Despite mutual claims, Ukrainians and Poles had a common enemy. Since the declaration of independence of Poland and Ukraine at the end of the 1910s, relations between them have been far from friendly. The Poles tried to seize Galicia and generally planned to expand the territory to the borders of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1772, that is, to take almost the entire Right Bank Ukraine.

At the beginning of 1919, the West Ukrainian Peopleʼs Republic and the Ukrainian Peopleʼs Republic proclaimed the Act of Unity. But in reality the situation was completely bad. In addition to the Poles, Ukraine also had to fight with the Bolsheviks and the White Guard monarchists. In the fall of 1919, the Ukrainian Peopleʼs Republic actually turned into a state without a territory, trapped in the Kamianets-Podilsky area by the Polish, Red, and White armies. The Ukrainian leadership understood that it was necessary to negotiate with someone. And the head of the UNR Symon Petlyura decided to choose the best of the worst options — Poland.

From left to right: Polish General Antony Listovsky, Commander-in-Chief of the Army of the Ukrainian Peopleʼs Republic Simon Petlyura and Ukrainian Colonels Volodymyr Salskyi and Marko Bezruchko in Berdychev, April 1920.

Wikimedia / «Бабель»

The head of Poland at the time, Józef Pilsudski, feared that Russia, whether Bolshevik or monarchical, would not limit itself to annexing Ukraine. And the only possible ally for Poland remained, in fact, the Ukrainian Peopleʼs Republic. Pilsudski could hardly count on the military intervention of the Entente countries, tired of the First World War.

After the failure of the White Guard general Anton Denikinʼs campaign on Moscow in December 1919, the Bolsheviks remained the main threat. After that, the Ukrainian-Polish negotiations intensified and ended with the conclusion of the secret Warsaw Pact in April 1920. According to its terms, Poland recognized Ukraineʼs right to independence and undertook to liberate Ukrainian territory from the Bolsheviks through joint military efforts. In exchange for this, Petlyura agreed to recognize the Ukrainian-Polish border along the Zbruch River, that is, Galicia and part of Volynia were to remain Polish.

Józef Pilsudski (center left) with Symon Petliura among Polish and Ukrainian officers in Stanyslaviv (now Ivano-Frankivsk), September 1920.

Wikimedia / «Бабель»

This agreement was criticized on both sides. Polish National Democrats accused Pilsudski of giving up all the lands of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and spoiling relations with the Russians instead of focusing on the main enemy, Germany. Petliura was criticized by his closest associates in the UNR. And Galician Ukrainians were so offended that they tore up the Act of Unity. Minister of Justice of the UNR and an experienced lawyer, Serhiy Shelukhin, emphasized that this contract was drawn up in a legally illiterate manner on the part of the Ukrainian side. He warned that some nuances will allow the Poles to interpret this agreement as they wish.

The Bolsheviks did not intend to limit themselves to Poland. Slogans sounded in the Kremlin about "bringing happiness to the working people with bayonets through the corpse of bourgeois Poland." That is, to organize a revolution and establish Soviet power in Germany, and then in other European countries, in order to eventually "water the red horses from the Seine" and "plant a red flag over London."

Plans for the Sovietization of Europe were not so far-fetched. In Germany, after the defeat in the First World War, the left movement gained strength. And in Hungary in the spring of 1919, local communists led by Bela Kun, following the Bolshevik model, seized power and proclaimed the creation of the Hungarian Soviet Republic. Kun was openly waiting for armed help from the Kremlin. Moreover, he tried to export communism to neighboring Slovakia. In the summer, the Slovak Soviet Republic with its capital in Prešov and Košice existed for several weeks in its southern and eastern territories.

Hungarian communists in Budapest, 1919.

Wikimedia / «Бабель»

So the Soviet commanders Mikhail Tukhachevsky, Semyon Budyonny and Kliment Voroshilov planned to break through the Polish defenses and capture the city of Danzig with a swift blow from the north in order to block the aid routes from the Entente. By the end of the summer of 1920, the Bolsheviks were going to take Warsaw, and then go to the German borders and break through to Hungary.

Newsreel of the Red Army during the Soviet-Polish War, in the last frames Semyon Budyonny gives a speech to the soldiers, 1919-1920.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

During 1920, the military initiative passed from one to another. At the end of April, almost 20,000 Polish and 15,000 Ukrainian soldiers forced their way into Zbruch and went on the offensive. They managed to quickly push back the Bolshevik army. Already on May 7, Polish-Ukrainian troops entered Kyiv. In two days they organized a joint parade on Khreschatyk. The Poles did not want to advance further, and the Ukrainians lacked their own strength to do so.

Polish-Ukrainian troops on Khreshchatyk in Kyiv, May 7, 1920.

Wikimedia / «Бабель»

In June 1920, the Bolsheviks pulled up their reserves and launched a counteroffensive. Now the Polish-Ukrainian forces were rapidly retreating to the west. At the beginning of July, the Bolsheviks reached the Zbruch River, and at the beginning of August they were already approaching Warsaw. The forces of the Western Front under the command of Mikhail Tukhachevsky had to capture the Polish capital. The Bolsheviks had previously created a puppet Provisional Revolutionary Committee of Poland, which was supposed to take over power in Warsaw and announce the creation of the Polish Soviet Republic. At that time, foreign embassies were leaving the capital of Poland en masse.

