Chechnya and the rest of the North Caucasus

In June 1991, the independent Chechen Republic of Ichkeria appeared on the territory of the former Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. It actually existed until 2000. In November, the Chechen Republic, relying on the USSR laws and constitution, withdrew from the Soviet Union and declared independence. In March 1992, the Chechen Republic adopted the constitution. Then the Republic refused to sign the Treaty of Federation with Moscow. Instead, it signed an intergovernmental agreement on the complete withdrawal of Russian (former Soviet) troops from its territory. And in early July, the last Russian soldier left Chechnya.

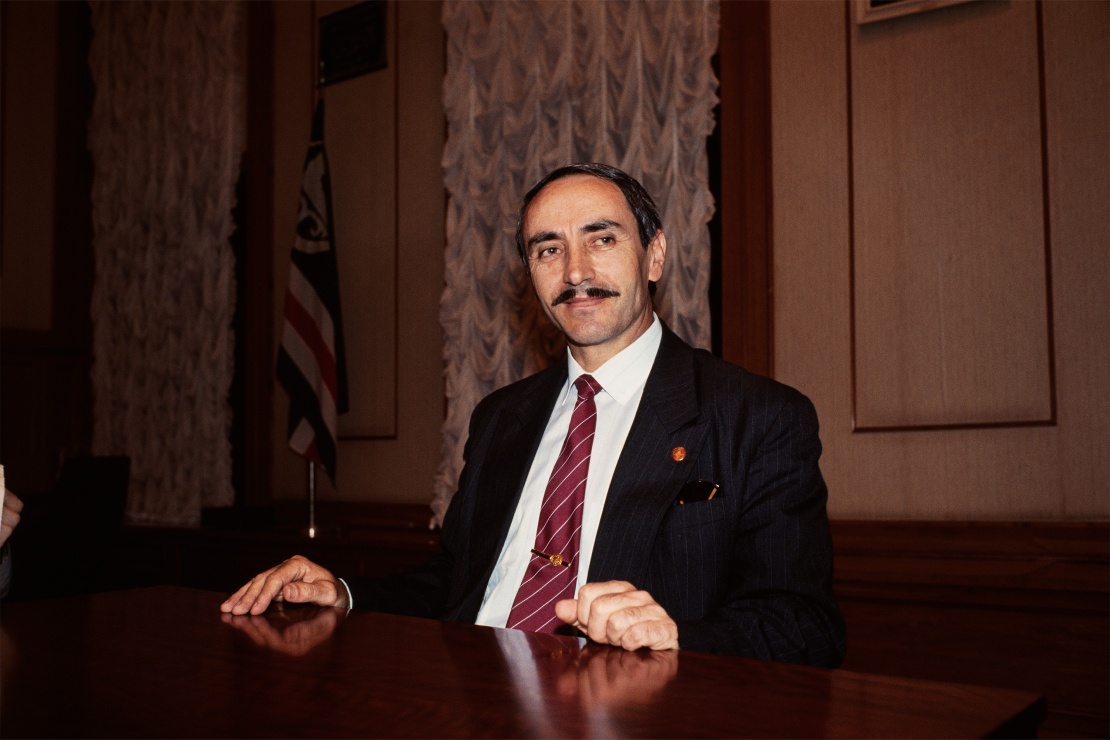

The first president of the independent Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, Dzhokhar Dudayev (killed in 1996), October 1992.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

However, the Kremlin did not legally recognize the independence of the Chechen Republic and tried to return it to the Russian Federation, first – by negotiations, then by a transport and economic blockade. When this did not help, in late 1994 Moscow launched a military invasion, which they called the "operation to restore the constitutional order". The tactics of the Russians were about the same as they are now in Ukraine – massive air bombardments, missile and artillery shelling of cities and villages, including with ammunition prohibited by the international conventions. As a result, thousands of civilians were killed. But in direct military clashes, the Russian troops suffered heavy losses. As a result, in August 1996, the Russian Federation and Chechnya signed a peace treaty. Russia began to withdraw its troops from the Republic, which retained its independence, and the Kremlin actually admitted defeat

