Censorship in the media

With the beginning of the First World War, censorship was introduced in all European participating countries. Censorship departments were created in military structures, various ministries, and even in local self-government bodies. In Germany, Austria, and Russia, the censors were mostly military officers, and in Britain, France, and Italy, they were mostly civilians.

First of all, the censorship took care of the press. The first restrictions were quite adequate and related to military secrecy: the number of weapons, the number of armies, movements and military operations, the characteristics of fortifications. But very soon materials criticizing the government and the command, reports on strikes, demonstrations, and problems with supplies were censored. Strict restrictions were justified by the fact that such information could cause anxiety and worry in society and undermine its morale. Censorship wording appeared, such as “defeatist sentiments,” to which calls for peace were equated. And in France, an unspoken ban on the word “peace” in articles was introduced.

Prohibited books, newspapers, pamphlets and other printed matter in a British Censor Office, 1914.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Already in the second year of the war, the European press received numerous censorship instructions. There were more than a thousand of them in France, and about two thousand in Germany. In order to “facilitate” the work of journalists, the authorities issued special “censorship books” with a list of restrictions. But over time, the instructions became more blurred, and something forbidden could be found in any article.

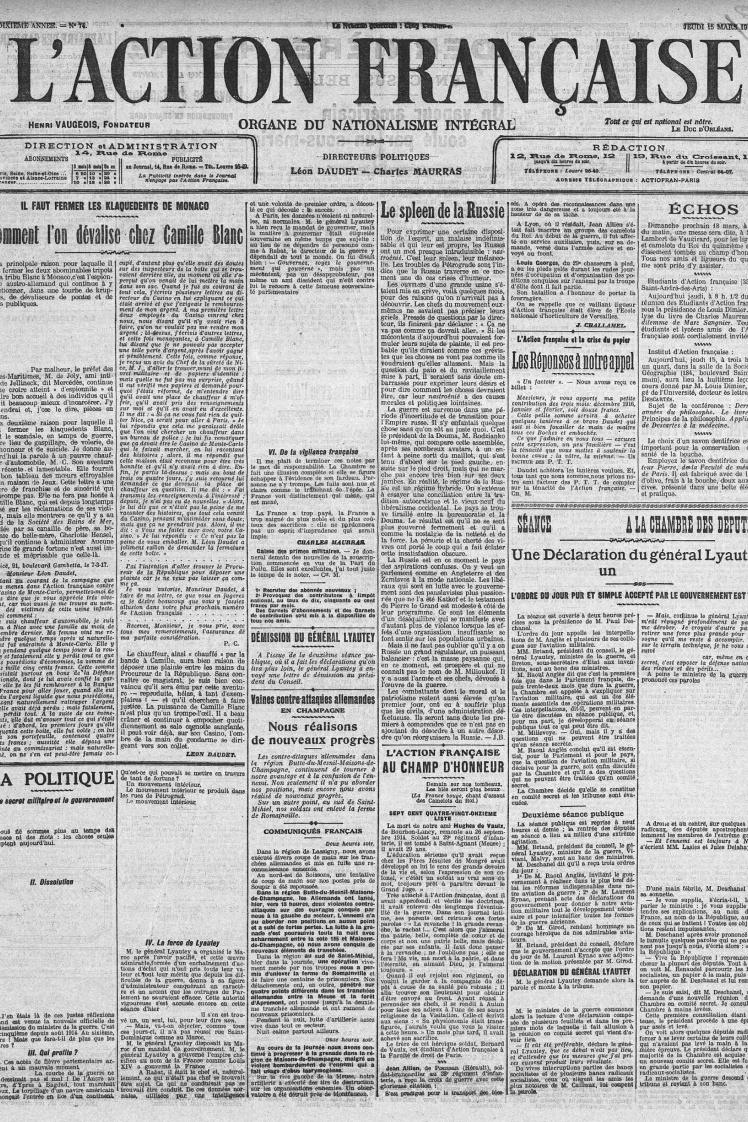

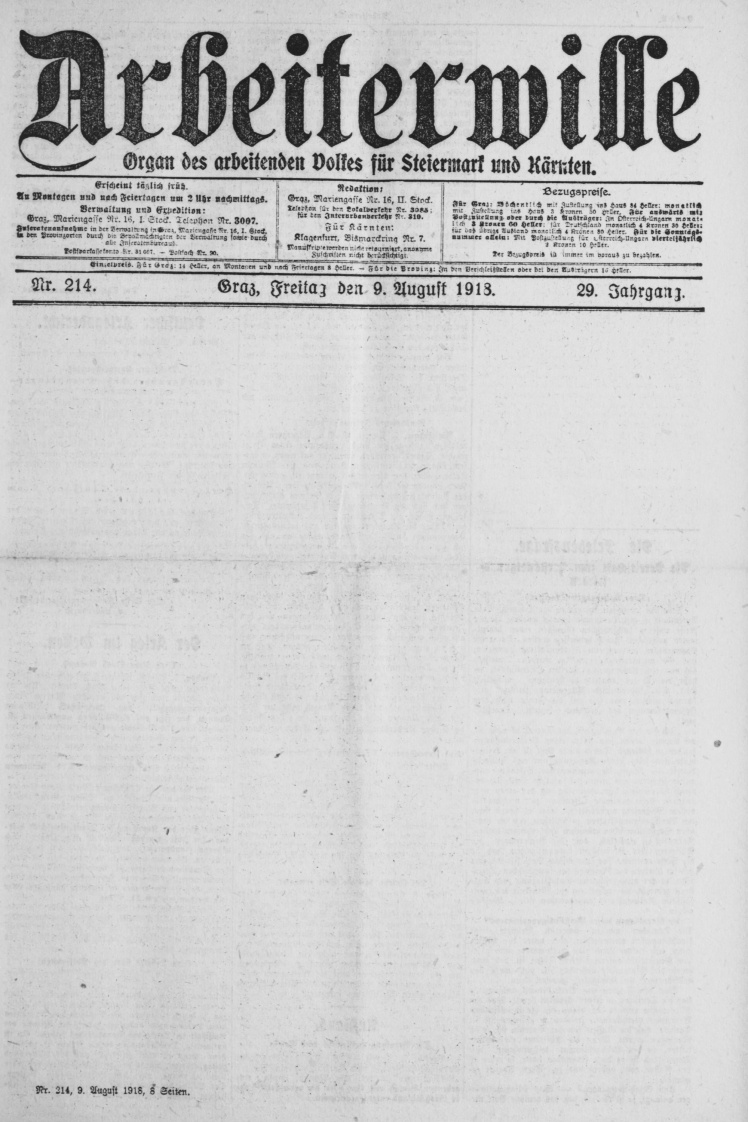

The strictest censorship was in France, Italy, and Austria. Almost all printed articles were pre-checked. Censors noted questionable lines or even whole passages that had to be removed from print. Because of this, newspapers in these countries often came out with white spots. There were also cases when nothing remained of the article except the title or the authorʼs last name.

