1.

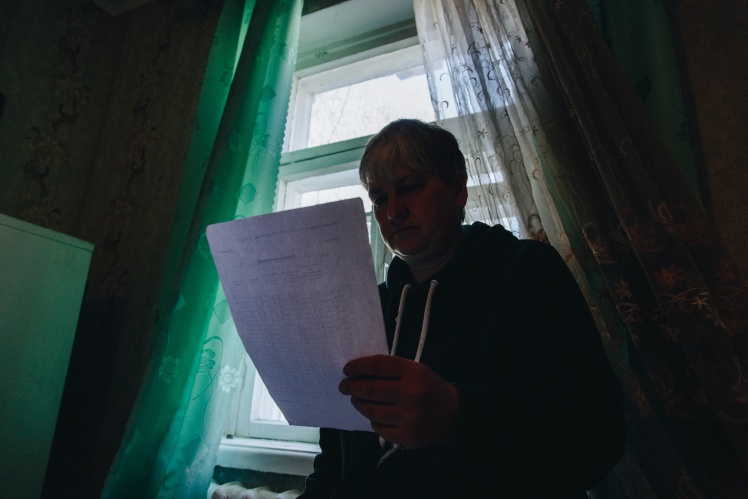

Vira Stadchenko is 49 years old. She enters the house and the first thing she puts on the table is a green folder with documents and a photo of her missing son Vadym. Apart from the table, there is almost no furniture in this room — Vira comes here only to take care of her mentally disabled sister. And she also takes care of her sonʼs house. The son disappeared in July 2022.

Vira is from Radomyshl, a small town in the Zhytomyr region, a 100 km to the west from Kyiv. Vadym is her eldest son, there is also 12-year-old Maksym and eight-year-old Denys. Vira gave birth to Denys after her one-month-old daughter died. Vadym took Maximʼs upbringing upon himself: Viraʼs first husband and the boysʼ father died, and she divorced the second one.

Vira Stadchenko. Vadymʼs younger brothers are Maksym (fair-haired) and Denys. Vira always has a folder with documents and a photo of Vadym with her.

Діма Вага / «Бабель»

In 2014, 18-year-old Vadym went to fight in the ATO and served there for three years. Then he returned to Radomyshl, provided Internet services in the city, went to the local Protestant church. He also took Maksym there. Vira had enough strength only for the younger Denys — after the death of her daughter, she was nervously exhausted, then she had to take care of her father after a stroke. Vadym officially became the breadwinner of the family. In the summer of 2021 he began to furnish his own house, but he saw his mother and brothers every day.

On the twenty-fourth of February, Vadym went to the 95th Brigade of the Ukrainian Armed Forces. In March, he defended the Kyiv region — along the road leading to Radomyshl. After several months of training, he was transferred to the 46th Brigade. At the beginning of July, Vadym came home for two days, and then in his car, together with other soldiers, went to the Kherson region.

"He called every day, or we called him," says Vira. “He always said: "Mom, everything is fine.”

They last spoke on July 25 at 12:50 p.m. The next day there was no contact with Vadym. On the twenty-seventh of July, Vira was at her parentsʼ home when a death notice was brought from the Military Commissariat.

“I thought I would lie down right there,” says Vira. “They said that three bodies would be brought the next day. We ordered a canteen, a loaf of bread, as expected, bought towels, and were going to dig a hole. People started [gathering] in the corridor. They brought two [bodies], but there was no Vadym.”

Vadymʼs fiancee, whom only the younger brother knew about, also arrived and waited with everyone for two weeks. They promised to bring the body several more times, but nothing happened. The plot for the grave was left to the Stadchenkos.

