How the Osage tribe became rich

The Wazhazhe Indians, nicknamed "Osage" by the French colonizers, lived for many hundreds of years in the Ohio River Valley in approximately the territory of the modern state of Kentucky. In the 17th century, due to constant wars with the Cherokee, they began to move to the west. Eventually they settled at the intersection of the modern states of Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma and Arkansas.

The US government gradually restricted their lands until, in 1825, they moved further west to Kansas. There, the tribe survived several smallpox epidemics, the people suffered — the Osage used to live mainly by hunting buffalo, and in Kansas they were forced to switch to agriculture. At the same time, smallpox epidemics brought the tribe closer to the Catholic Church — missionaries organized medical assistance. So the Osage, who until then mostly ignored the church, gradually began to accept Christianity.

In 1870, the government again decided to relocate the Osage, this time to the territory of the modern state of Oklahoma, to the Indian Territory. Then the Osage got lucky for the first time — the administration of President Ulysses Grant offered a good price for their land in Kansas.

With this money, the Osage bought new land in Oklahoma. Usually, the American government, giving the Indians land for reservation, reserved the right to dispose of the resources of this land under certain conditions. But the Osage, having paid the money, became the full owners of their 5,900 square kilometer plot. At that time, no one cared for that, because these lands were barren and cheap.

In 1894, the Osages were lucky for the second time — in the reservation lands they found significant reserves of oil. The government allowed private companies to extract it, and the Indians received 10% of the income. In 1907, the state of Oklahoma was formed, with a separate Osage County in it. Then the head chief of the tribe, James Bigheart, made a new agreement with the government. According to it, each of the 2,229 members of the tribe had the right to a plot of land and an equal share of oil revenues.

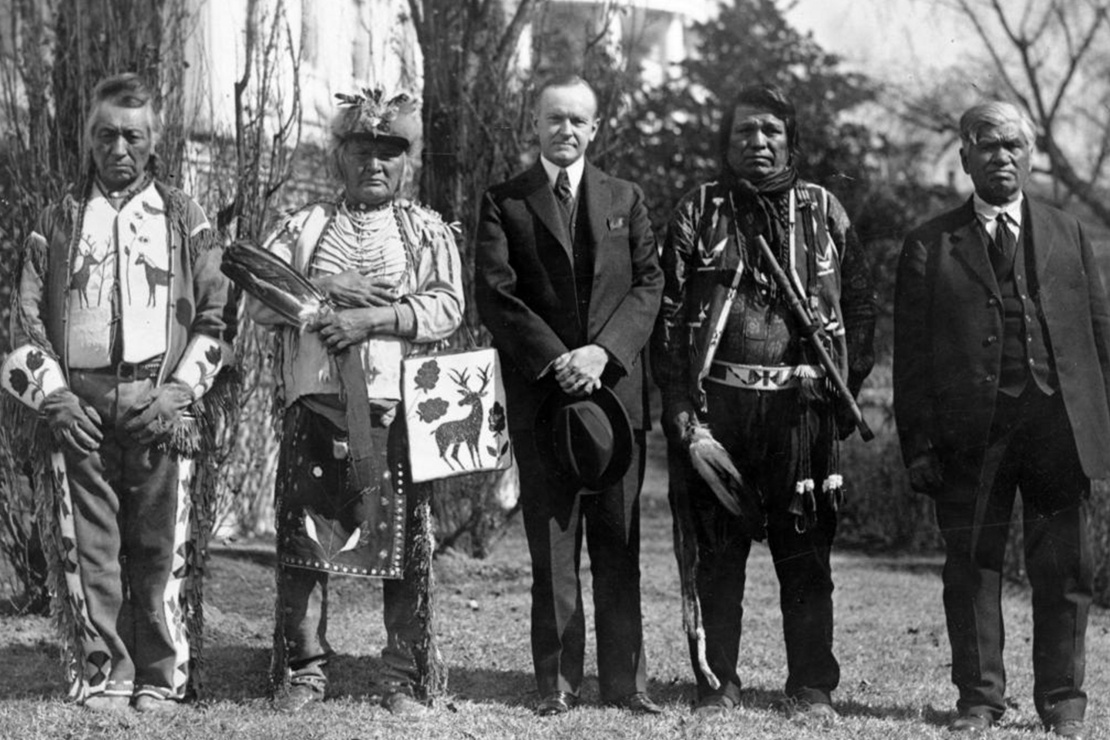

US President Calvin Coolidge with Osage men after signing the Indian Citizenship Act, which gave all Native American people equal rights with other citizens, 1924.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

