) oblast of Russia, 1948.

Wikimedia

After the deportation of Crimean Tatars, migrants were sent to the peninsula on Stalinʼs orders, primarily from the Russian hinterland — Kursk, Voronezh, Belgorod oblasts, the Volga region and the northern areas. But the benefits of this were small, because these people werenʼt accustomed to the Crimean climate, didnʼt know the local features of agriculture in the mountains and steppes. Crimeaʼs economy and infrastructure remained in decline until it was handed over to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1954.

Crimean Tatars were forbidden to return to the peninsula until 1989. Ukraine, Latvia, Lithuania and Canada have recognized the deportation of Crimean Tatars as genocide. But Russia, as the successor to the USSR, did not conduct any investigation into this crime and did not pay any compensation. Moreover, by occupying the peninsula in 2014, the Russian authorities started repressions against the Crimean Tatar population.

We tell about historical events honestly and objectively. Support Babel: 🔸 Donate in hryvnia🔸 in cryptocurrency🔸 via PayPal: [email protected]

Pro-Ukrainian rally of activists with Crimean Tatar flags in front of the parliament in Simferopol shortly before the Russian occupation of Crimea, February 26, 2014.

Getty Images / «Babel'»