Graduates of Ukrainian studies courses at the District Council of Trade Unions in Luhansk, 1925-1928.

In the early 1920s, the Bolsheviks controlled most of the territories of modern Ukraine. But the vast majority of the population did not support them. The harsh policy of "war communism" was not liked by either the peasantry or the intelligentsia. Therefore, nationalization and prodrazverstka were replaced by the New Economic Policy.

This was not enough. In 1917-1921, the process of national revival began in Ukraine. In the resolution of April 22, 1917, the Central Rada, the parliament of the Ukrainian Peopleʼs Republic, determined that it conducts its activities "standing on the principle of Ukrainization of all [spheres of] life in Ukraine." This trend continued under the Hetmanate and the Directory.

Ukrainization campaign poster, early 1920s.

Wikimedia

In order not to lose control over Ukraine, Moscow decided to lead the process. One of its main ideologues was Joseph Stalin, at that time Peopleʼs Commissar for Nationalities Affairs of the USSR. In addition, there were also foreign policy tasks. First, to form a positive image of the USSR on the international arena as a state in which the right of nations to self-determination is provided. Secondly, to attract to our side Ukrainians who lived outside the Soviet Union — in exile and on ethnic lands belonging to other states. After the First World War, Galicia and Western Volhynia became part of Poland, Bukovina and Bessarabia — in Romania, Transcarpathia — in Czechoslovakia. The Bolsheviks hoped to later annex these territories to the USSR.

A similar situation existed not only in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, but also in other national republics. Therefore, in April 1923, at the 12th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks in Moscow, the policy of "indigenization" was announced. The state authorities of the national republics had to switch to their native language and develop national culture. Also, representatives of the indigenous population were nominated to the party leadership.

Kyiv City Pawn Shop, sign in Ukrainian, 1920—1928.

In Ukraine, this policy took the form of "Ukrainization" and became the most extensive among all republics. Later, it even spread to the territories that were not part of the USSR — to the Kuban and the North Caucasus. On the twenty-seventh of July 1923, the Council of Peopleʼs Commissars of the Ukrainian SSR issued a decree "On Measures for Ukrainization of School-Educational and Cultural-Educational Institutions." It provided for the transition to the Ukrainian language of teaching in educational institutions. On August 1 of the same year, the resolution "On ensuring the equality of languages and on promoting the development of Ukrainian culture" was issued.

The policy of "Ukrainization" was successfully implemented in education, culture, science and the press. At the beginning of the 1930s, the number of schools with the Ukrainian language of instruction exceeded 80 percent, two-thirds of higher education institutions and even some military units switched to the Ukrainian language. The Ukrainian-language press accounted for 89 percent of all newspaper circulation in the republic, three-quarters of theaters gave performances in Ukrainian. Ukrainian films were shot at Odesa and Kyiv film studios. The works of classics of Ukrainian literature and young authors were published.

Documents of the great-grandfather and grandfather of Babelʼs senior literary editor Vira Solntseva, Kyiv, early 1930s. All notes are in Ukrainian.

Scientific works on Ukrainian linguistics, dictionaries of technical and business vocabulary were published. Advanced European scientific manuals and textbooks were translated into Ukrainian. The discipline "Ukrainian studies" was taught not only in universities of the USSR, but also in the Kuban in Russia. A new Ukrainian spelling appeared, in which the deforming influence of the Russian language was weakened — "Kharkivsky" spelling or "Skrypnykivka", after the surname of one of its initiators, Peopleʼs Commissar of Education Mykola Skrypnyk. Some of his points were returned in the 2019 edition of Ukrainian spelling.

The foreign policy calculations of the Bolsheviks worked. The popularity and influence of the Communist Party of Western Ukraine grew in Galicia in the 1920s. Ukrainian emigrants from Berlin, Vienna, Prague, and Paris also believed in the seriousness of the "Ukrainization" direction and began to return to the USSR. Among them were, for example, ex-speaker of the parliament of the Ukrainian Peopleʼs Republic Mykhailo Hrushevskyi and former general of the Ukrainian army Yuriy Tyutyunnyk. But among the Ukrainian intelligentsia there were those who were wary of such a drastic change in the policy of the Soviet government.