At the beginning of the 1920s, the price of oil began to rise. Along with it, the incomes of the Indians increased — each member of the tribe received $13 thousand a year. And the entire tribe together earned up to $30 million a year — huge money for the United States at that time. The reservation looked more and more elegant. For example, the jewelry company Tiffany & Co. opened a store there.

Already in 1921, the US Congress slightly reduced the income of the tribe by adopting a law according to which the Osage had to prove in court their "competence" to dispose of such large amounts of money. Otherwise, a "financial guardian" was appointed to them. The courts made such guardians white lawyers and businessmen who often cheated the Indians and appropriated part of their money. In 1921, about 8,000 people lived in the town of Pohaska, which was the center of the reservation. And there were as many lawyers as there were in Oklahoma City, where 140,000 people lived. Most of these lawyers were "guardians" who lived off the tribeʼs oil money.

This shady business could not exist for long — the Osage were not naive savages, they gradually learned to understand laws and documents. Also, there were lawyers who helped them. Already in 1924, many "guardians" ended up in courts, some were forced to return the money. By that time, they had stolen a total of approximately $8 million.

Oil fields in Osage County, Oklahoma, circa 1918-1919. Three Osage men sit in front of a store, Pohaska, Oklahoma, circa 1918-1919.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Fraudsters who wanted to finally take control of the tribeʼs income faced an obstacle in the form of one of the provisions of the 1907 Agreement — the right to a share of the oil income could not be sold or gifted. It belonged exclusively to a member of the tribe and his heirs in the family line. This was done precisely so that the income did not go beyond the boundaries of the tribe.

There was only one way to get a share of the proceeds forever, and that was to become a member of an Osage family and then kill all of the new relatives. And one of the first to come up with such a scheme was a local Oklahoma businessman, William Gale.

The beginning of the Reign of Terror

William Gale came from Texas, in his youth he worked as a cowboy, driving cattle from Texas to Kansas through the Indian territories. By 1900, having collected money, he settled in the territory of modern Oklahoma and founded his own ranch. Gradually, Gale became the main local tycoon — he simultaneously owned a controlling stake in a regional bank, had shares in various businesses — from stores to funeral homes, held the position of reserve assistant sheriff. His own ranch by 1917 had grown to 5,000 acres, and he leased another 45,000 acres from the Indians.

At that time, Gale was considered a respected businessman, and he called himself "the king of the Osage hills." Further investigation will conclude that he made most of his fortune through fraudulent methods. But in the 1910s it was still a long way from that. Gale successfully built the image of a friend and reliable business partner of the Osages, had many useful connections in the tribal council. Although in private conversations he always spoke disparagingly about Indians and claimed that they get their money unfairly, because these riches should belong to white people and to him personally.

William Gale

Getty Images / «Babel'»

In 1917, Gale married his 24-year-old nephew Ernest Burkhart to a 30-year-old Indian woman, Molly Kyle. He had chosen the couple with a criminal plan already in mind — Molly had diabetes, so Gale hoped she wouldnʼt live too long. But even here Gale played it safe — he put Molly under the care of his doctors, who periodically gave her a little bit of poison under the guise of anti-diabetic medicine.

