At 7:58 a.m., Mykhailo Fedorov enters his reception room. He is wearing a cap by Stone Island, a company now popular in the Ukrainian government, and a sweatshirt by the well-known Balenciaga brand.

“You are fashionable!” I say, shaking hands with the minister.

In fact, the sweatshirt is not just a fashionable item, Balenciaga created it in support of Ukraine. All money from sales through the UNITED24 platform goes to rebuilding Ukraine. The retail price is €250, or almost 10 thousand hryvnias.

Fedorovʼs office.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

Together with Fedorov and the photographer, we go to the ministerʼs office. Last time we were here on February 3rd. Since then, almost nothing has changed: there are chess pieces on the desktop, drawings of Fedorovʼs 5-year-old daughter and the illuminated inscription “Diy” (”Act” in Ukrainian) in the closet. Previously, there was a photo of the Italian football coach Claudio Ranieri on the wall, whom Fedorov admires. Under the leadership of the Italian, the English club Leicester became the champion of England for the first time in its history, and did it without star footballers.

“One of the deputies took the photo from me,” laughs Fedorov.

Among the new items in the cabinet is a box of wine from the GoodWine store. This wine survived the March 3 Russian airstrike on the companyʼs warehouse in the Kyiv region. Later, the store sold it, and 20 hryvnias from each bottle went to the Ukrainian army. Fedorov gives this wine to Western partners.

That wine from GoodWine.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

In the morning we have an hour to chat. Fedorov asks his assistant to bring black coffee. I ask if he always comes to work so early, or if this is a one-time event for us.

“I never arrive later than eight in the morning. There is a Zoom call at 07:30, I finish it in the car, and then I go up [to the office] for the next meeting,” says Fedorov.

He comes from Vasylivka, Zaporizhzhia region, which is currently occupied. He graduated from the university in Zaporizhzhia, which is now under daily shelling by the Russians. I ask how the war affected him personally.

“I try to remain calm and balanced and not to switch to emotions and reflections, because this greatly hinders effective action. We will definitely de-occupy Vasylivka and Melitopol — itʼs a matter of time,” says Fedorov confidently.

On the twenty-fourth of February, his relatives were in Vasylivka, but later they all left, except for his father: he wanted to go to war, but a stroke didnʼt let him do it. The ambulance took him to occupied Melitopol. Mykhailo managed to take him from there in only two months, in a difficult condition.

“My uncle was also kidnapped and later freed, they [the occupiers] didnʼt fully understand [who he is]. We also took him out.”

I ask if he believed in the possibility of a full-scale invasion. Fedorov grimaces a little and admits that he does not like to answer this question.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

“Itʼs as if...”

“Kicking empty air after a fight?” I suggest.

“Exactly! I will say only one thing: on February 16, the deputies passed a law that allowed all important data about our infrastructure to be hosted abroad. It was a reaction to a possible problem.”

Fedorovʼs ministry does not look like a traditional one. There is a formal structure — departments, expert groups, but in practice these are teams working on projects. A total of 200 employees and 25 developers. Until February 24, there were four directions: putting public services online, development of the Internet, digital literacy and digital economy. Now military technology has been added. Currently, the ministry is preparing a presentation Ministry of Digital 2.0 to tell more about the new direction.

Because of the war, the tasks of the teams also changed. Those who were responsible for digital services now focus on quick payments of compensation to victims, damaged property, eVorog chatbot, electronic documents, Diia.Radio and Diia.TV. The team that was responsible for the development of the Internet is now engaged in its restoration in the de-occupied territories and working with Starlink terminals. The Diia.City project team is negotiating with technology companies about their exit from the Russian market and cooperation.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

Another new goal, which was actually relevant even before the war, is that Fedorov wants to digitize 100% of state services and make it so that where there should be no state, it did not exist. According to his calculations, this means minus 50-70 thousand officials and minus 4-5 ministries.

“At the beginning of the war, about 25% of people worked [in the Cabinet of Ministers], and nothing was broken, everything was resolved quickly,” recalls Fedorov.