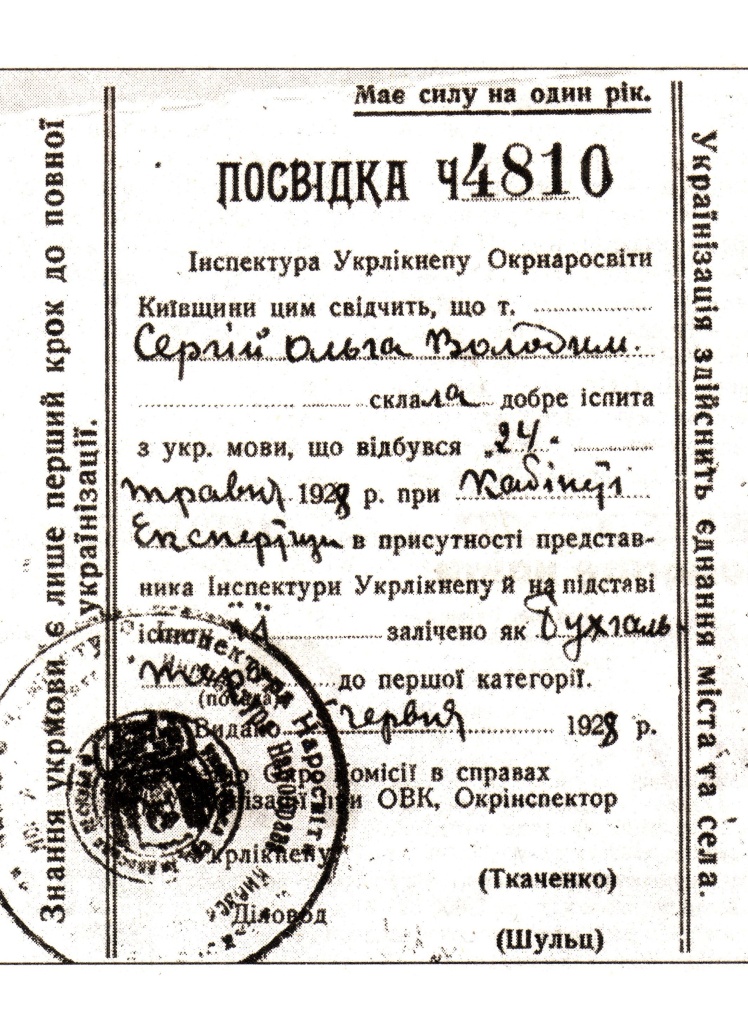

The State Bank in Kyiv in the early 1920s. Now the building of the National Bank of Ukraine. The signs are in Ukrainian. Certificate of passing the Ukrainian language exams by an accountant, Kyiv region, 1928.

Wikimedia

But the party leadership and officials of the Ukrainian SSR were in no hurry to switch to the Ukrainian language. Back in 1923, language courses were opened for them. By the summer of next year, those who did not learn Ukrainian were threatened with dismissal. And for control, they even introduced the institute of Ukrainization inspectors, who could appear unannounced to inspect any state institution.

By 1925, it was possible to Ukrainize only about 15 percent of paperwork in the central authorities. All because there were practically no ethnic Ukrainians in the party leadership of the USSR at that time. Most were Russians or representatives of other nationalities. In the 1920s and early 1930s, the post of first secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist party of Ukraine was held by: German Emmanuel Kviring, Jew Lazar Kaganovich, and Pole Stanislav Kosior. Therefore, a kind of paradox emerged: the demand to start "Ukrainization" came from Moscow, and the local authorities in Kharkiv, which was then the capital of the Ukrainian SSR, sabotaged it in every way and passed the "correct" resolutions just to tick the box.

Members of the Communist Party branch at the Donetsk Institute of Public Education (modern Taras Shevchenko Luhansk National University), Luhansk, 1927.

If Kaganovich at least tried to learn the Ukrainian language, then, for example, Kviring and his second secretary Dmytro Lebid were categorically against the policy of "Ukrainization". They considered Russian culture to be advanced, while Ukrainian culture was called "inferior village culture."