The bride had many healthy relatives who also had to be removed. Strange deaths began in Mollyʼs family. In 1918, her sister Minnie died suddenly — doctors could not name the exact cause. And on May 27, 1921, the body of Mollyʼs second sister, Anna Brown, was found. She was killed by a shot in the head, but the body was badly decomposed, so the local law enforcement officers did not even begin to investigate it closely and closed the case as death due to alcohol poisoning. A few weeks later, the body of Annaʼs cousin, Charles Whitehorn, was found and he was also shot. Two months later, Molly, Minnie and Annaʼs mother, Lizzie Kyle, died of a strange illness. In 1923, another cousin of the sisters, Henry Roan, was killed. He was found in his own car with a bullet in his head.

Left to right: Lizzie Kyle, Rita Smith, Molly Barkhart.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Mollyʼs third sister, Rita Smith, remained. Her husband, Bill, had long suspected that the deaths in the family were not random, and little by little began to question and pressure the police. On May 10, 1923, the house of the Smith family was destroyed by a powerful explosion. Rita and her maid, Nettie, died on the spot, and Bill died four days later in the hospital.

The tribal council also conducted its own investigation. Members of Molly Kyleʼs family were not the only Native Americans in the county who began to die suddenly. By 1923, there were dozens of such cases.

George Bigheart, the nephew of the same chief who in 1907 made an agreement with the government, was a friend and neighbor of William Gale, he was even his "financial guardian". On June 28, 1923, Bigheart was admitted to the hospital with strange symptoms, and before that he had been drinking whiskey that Gale had given him. Lawyer William Vaughan came to him in the hospital, to whom George told that he knew the culprits of the deaths and could prove it. What happened next is not known for sure, but Vaughan disappeared the next morning. His body was later found with a fractured skull. Bigheart also died in the hospital on the same morning.

Bill and Rita Smithʼs home in Fairfield, Oklahoma. The ruins of the Smith family house after the explosion, 1923.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Investigation, trial and consequences

The local law enforcement officers were surprisingly not interested in all these events, they investigated almost nothing and did not combine them into a single case. Only one of them, police detective James Monroe Pyle, thought otherwise. In 1923, having enlisted the support of the tribe, he contacted the Bureau of Investigation. Edgar Hoover, who had become director of the Bureau a year earlier, took Pyleʼs story seriously and sent special agent Tom White to Oklahoma. He gathered a team, like in a movie: an experienced former sheriff; a former Texas Ranger who shot and fought well; a former insurance agent who was a master of reincarnation and negotiation; the mysterious Ute Indian John Wren, who had previously been a Bureau spy among Mexican revolutionaries. Also joining the team were agents John Barger and Frank Smith, who had handled the preliminary analysis of the case and knew Osage County well.

White, Barger and Smith worked openly and conducted a public investigation. The other four worked undercover, pretending to be a cattle buyer, an insurance agent, a doctor and an oil prospector. They gradually learned a lot about life in Osage County. For example, that William Gale is the leader of a whole criminal gang, which includes his relatives and ranch workers. And that it was Gale who somehow got the insurance payout for Henry Roanʼs death. And that among the local bandits and adventurers there is a whole market of hired killers who take orders for Osages. And itʼs not just Gale who uses it.

White collected evidence for two years. It turned out that Galeʼs gang hired thugs from the side for the murders. The tactics were quite correct — they were mostly robbers who did not live long. For example, the Smith family home was blown up by Asa Kirby, who was killed in a shootout during a store robbery that same year. And Henry Grammer, the middleman who hired Kirby on Galeʼs behalf, died soon after in a car accident. But on the other hand, it didnʼt make sense for the mercenaries to fence off Gale, so Cale Morrison, who killed Anna Brown, eventually gave a comprehensive account of how it was. Galeʼs accomplice John Ramsey confessed to the murder of Henry Roan.

In 1926, Gale, Ernest Burkhart and John Ramsey found themselves in court. And another problem arose there — Gale could always say that the robbers and bandits were simply deceiving him, a respectable philanthropist and businessman. Then the investigators decided to hit the weakest link in the Gale family — young Burkhart. And it worked out. Junior Burkhart told the whole story of how Gale had been gradually killing his wife Mollyʼs family by the hands of various people, and Ernest himself had helped him.