Eventually, the rules became more important than the fear of losing everything, and each decision began to be discussed longer. How to make ministries more flexible and adaptable to new conditions is an open question. The Ministry of Digital Transformation developed a template for the self-audit of ministries, which was completed at the end of August. Heads of departments are now presenting their ideas for changes to Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal and a small team.

“They come charged, propose a new organizational structure — what to remove, what to optimize, where and which people to transfer, what reform to make. Letʼs see how it will be implemented after pitching,” says Fedorov.

Sometimes it seems that he has a perfect model of an ideal world in his head — and it will never work like that.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

At nine oʼclock in the morning, Fedorovʼs first meeting is with Valeriya Ionan, his deputy, responsible for European integration. Meetings here are called “personals”. All of them follow a similar scheme: in the evening, the participants send a presentation to Fedorovʼs assistant, otherwise they are not allowed to see the minister. Fedorov explains: this is not because he likes beautiful pictures, but to better structure his thoughts. After the meeting, the participants receive a follow-up.

Ionan enters the office without knocking and with a smile.

“You broke in!” Fedorov laughs.

He sits down in the center of the table and turns to the monitor to his left.

Ionan turns on the presentation and talks about new products on the "Diia. Digital Education" platform, where there are currently many online courses. Soon, with the help of educational series and online lessons, people will be able to take various courses there, receive a certificate and immediately apply for vacancies in their region. Partnership negotiations with the largest job search portals have already been held.

Mykhailo Fedorov and his deputy Valeria Ionan.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

“[Minister of the Economy] Yulia Svyrydenko is strongly ʼpushingʼ government vacancies,” Fedorov notes, implying that such options will also be available on the portal.

Ionan explains how it should work. There are 200 educational series on the platform. A person chooses a direction, takes relevant test, the program determines the level of training and creates a program from various educational series.

“We havenʼt seen this on other educational platforms,” she convinces.

There will also be courses in English on the platform, and later in the app, as well as a test on the level of its knowledge. Fedorov admits that the Ministry of Digital Transformation is engaged in a secret project: they want to introduce English as a full-fledged second language in Ukraine, but not as a state language — rather for business communication. This is a task from the president. Fedorov does not reveal the details of the project, but itʼs planned to be launched next year. The goal is pragmatic: the Ministry of Digital Transformation analyzed countries that prioritized learning English — all showed GDP growth. Fedorov himself had weak English at school and university, now he has to practice it every day. But he admits that he neglects homework, so the process is delayed.

For a few minutes, the minister and his deputy talk about the Diia.Business portal, where private entrepreneurs can get business advice. The problem is that the portal has grown, there are many services, and users are getting lost. The ministry plans to redesign and restructure the platform and translate it into English. On May 17th, the Diia.Business center was opened in Warsaw. There are still requests to open such centers in Wroclaw, Krakow and Gdańsk in Poland, but itʼs too early.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

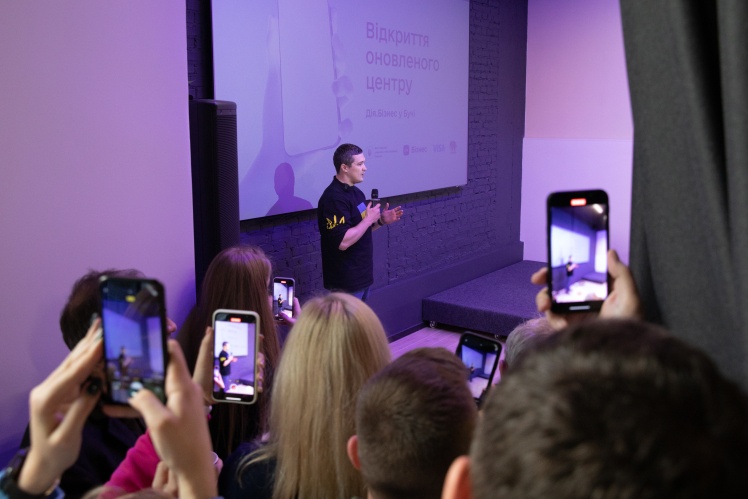

After the meeting with the representative, Fedorov puts on a jacket and a cap, and we, accompanied by the ministryʼs press secretary, a photographer and a camera operator, go to the opening of the Diia.Business center in Bucha in a Mercedes minibus. It was launched in December 2021, and at that time it was considered a benchmark. There, entrepreneurs could learn, look for partners and investors. After the Russian invasion, the center, like the entire Continent residential quarter where it is located, was occupied and destroyed. Currently, the center has been restarted with the support of Visa and Caparol Ukraine. Now there are even more services: support for local entrepreneurs, consultations on local business development, relocation of enterprises from the eastern regions, psychological support for the residents, educational courses for teenagers.