Then the Ukrainian national communists — Oleksandr Shumskyi, a native of the Zhytomyr region, and Mykola Skrypnyk, a native of the Donetsk region — took up the case. During the 1920s and early 1930s, they were peopleʼs commissars of education of the USSR.

Skrypnyk tried especially hard. From the beginning of the 1920s, he was Peopleʼs Commissar of Internal Affairs, then Peopleʼs Commissar of Justice and Prosecutor General, and in 1927 he replaced Shumsky as Peopleʼs Commissar of Education. He strengthened the requirements for knowledge of the Ukrainian language for officials, and those who did not cope, he personally fired.

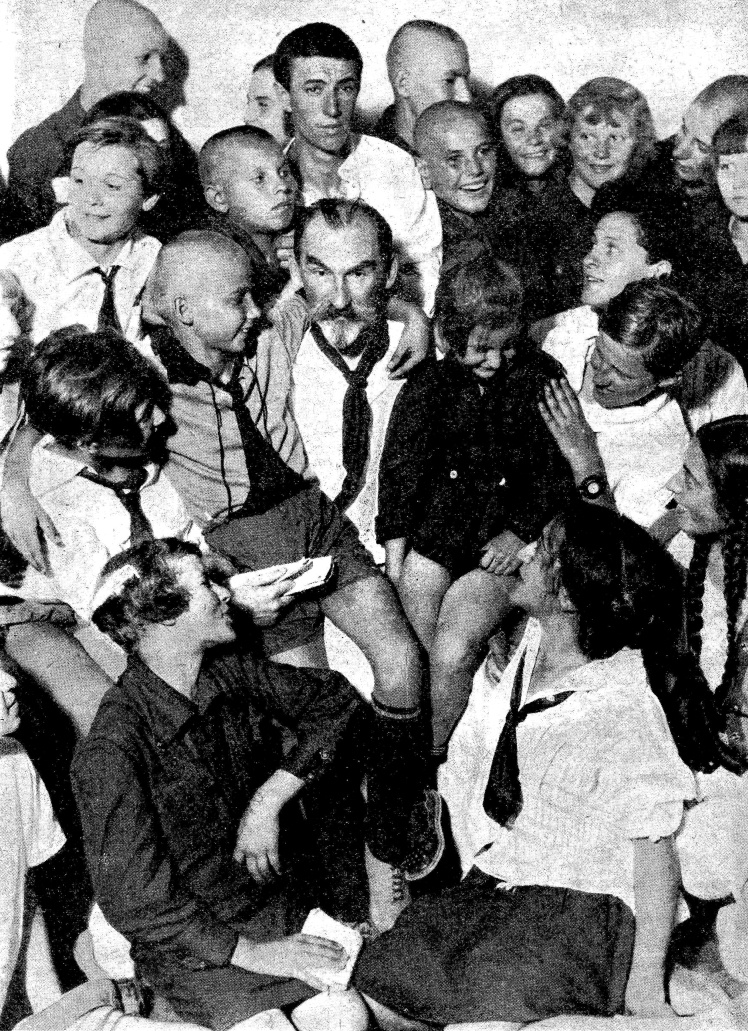

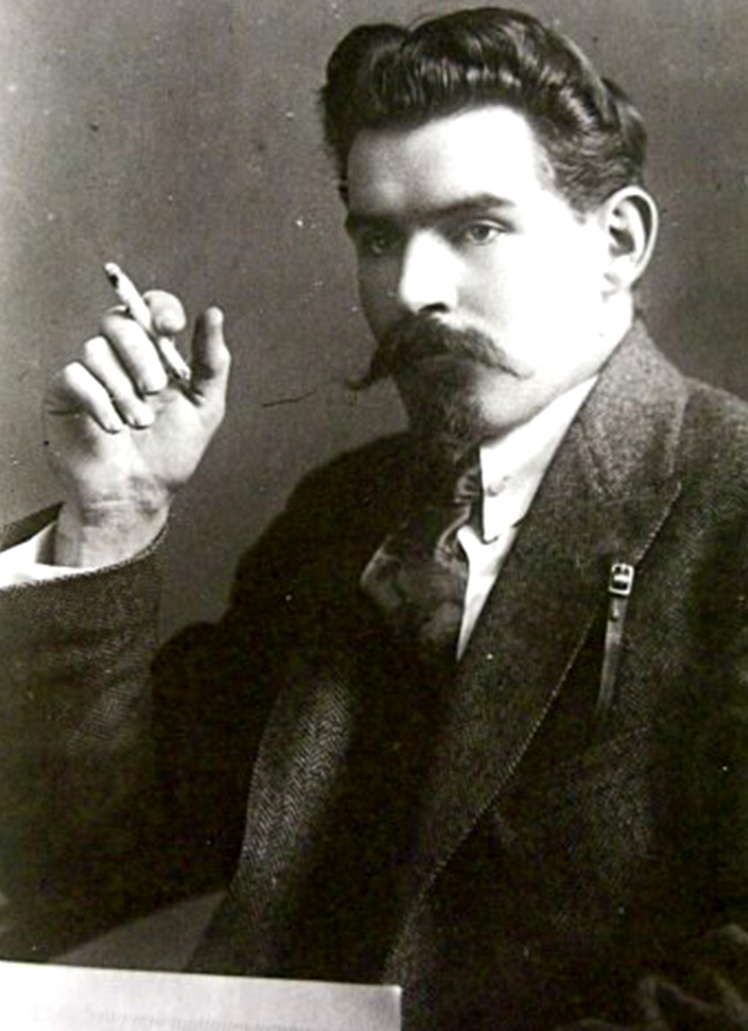

"The pioneer of Bolshevysm in Ukraine, Comrade M. O. Skrypnyk, together with other pioneers." Photo from "Universal Magazine", 1929. Oleksandr Shumskyi, early 1920s.

Wikimedia

A special resolution of the Peopleʼs Commissariat of Education ordered to open more Ukrainian schools and libraries, to provide the population with newspapers and magazines. Teacher training was highlighted as a separate line. Another problem that the Peopleʼs Commissar of Education drew attention to was the army, where everyone spoke only Russian. Skrypnyk demanded that educational work be carried out among the soldiers in the Ukrainian language and supervised the Kharkiv "School of Red Officers", which by the beginning of the 1930s had trained about a thousand Ukrainian command staff.

Skrypnyk was a convinced Bolshevik and mercilessly fought against any enemies of the Soviet government. But at the same time, he constantly emphasized the independence of Ukrainian culture from Russian and was not afraid to demonstrate his position among party members. He clashed with Stalin, Peopleʼs Commissar of Nationalities. And sometimes he even went to Moscow with a translator and spoke there in Ukrainian.