Censored issue of the French newspaper LʼAction Française for March 15, 1917. Censored issue of the Austrian newspaper Arbeiterwille for August 9, 1918.

gallica.bnf.fr / «Бабель»; anno.onb.ac.at / «Бабель»

For a violation, the newspaper could be closed for a period of several days to six months. And for repeated violations the punishment was closing of the newspaper, banning journalists from writing, fine or even sentence to prison. Because of this, the intimidated editors plunged into complete self-censorship and, to be safe, sent the articles to the censors voluntarily for additional verification. But this didnʼt help either: the censor could initially pass the article, and after publication, find something “dubious” in it.

The fate of the French newspaper Le bonnet rouge and its socialist editor Miguel Almereyda was the worst. In July 1917, the newspaper was closed on the suspicion that it was financed by the Germans. Almereyda was arrested, and a month later he was found in a cell hanging by shoelaces. And although almost no one believed in the version of suicide, the case was closed. German pastor Johannes Lepsius was more fortunate. He was only forced to leave the country for publications about the repression of Armenians by Germanyʼs ally, the Ottoman Empire.

Censorship also prevented war correspondents from working. With the beginning of the war, the British government banned reporters from going to the front. Then two correspondents, Philip Gibbs of the Daily Chronicle and Basil Clarke of the Daily Mail, went to the front line illegally, at their own peril. After several articles, the journalists were caught and sent home, threatening to be shot if they returned. In a few months, the government allowed five correspondents to be accredited to the front. But they worked under the strict supervision of escort officers. Similar rules have been introduced in other countries. Articles from the front line were first checked by the military, then by national censorship bodies, and then proofread by editors.