On the road, we donʼt talk about plans and achievements, but about problems. For example, Diia.Business has already been restored in Bucha, but many people in the city still donʼt even have new windows. There is a certain dissonance in this, because applications for compensation for property damaged by the occupiers are sent to the Diia app. Of course, Fedorov knows about this problem, but he canʼt solve it. All applications are entered into a special register. Next, the deputies in the second reading have to adopt the draft law, which will determine the further fate of the applications.

“We are ʼpushingʼ other ministries and institutions, because people donʼt understand: they left an application, and whatʼs next? I also feel a certain responsibility,” says Fedorov.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

He says that money for reconstruction is also collected through the UNITED24 platform. More than 400 million hryvnias have already been collected. The ministry offered to use these funds to renovate high-rise buildings. So far, 15-20 houses have been selected, which means approximately 4,000 people who will be able to return to their homes.

Another problem directly facing Fedorovʼs ministry is the outflow of clients from Ukrainian IT companies. Because of the war, international customers are afraid to cooperate with Ukrainians. Fedorov says that there is such a problem, but the numbers are still optimistic. In the first half of the year, the Ukrainian IT market grew by 23%.

Another thing is the foreign business trips of IT specialists. Back in June, Fedorovʼs deputy Oleksandr Bornyakov said that conscripted IT industry workers may be allowed to travel abroad for a certain period. The government should have taken the appropriate decision, but it has not yet done so.

“We are waiting for the signing,” says Fedorov.

He admits that because of this delay, he himself stopped going on business trips abroad — he is uncomfortable to do this.

We reach the renovated Diia.Business center around 11 in the morning. I ask Fedorov whether he was in Bucha after the deoccupation. He doesnʼt remember — after February 24, many events got mixed up.

At the central entrance to the residential quarter, where Diia.Business is located on the first floor, Fedorov is already met by the mayor of Bucha, Anatoliy Fedoruk, and the head of Kyiv regional administration Oleksiy Kuleba. Nearby are destroyed houses, a playground, some windows in high-rise buildings are covered with plywood, some with film, a little further away, the sounds of repairs can be heard.

To the right of Fedorov, the mayor of Bucha, Anatoliy Fedoruk, and the head of Kyiv region Oleksiy Kuleba.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

Fedorov greets everyone and goes inside, where a lot of people — businessmen, local officials — have already gathered. There is fresh coffee, and a small stand with products from local businesses. For example, cotton flowers dyed in different colors. The organizers take Fedorov to a small room on the second floor. There they explain how and what will happen: first his speech, then of Fedoruk and Kuleba. Fedorov takes off his jacket and cap. His press secretary suggests that the hair got squashed a little on the sides.

“Well, donʼt you scold my cap,” he laughs, straightening his hair, “I like it, itʼs a gift from my wife.”

He asks the organizers what the key message of his speech should be. Fedorov is asked to speak about the restoration of Ukraine, despite the war. This is what he is talking about. The presentation lasts forty minutes, after which the minister has a short appearance on the air of the national telethon and a short interview for the Japanese media The Yomiuri Shimbun. The journalist asks Fedorov about The Army of Drones project.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

“This is President Zelenskyʼs idea. Large international organizations donʼt always understand the needs of Ukrainians and often spend large amounts of money irrationally. The idea of UNITED24 is to allocate money to priority needs, in particular to The Army of Drones,” says Fedorov.

Finally, he gives a short press conference, takes photos with businessmen, collects business cards and hurries to the next location — the test site, where the Global Drone Academy school trains aspiring drone operators. The minister is treated to macarons from local entrepreneurs and coffee. Suddenly, two women appear behind him and ask where he bought such a sweatshirt. Fedorov offers to scan the code on his back. It doesnʼt work the first time. The women thank us, and we get into the car.