Leadership of the district committee of the Communist Party in Luhansk, 1930.

In the late 1920s, Moscow realized that "Ukrainization" had already gone too far and could become a threat to the regime. The liberal policy was replaced by a repressive one. Fabricated trials of the intelligentsia, purges in the party apparatus and the army, exiles and executions began.

At the beginning of the 1930s, Shumskyi and Skrypnyk, the main leaders of "Ukrainization", were also repressed. Shumskyi was accused of "national evasion" and sent to Solovky camp, and then killed on Stalinʼs personal order. Skrypnyk was publicly criticized at party meetings. After one of the meetings, at which he was once again accused of nationalism, Skrypnyk shot himself in his office.

In December 1932, the leaders of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the government of the USSR declared that "Ukrainization is being carried out incorrectly." And in the fall of the following year in Kharkiv, at the plenum of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, the policy of "Ukrainization" was recognized as dangerous and a decision was made to stop it.

The trial in the case of the "Union for the Liberation of Ukraine" — a mythical organization invented in 1929 by the authorities of the State Department of the Ukrainian SSR to discredit the Ukrainian scientific intelligentsia. There were 45 defendants at the court in Kharkiv, later about 500 people were tried in this case.

Wikimedia

Translated from Ukrainian by Anton Semyzhenko.

We write in Ukrainian without instructions "from above", and your donations will help us write in the future: 🔸 in hryvnia, 🔸 Buy Me a Coffee, 🔸 Patreon, 🔸 PayPal: [email protected].