Demonstration tour of the trenches for journalists, organized by order of the Supreme Military Council of the Allies, 1916.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Sometimes it reached the point of absurdity: journalists were required to tell about the soldierʼs exploits, but were forbidden to mention specific military victories. It was, of course, forbidden to write about defeats or the harsh conditions of trench life. In the case of the “Spanish flu”, this led to tragic consequences on a global scale. In the countries participating in the war, reports about mass diseases on the front lines were not passed by censorship, so that the soldiers did not lose their fighting spirit. In the end, the “Spanish flu” epidemic turned into the most massive pandemic in human history, from which 50 to 100 million died.

Surprisingly, in tsarist Russia, censorship during the war was not so strict. Initially, only articles related to military secrets were subject to the ban. Thanks to this, extremely critical articles on political topics were published in the press. When the Minister of Defense Alexey Polivanov was reprimanded for this, he just threw up his hands and said that his censor officers were acting according to instructions and were not involved in politics. Since 1916, the authorities tried to extend censorship to political articles and even to the speeches of Duma deputies. However, it was not possible to suppress dissatisfaction with the authorities. The political crisis, which began even after the lost “small victorious war” with Japan in 1905, only grew.

However, strong pressure on the press forced it to learn how to circumvent numerous bans. For example, in France, some newspapers collected for their subscribers special editions with previously censored texts, but no longer edited. Others published two versions of the issue: with edits, which were sent to the censors for report, and without edits, which went on sale. On the one hand, publishers took risks. On the other hand, the censors could also be caught for lack of vigilance, so they often turned a blind eye to it.

French soldiers near a newsstand near the Western Front, September 6, 1917.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

In Germany, a more subtle approach was practiced — the authors wrote about obvious things in a veiled way with the help of historical parallels. The editor of the weekly Die Welt am Montag, Helmut von Gerlach, was quite successful in this. He could not openly criticize the aggressive policy of the military leadership. So he wrote articles in which he condemned the French emperor Napoleon. At the beginning of the 19th century, he captured half of Europe, but suffered a crushing defeat and went into exile. At the same time, the editor praised the national hero of Germany, Otto von Bismarck, who, defeating Austria in 1866, didnʼt demand any Austrian territories, but concentrated on uniting the German lands into the first federal German state. Censors, of course, understood the hints, but could do nothing.

Censorship in correspondence, theater, cinema, and thoughts

After the success of the media, the censors took on the mail. First, postal control was introduced in all the armies of the countries participating in the war. In addition to monitoring the observance of military secrecy, attention was paid to complaints about food shortages, illness, and war fatigue. The censors were mostly army officers, who either crossed out "undesirable" phrases or paragraphs, or simply discarded soldiersʼ letters. In Italy, Germany and Austria, the soldiers could be brought to a tribunal for "subversive false information" in correspondence.

Headquarters of the British Postal Censorship Department in Liverpool, 1917-1918.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

In some countries, postal censorship went even further and took up correspondence between civilians. In Britain, all mail was controlled by special censor departments. In 1918, about five thousand censors worked there. Special attention was paid to letters sent abroad, primarily to neutral countries. In France, only the mail of certain "unfortunate" people was controlled, as well as, just in case, all members of parliament.

Later, films, theater plays, and even circus performances came under censorship. First of all, the works of authors from enemy countries were banned. The plays had to be edited so that there were no plots about adultery, scenes with a hint of sex, vulgar and abusive expressions. It was forbidden to make fun of the military and policemen, and the characters of "criminals" and "whores" were deleted from the plots of the plays. In 1915, the Berlin Theater Police monitored 1,321 performances and found 773 violations. The directors then quipped that "the policeman was the most attentive spectator." In Paris, the Special Commission at the Prefecture of Police censored more than 4,500 performances. France also had one of the harshest film censors. In 1916, 145 films were banned here, and in the following year — already 198.

A performance banned by police censorship at the Renaissance Theater in Paris, 1914-1918.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Later, censorship also reached private conversations. In Britain, people could be fined or imprisoned for "unsavory" speeches at conferences, for example, for calls for peace talks. And in Italy, agents of the Servizio P, created in January 1918, that is, the Propaganda Service, eavesdropped on the conversations of workers and soldiers, identified those who were dissatisfied and reported them to the authorities.

Censorship in the USA

The United States entered the First World War only in April 1917, but censorship was introduced almost from the first days of the war. American censors quickly began to cooperate with the British and established a multi-stage check of all letters and telegrams sent from Europe to the United States. The US Navy even stopped ships of neutral nations to inspect the mail and newspapers they were carrying. Sometimes passengers and crew were searched.