“I wonʼt eat it, I wonʼt eat it, I wonʼt eat it, I have the willpower,” repeats Fedorov, looking at the cake, and then quickly eats it.

Fedorov is asked how to buy a Balenciaga hoodie.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

Already on the way, Fedorov found out that Bucha Mayor Fedoruk hadnʼt sent an application for high-rise buildings that can be restored via UNITED24. Why he didnʼt do this is a mystery to the minister.

We are approaching the polygon. Several dozen military personnel are trained here. Such centers operate throughout the country. On average, the course lasts 7 days. In total, the organizers plan to train more than 2,000 drone operators. More than a thousand drones worth more than 2 billion hryvnias have already been contracted. The Ministry of Digital Transformation has calculated that approximately 10,000 small drones and 250 long-range drones are needed to secure the entire front line.

Fedorov is met by the head of the Global Drone Academy Anton Viklenko and several students. They tell the minister how everything is arranged, that three more drones are needed for the school. Fedorov listens and writes everything down in the phone.

“The most difficult thing is the topography. A person operates the drone, you tell him: “to the northeast” — and he doesnʼt know where it is. Unfortunately, not everyone can pass the exam,” says the head of the school.

Head of Global Drone Academy Anton Viklenko.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

Fedorov promises to continue supporting the school. In the end, he is allowed to play with one of the drones and conditionally scout the situation near the dummy howitzers. The military man who gave Fedorov his drone takes the opportunity to say that he needs one more drone, or better two. Everyone laughs.

Suddenly, the actor, host and humorist Ihor Lastochkin appears at the training ground. He is unrecognizable: he has grown a mustache, his face is covered by a cap. He came to pass the exam before he is mobilized. We talk a little with him. He says that at one time his former friends from Moscow gave him a Phantom drone for his birthday, which he hardly used, and in 2014 he gave it to Donbas.

One of the military who is learning how to fly drones.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

“These are [courses] to eliminate illiteracy, to know how a combat task, intelligence is planned. So I will already have some kind of specialty, and if necessary, I will be able to go [to the front],” says Lastochkin. Now all his TV projects are on hold.

Finally, Fedorov takes a picture with the military, and we return back to the ministry. The minister explains that such trips are necessary in order to understand how everything works. Usually everything is agreed with the General Staff of the Ukrainian army, and this is how the drones get to those who need them.

Global Drone Academy head Anton Viklenko (left of Fedorov) and humorist Ihor Lastochkin (right).

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

“But we want to start an IT system that will record that such and such a fighter has undergone training here, performs like this, and here are his or her results with the drone. Then we will understand which school teaches at which level. In order to build a database and effectively make managerial decisions about who to help and who not,” says Fedorov.

I ask if there will be IT solutions for the military, because there are many difficulties, even with obtaining certificates. Fedorov knows about the problems and promises to solve them. He says that now the ministry is working on mortgages for the military, then for doctors, and after that for teachers.

“So imagine, you want to buy an apartment with a mortgage, you go to Diia, click “get a mortgage” — and your application to the bank is formed, and you can have several. After that, they send you a reply about terms and interest. And there are no calls, humiliations, questions about how much you earn. I think we will launch it at the end of October, and it will be a technological revolution for us,” he says.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

I ask whether the authorities plan to send out summonses via Diia or use it for the registration of the military, which was previously rumored. In September, the Ministry of Digital Transformation said that they were not developing such a service. Fedorov says that even now there are no such plans. He talks a little about his vision of the army: the Ukrainian Armed Forces should be approached more systematically — transparently answering the question of what the army is, how to get to it, and exactly where, what the tasks are.

“After all, for people, the army is mostly about the fact that I will now be “at the front” and they will shoot at me there, and if you explain to them what is what, and properly package the army as a product — wat structure does it have, whom it needs, how mobilization and training are conducted, when you can get to the front, etc. And then people will responsibly register, understand and know their rights. We proposed this vision to the Ministry of Defense, and I hope that we can implement it. I think it will be cool,” he says.