Grozny, the capital of Chechnya, after shelling and bombing by Russian troops, January 25, 1995. A Chechen woman on the streets of Grozny after the fighting, January 5, 1995.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Russia launched the new invasion of Chechnia in August 1999. It was the "PR campaign" of the then-head of Federal Security Service (FSB) and the future actually permanent "president" Putin. This time the invasion was called the "counter-terrorist operation". By April 2000, the Russian troops had actually occupied the territory of Chechnya. The rebels switched to guerilla tactics, and some leaders took hostages similarly to how it was in Beslan or Moscow. The pro-Russian administration was appointed in Grozny. The head of that administration was Akhmad Kadyrov, the father of the current head of the Russian-controlled Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov.

A building destroyed by Russian shelling in Grozny, October 1999. Russian artillery shelling Grozny, December 1999.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

The "counter-terrorist operation" regime in Chechnya was canceled only in 2009. But almost the entire North Caucuses continues to fight against the federal government. In addition to Chechnya which was fighting for independence, there are movements for at least autonomy in Dagestan, Ingushetia, North Ossetia-Alania, Kabardino-Balkaria, and Karachay-Cherkessia.

A poster of Ramzan Kadyrov and Putin hangs on the wall of a war-torn building in Grozny, November 28, 2005.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Tatarstan

In 1990, the Tatar Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic adopted a declaration of state sovereignty and was going to participate in the reorganization of the Soviet Union. But after the August Coup of 1991, the Republic leadership headed for independence and in October of the same year adopted the Declaration of State Sovereignty of the Tatarstan Republic.

In March 1992, a referendum on the independence of Tatarstan was held. Despite the Kremlinʼs attempts to prevent it, 61.4% of the population voted to live in a sovereign state. And on November 30, 1992, the Constitution of the Republic of Tatarstan came into force, securing its state sovereignty.

Tatarstan, like Chechnya, refused to sign the Treaty of Federation. Though the Kremlin was not going to recognize the independence of Tatarstan, unlike in Chechnya, this time it decided to act by political methods and at the first offered serious concessions. After lengthy negotiations in 1994, Moscow and Kazan concluded a unique agreement, according to which Tatarstan became not a subject of the Russian Federation but a kind of sovereign "state within a state".

According to this agreement, Tatarstan could have its own Constitution and legislation, its own citizenship, tax system, could manage its own income, establish its own relations with other subjects of the Russian Federation and even with foreign states and independently trade with them. And all the natural resources on the republic territory were declared "the exclusive legacy and property of the people of Tatarstan".

When Putin came to power, the privileges of Tatarstan began to be gradually limited. In the early 2000s, changes were made to the Constitution of the Republic, now Tatarstan was named a subject of the Russian Federation, and internal citizenship was abolished. In 2007, Kazan and Moscow signed an agreement on the delimitation of powers for a period of ten years. It no longer included the former financial preferences for the region, including a reduced percentage of tax deductions to the center, and natural resources were no longer claimed to be the legacy and property of the people of Tatarstan. By 2017, the entire independence of the republic had become so symbolic that the new treaty was not even signed.

Russian President Boris Yeltsin (right) in Kazan during his election campaign for the second presidential term, June 11, 1996.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Tuva

In the early 1990s, in Tuva, there were calls for independence from Russia as in other post-Soviet republics. The peopleʼs front "Khostug Tuva" ("Free Tuva") became the speaker for these ideas. In December 1991, the republic introduced the post of president, who also functioned as the head of government. In 1993 Tuva adopted the Constitution.

Tuva eventually signed the Treaty of Federation with Moscow while arrogating some powers not been envisioned in the Treaty. For example, Tuva received the right to self-determination, as well as the right to resolve military-political issues and the issue of citizenship without discussion with the center, as well as to reorganize the judicial system.