After sending its troops overseas, the US imposed strict controls on soldiersʼ correspondence. All letters, without exception, were checked first by the company censor, then by the regimental censor, and then by the chief censor of the military base. Soldiers who were going home on leave were also checked, so that they did not pass on letters from comrades in the service bypassing official channels.

War correspondents also had problems. All journalists who accompanied American troops to Europe had to swear not to publish any information "useful to the enemy and harmful to the country." Anything could fall under this definition. In addition, the newsrooms had to deposit a ten thousand dollar security deposit for each of their war correspondents in case he broke the oath.

American photographers take pictures with the permission of military censors, July 26, 1917.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

In 1917, the US passed the Espionage Act, followed by an even stricter Subversion Act. They allowed condemnation not only for actions, but for critical statements about the government and military deeds. Appeals for peace, for example, were subject to the law because they could be considered as "obstructing the recruiting service" or "harming the distribution of war bonds."

The authorities urged Americans to identify internal enemies. Thus, a real witch hunt began in the USA for pacifists, socialists who opposed the war, and especially for "German spies." Groups of "volunteer detectives" were created across the country. Just one such organization, the American Defense League, had more than 250,000 members in 600 cities across the country.

Children in front of an anti-German poster at the entrance to Edison Park in Chicago, 1917.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

German immigrants and Americans with German roots were especially unlucky. One could be arrested for a German sign or even for speaking German. Once a "detective" overheard his neighbor speaking German to his parrot and reported him. The man was arrested, and the parrot was sent to a pet store. And this German was still lucky. Sometimes such "spies" were tarred and feathered, and some were even lynched.

Censorship and politics

And, of course, censorship helped politicians win elections and eliminate competitors. David Lloyd George began the First World War as the Minister of Finance of Great Britain. Subsequently, he received the specially created position of Minister of Munitions, then became the State Secretary for War Affairs, that is, the head of the Military Department. And in December 1916, he replaced Henry Asquith as prime minister.

Last but not least, Lloyd George owed his successful career to the British media magnate Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe. He owned The Times, Daily Mail and other smaller newspapers, and in total controlled more than 40 percent of the circulation in Britain. In fact, it was the Northcliffe papers that first advocated the creation of the post of Minister of Munitions, which was filled by Lloyd George, and later criticized Asquith, destroying his public rating. A grateful Lloyd George offered Northcliffe a ministerial portfolio in his office. But the latter refused in favor of a more profitable position for himself as the director of the propaganda department.

Lord Northcliffe driving a 1908 Mercedes. Northcliffe was the first owner of cars of this brand in Britain.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

At the beginning of the First World War, the former French Prime Minister, journalist and publisher Georges Clemenceau was one of the fiercest critics of censorship in the media. Once, as a sign of protest, he even renamed one of his newspapers Lʼhomme libre (The Free Man) to Lʼhomme enchaîné (The Chained Man). But once again leading the government in November 1917, Clemenceau declared that "only a complete idiot would abolish censorship." Moreover, he actively used censorship against his political enemies, especially those who advocated peace. In addition, he ordered defamatory articles and persecuted newspapers that tried to criticize him.

Georges Clemenceau among soldiers on the front line in northern France, 1914.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

At the end of 1916, the head of the German government, Reich Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg Theobald, took the initiative for peace negotiations against the background of the difficult situation on the front lines. In response, the military elite, which controlled censorship, launched a propaganda campaign under the slogan "Down with this chancellor." And in six months Theobald was forced to resign.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the leader of the Socialist Party of America, Eugene Debs, became popular due to his oratorical talent. Although he did not win the presidential elections of 1912, he received about a million votes. During World War I, Debs opposed US involvement in the war. After one of the pacifist speeches in 1918, Debs was arrested under the Subversive Act and sentenced to ten years. In the 1920 elections, he ran from prison and took third place. At the end of the same year, the law on subversive activities was repealed. And in 1921, the victorious president, Woodrow Wilson, pardoned Debs along with others convicted under this law. But the witch hunt unleashed by the American government did not subside for a long time, and Debs was never able to get rid of the "enemy of the people" image.

Eugene Debs gives an anti-war speech after which he is arrested under the Subversive Act, 1918.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Translated from Ukrainian by Anton Semyzhenko.

Total censorship has never benefited anyone. Just look at our aggressor neighbor. So support Ukrainian independent journalism: 🔸 in hryvnia 🔸 in cryptocurrency 🔸 via Patreon 🔸 or PayPal: [email protected].