Fedorov prefers not to tell in detail what exactly the Ministry of Digital Transformation is helping the Ministry of Defense and the Armed Forces of Ukraine with, but one thing is on the surface — itʼs Starlink terminals. Fedorov wanted to receive them since the creation of the ministry. He says that he was told by all regulators, departments and specialized bodies that the terminals will not work in Ukraine — they are expensive, use wrong transmission channel, this communication is bad, etc. Fedorov sent letters to Elon Muskʼs SpaceX, but no one answered him. In the end, the ambassador of Ukraine to the USA, Oksana Markarova, managed to contact the minister with the management of the company. Three days before the full-scale invasion, Fedorov convinced them to enter Ukraine.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

“I assured them that they would receive a license in record time. ʼI will be your nanny, father, and mother, and I will personally check everything, just come inʼ,” recalls Fedorov.

On the twenty-sixth of February, he wrote a tweet asking Musk to provide Starlink, to which the businessman replied that they were already on their way.

“After that, they opened Ukraine as geolocation without a license, without anything. We gave everything later and started receiving Starlink terminals from the European Union and international partners,” says Fedorov.

Around 3:30 p.m., we return to the ministry, where two more meetings are scheduled — actually more then two, but some of them are closed for us. One of them concerns the automation of excise stamp processes in order to improve analytics, and the consumer could scan the stamp and understand how a particular bottle of alcohol got to Ukraine. We are asked not to photograph the slides and participants of the meeting, as well as not to write who was at it — not everyone agreed to this. So we mostly listen to arguments. The essence of the meeting is to find a software solution to prevent counterfeiting of excise stamps. And synchronize everything with tax databases, including old-style stamps. One of the persons present at the meeting is one of Fedorovʼs advisers, Giorgii Tshakaya, who headed the Tax and Customs Service in Georgia under Mikheil Saakashvili, and then helped with the reform of the Odessa Customs. He argues the most. At one point, Fedorov asks how it works in Georgia. He answers simply: “If a counterfeit is imported into Georgia, they take away the car in which they found some duty-free goods.”

“We have a democratic country,” Fedorov jokes with him.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

“We have it too, itʼs just that the rules work correctly,” he retorts.

“Thatʼs all, we part ways,” laughs Fedorov. They agree to meet again to think about the software.

This meeting lasted a little over an hour, the next one was with team leaders, HR and the head of the mobile development team at Diia Yevhen Gorbachev. Almost all of them are wearing branded Diia sweatshirts, some people are connecting via video. Fedorov says that he is worried that in the last projects that were made, they often return to old mistakes, there are many revisions with texts and designs. And this should be quickly corrected by simply introducing clear rules. In addition, such a number of projects and work has accumulated that he does not have time to monitor what is happening in real time. This will be corrected through a new structure and platform where tasks and progress can be viewed in real time. After the meeting, Fedorov explains why.

“The head of developers sells the idea of transformation himself. He doesnʼt say this, but he understands that they work like crap, they can work better, some functions are missing. They have to develop themselves, understand the problems, dig and believe that they are doing it themselves,” Fedorov laughs.

Meeting in Mykhailo Fedorovʼs office.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

He is a supporter of a soft management system.

“There is no such thing as that I get angry or say: ʼGod, you promised to do it!ʼ People try to make a result on their own, and they have the motivation to do it,” he says.

The Ministry of Digital Transformation has an HR team that deals with people. According to Fedorov, people who donʼt fit the values simply do not get into the ministry, and staff turnover is only 2% per year. Fedorov is helped by HR staff who see who may soon burn out and who may have a conflict.

“The HR team is my salvation, I canʼt imagine what it would be like there, because these are all people and all people are ambitious and talented. And itʼs not easy with them,” says Fedorov.

We say goodbye. He still remains in the ministry building, and photographer Oleksandr Kuzmin and I go down the empty, closed government quarter.

“You know, this is some kind of ministry of a healthy person, I didnʼt want to leave,” Oleksandr tells me.

Meeting on automation of excise stamp processes.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

Translated from Ukrainian by Anton Semyzhenko.

Your donations help Babel to act: help via Patreon 🔸 [email protected]🔸donate in cryptocurrency🔸in Ukrainian hryvnia.