Putin in front of the cameras “having lunch” with a resident of Kyzyl, the capital of Tuva, 2009. Today, the Republic of Tuva ranks last in terms of quality of life among the regions of the Russian Federation.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

In this case, the Kremlin also took the path of diplomatic bargaining and pressure. By the mid-1990s, the "Khostug Tuva" party had already ceased to exist. And by 2001, about 60 different changes were made to the new Constitution of Tuva, which limited its independence. The new amended Constitution no longer spoke of sovereignty, the article on local citizenship was abolished. The post of president was also liquidated; now, the head of the region was the chairman of the government, who is appointed in the Kremlin.

Ural Republic

In the aforementioned examples, the desire for independence was based, first of all, on a national basis. However, the story behind the Ural Republic was about an attempt by the regional political elite to gain more economic and legislative autonomy against the backdrop of the weakening of Moscowʼs control following the collapse of the USSR.

The Ural Republic emerged following the referendum held in the spring of 1993, which raised the question of creating an autonomous republic within the Russian Federation covering the Sverdlovsk Oblast with a center in Yekaterinburg. More than 60% of the regionʼs population took part in it, of which more than 83% supported the creation of the republic.

A protester with the flag of the Ural Republic in Yekaterinburg, May 2019.

Already on July 1, the Sverdlovsk Regional Council decided to proclaim the Ural Republic and start working on the republican Constitution. In September, after a seminar of the heads of the Sverdlovsk, Perm, Chelyabinsk, Orenburg, and Kurgan oblasts, a long-term project appeared — the Greater Ural Republic within the boundaries of these regions.

At the end of October, the Constitution of the Ural Republic was ready. On October 31, it entered into force after publication at the Regional Newspaper. The white-green-black flag of the republic was approved in the Constitution, and elections of the governor and the bicameral parliament of the republic were scheduled for December 12. By this time, they even developed the design of the local currency — the Ural franc.

Banknotes of "Ural francs" printed in 1992. Ural and Siberian celebrities were depicted on the front side, memorable places on the reverse side.

Wikimedia

At first, Kremlin did not see these regional liberties as a threat. Still, already in early November 1993, the then President of the Russian Federation, Boris Yeltsin, signed a decree dissolving the Sverdlovsk Regional Council. Even though he did not have such powers at that time, he effectively liquidated the Ural Republic. And in the new constitution of the Russian Federation, a provision appeared on the equality of the subjects of the federation and the impossibility of their withdrawal from the state body unilaterally. Considering the fact that during the proclamation of the Ural Republic, all the legislative requirements that existed during the transition period from the USSR to the Russian Federation were met, de jure it still exists.

Siberia, Far East, Yakutia, and others

Autonomist sentiments have existed in Siberia since the 19th century. In the early 1990s, ideas about creating the Siberian Republic were raised at a meeting of the Association of Siberian Cities. But then, this idea did not find large-scale support. At the same time, the major claims of Siberians still persist. After all, this is a region rich in minerals, and they deposit their main income to the federal center.

In 2014, against the background of the Kremlinʼs support for the "L/DPR" quasi-formations, it was planned to hold the so-called marches to federalize Siberia, the Urals, Kuban, and the Kaliningrad oblast, during which the slogan " Stop feeding Moscow” was announced. The Kremlin reacted quickly: they blocked the groups of organizers on social networks, and some activists were detained and fined. As a result, the march was never held in any of the regions.

A demonstration by mothers protesting against Moscowʼs failure to pay family allowances in Krasnoyarsk, one of the largest cities in Siberia, on October 2, 1998.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

In the early 1990s, the Far Eastern elites proposed creating the Far Eastern Republic. As a historical precedent, they recalled the independent state that had existed in this region in the early 1920s. In the late 2000s, during rallies that began for economic reasons, the region again voiced the ideas of the formation of the Far Eastern Republic and its possible secession from the Russian Federation.

And that is not all. There are similar trends in Yakutia, Buryatia, Bashkortostan, Kuban, and other regions. Ideas of unification with Finland are popular in Karelia. And Kaliningrad oblast, which does not even have a common border with the Russian Federation, has been repeatedly put forward from ideas of transformation into an autonomous republic to secession from Russia.

Translated from Ukrainian by Olya Panchenko .

"Babel" needs support from its readers now more than ever. If the work we do is important to you, please, send us a donation !

«Babel'»