William Gale and John Ramsey (center) in the custody of US Marshals, 1926.

Wikimedia

For so many murders, the accused were threatened with the gallows, but their "correct" skin color played a role — Gale, Burkhart and Ramsey received life terms. Burkhart was released on parole in 1937 after serving 11 years. And Gale and Ramsey were released in 1947, after 21 years in prison. However, in 1940, Burkhart robbed the house of his relative and went behind bars again, where he remained until 1959. Gale died in 1962, and Burkhart lived until 1986. During this time, he somehow managed to fully rehabilitate himself from the affair and return to the Osage, despite the protests of the Indians. Molly divorced Burkhart during the trial, married another man in 1928, and died in 1937 of complications from diabetes.

Agent Tom White resigned from the Bureau in 1931 and became the warden of the Leavenworth prison in Kansas, where Gale and Burkhart were then imprisoned. He died in 1971. Detective James Pyle, who once initiated the investigation, was unable to work in Osage — local officials and businessmen considered him a traitor and harassed him. He eventually moved to Arizona, where he worked until his death in 1942.

In general, many Osages died in the first half of the 1920s. Modern researchers say about more than 60 murders and more than a hundred mysterious deaths that no one investigated. How many such deaths were on the conscience of the Gale gang, and how many were committed by criminals who acted according to the same scheme, is unknown. The murder of George Bigheart and attorney William Vaughn was never solved, and Gale was never formally charged.

In the 1930s, Edgar Hoover used the Osage murder case as one of the illustrations that local governments in the US are often corrupt and unable to bring to justice such "kings" as William Gale. Therefore, it is important to create a powerful federal bureau with broad powers. In 1935, the FBI was created on the basis of the Bureau of Investigation, and Hoover became its first director.

Report from The New York Times of Osage, January 17, 1926 issue.

Are the Osage still getting oil revenue?

Yes, although it is not a lot of money. Now the owner of the share can get about $16 thousand a year, which is not so much in the modern USA. In addition, the proceeds are still divided into 2,229 parts, which are now the shares of a single company, Osage Mineral Estate. And now there are more Osages — 13 thousand, six of which live in Oklahoma. Therefore, income per person is often even lower now.

In 2022, tribal lawyers and journalists obtained documents from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and found that a quarter of all shares — 550 of the 2,229 — are not owned by the Osage. Sometimes there is nothing criminal about it. For example, the Osage family bequeathed 2.3% of the shares to the Oklahoma Historical Society, which spends this money on an educational center for Native American youth. But sometimes it is not at all clear to whom the money went. For example, part of the shares until 2012 somehow belonged to a boarding house for people with disabilities, which closed in 1994. Almost $200,000 in 18 years went nowhere.

Local investment companies Sabine Royalty Trust and The Hefner Company said they had no idea they owned any interest in Osage Oil and never received the money. It is not known who received them.

These stories were not news to the Osage. Back in 2015, Osage businessman Charles Pratt told reporters that he personally visited the addresses of some rights holders and saw closed offices of defunct gasket companies. Earlier, in 2011, the tribe sought compensation of $380 million from the US government for the fact that the US authorities did not fulfill the terms of the 1907 treaty and could not establish effective resource management. At the same time, all owners of shares received compensation, even those who are not members of the tribe.

The Osage oil money lawsuits are now ongoing. Some rights holders are willing to return the shares to the tribe, but it is too complicated from a legal point of view. Thatʼs why the tribeʼs lawyers are pushing for a transparent procedure that will make it easier to do this.

Former Osage Nation Museum director Kathryn Red Korn points to a photo of her mother in a copy of David Grennʼs book The Flower Moon Killers, Sept. 29, 2023.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

The independent press also played a role in the investigation of the murders in Osage, which did not let the law enforcement officers forget about the case. Therefore, it is never important to support it: 🔸 in UAH, 🔸 in cryptocurrency, 🔸 Patreon, 🔸 PayPal: [email protected]