Newsreel of the Polish army during the war with the Bolsheviks, 1919-1920.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

The forces during the battle for Warsaw were approximately equal — more than 100 thousand soldiers on each side, including 14 thousand soldiers of the UNR Army. But the Bolsheviks had an advantage in cavalry, which ensured their mobility. The first stage of the battle began on August 12 in the area of the town of Radzymin, about 30 kilometers from Warsaw. Over the next few days, the Red Army, albeit with heavy fighting, gradually advanced. The counterattack of Polish units on August 15-16 under the command of Pilsudski himself was decisive. They hit the flank of the Bolshevik forces of the Western Front. The Red Army could not seize the initiative and by the end of the month was forced to retreat with heavy losses. The victory at Warsaw went down in Polish history under the name "Miracle on the Vistula". This phrase was spread by Pilsudskiʼs political opponents in order to downplay his merits as a commander and attribute his success almost to divine providence.

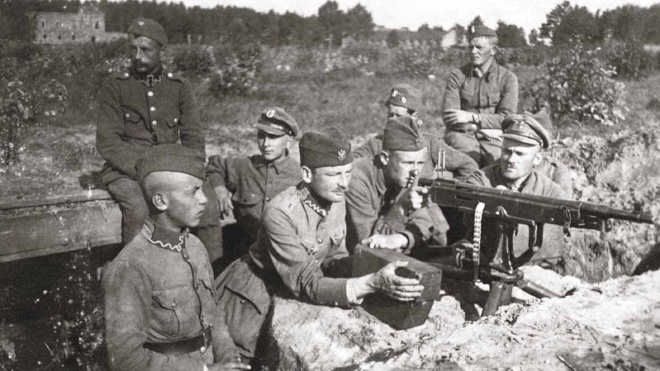

The Red Cavalry on the Polish Front, 1920. Polish machine gunners during the Battle of Warsaw, August 1920. Symon Petlyura (far right) with Colonel Mark Bezruchka (second left) and other officers of the Army of the Ukrainian Peopleʼs Republic, 1920.

Getty Images / «Babel'»; Wikimedia / «Бабель»

The troops of the Ukrainian Peopleʼs Republic successfully operated in other areas of the front. For example, they did not allow the Bolsheviks to break through the Dniester line to block the supply of military goods from Romania to Poland. At the end of August 1920, the Ukrainian units under the command of Colonel Mark Bezruchko stopped Budyonnyʼs First Cavalry Army near Zamostia, which was moving to help Tukhachevsky near Warsaw. During September and October, the Polish-Ukrainian troops launched a counteroffensive and pushed the Red Army behind Zbruch. Petliura hoped to liberate as much of the Right Bank Ukraine from the enemy as possible, until the enemy had time to recover. But already at the beginning of November, the Poles stopped hostilities and started negotiations with the Bolsheviks.

Captured Red Army soldiers after the defeat in the Battle of Warsaw, 1920.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Poland sacrificed Ukrainian allies in negotiations with the Bolsheviks. Immediately after the victory in the battle for Warsaw, Pilsudski passionately said: "On behalf of Poland, I call: Long live a free Ukraine!" But he quickly resorted to political pragmatism. He understood that Poland could not withstand a protracted war with the Bolsheviks. So it was worth bargaining for better conditions for itself until the situation changed. In addition, there was a large parliamentary opposition on the Pilsudsky Tisza, which demanded "an end to the Ukrainian adventure."

In the end, representatives of the Ukrainian Peopleʼs Republic were not invited to the Polish-Soviet talks in Riga at all. Some of the legal nuances of the Warsaw Pact, which Ukrainian government official Serhii Shelukhin warned about, came into play here. In the text of the treaty, the Poles recognized independence and undertook not to enter into agreements against Ukraine, and not specifically against the government of the Ukrainian Peopleʼs Republic. According to the Bolsheviks, "independent Ukraine" was to be represented at the negotiations in Riga by the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. And the Poles agreed to this, which surprised the head of the Soviet delegation, Adolf Joffe. In March 1921, the parties signed the Riga Peace Agreement, dividing the Ukrainian lands along the Zbruch River between them.

Footage of the arrival of the Polish and Soviet delegations for negotiations in Riga, as well as the ceremonial parade in Warsaw after the victory over the Bolsheviks, 1920.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

The UNR army was left without allies and almost without weapons. The mass popular anti-Bolshevik uprising that Petlyura had hoped for did not happen on Ukrainian lands. He was never forgiven for the Warsaw Pact. And Soviet propaganda also tried, telling how "Petlyura sold Ukraine to the Polish lords." At the end of November 1920, under the pressure of the Red Army, almost 30,000 Ukrainian soldiers crossed Zbruch and were sent to Polish internment camps. Later, the government of the Ukrainian Peopleʼs Republic also moved to Warsaw in emigration. And Poland received a respite from Soviet aggression until the beginning of the Second World War in 1939.

Translated from Ukrainian by Anton Semyzhenko.

You can become real allies of independent journalists and support Babel: 🔸 in hryvnia, 🔸 in cryptocurrency, 🔸 Patreon, 🔸 PayPal: [email protected].