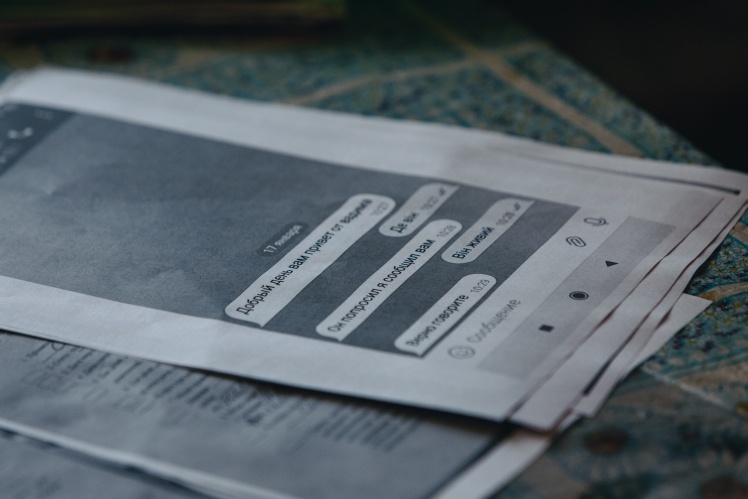

All August, Vira was waiting for the funeral. She called Vadymʼs military unit numerous times. At first she was told that Vadym had died, and after a few days — that he had deserted. Later — that Vadym is considered missing. Vira wrote several posts on Facebook that she was looking for her son, added his photo and her contacts. Almost immediately, an unknown person wrote to Vira in Telegram that Vadym was alive and in captivity. The message was deleted as soon as Vera read it, and a few weeks later, at the end of August, the Russian called.

Діма Вага / «Бабель»

Vira turns on this conversation — on the recording, she asks in Ukrainian to send a photo of her son. The Russian refuses. Vira asks to let Vadym say at least a word, so as not to go to the cemetery to cry. But the Russian says: "I will not do this. A million percent he is alive, so donʼt start." Vira is sure that they were not scammers: at first they asked for money for her sonʼs photo, but when she was ready to send it, they refused.

In the fall, a family from Ternopil contacted Vira. They buried the body of a man whom they had previously recognized as their son. But they saw in Viraʼs post a photo of Vadymʼs necklace, which he wore around his neck — they were allegedly given the same one with the deceasedʼs belongings. So they think they actually buried Vadym.

At first, the woman believed that her son was really buried in Ternopil. An investigator from Kryvyi Rih, who was handling the case of the Ternopil family, called her and asked her to take a DNA test. A month later, the investigator called again — there is no match in the test, but it must be retaken.

While Vira was waiting for the conclusion, she already doubted that her son was buried in Ternopil. In September, she and a group of relatives of other missing persons went to a meeting at the Coordination Center. A woman who allegedly buried her Vadym in Ternopil came there. She showed Vira a photo of the body — there was an imprint of a cross on the chest, and Vadym never wore a cross, because this was the rule of his Protestant church.

"I immediately accepted everything, I thought it was definitely my [son], but when I was shown this photo, itʼs different bodies," says Vira, searching her phone for a photo of the body that was sent to her for identification. “No eyebrows, no chin, just a round little face. And he had a long one. Well, look.”

The body in the photo is already bloated, but if you look closely, as Vira insists, you can see the differences in the shape of the chin and eyebrows. A photo of Vadym in uniform is lying on the table in a frame.

Vadym Stadchenko-Galyona. Medal for participation in the ATO and Vadymʼs diploma. Grandmother Liudmyla says that Vadym slept on this sofa in his childhood, when his mother worked and he stayed with his grandmother.

Діма Вага / «Бабель»

Since August, Vira has been trying to talk to her sonʼs colleagues. They say that the command has forbidden to disclose anything. Those who did give a shred of information said different things: he was either wounded in the back or torn apart by a shell. The military unit said that they believe Vadym is alive and assume that he is in a hospital in the occupied territory. The evacuation team, which worked in the places where he allegedly died, did not take his body out. Vira began looking for her son in the occupied territory through acquaintances. But they quickly refused to help because of threats from the occupiers.

In November, a woman wrote to Vira with a similar situation: a DNA test showed that her son had died, but she later found him in captivity. While watching numerous videos, the woman saw a man who looked like Vadym on one of them and wrote to Vira.

“Does he look similar?” Vira shows the screenshot. “Oh, he is thinner in captivity, but does he look like my child? Why did I riot?”

The man in the video really looks like Vadym in the photos from several years ago. Half of his face is hidden by a buff — Vira says that he often wore it and did not like to be photographed. When and where the Russians filmed this video is unknown.

The woman who sent the video to Vira advised her to contact the International Commission on Missing Persons, an international organization that searches for missing people due to war. In February, Vira went to them in Kyiv, took a DNA test for the third time, and handed over a printout of the previous DNA test to be decoded and told if the result was accurate.

The Stadchenko family in the yard of grandfather Yuriy and grandmother Lyudmila. Lyudmila says that her husband Yuriy, when he saw the screenshot from the capture, treated everyone at the market and is now waiting for his grandson.

Діма Вага / «Бабель»

Vira received the results of the DNA examination of the Ternopil family only in January. The test showed that itʼs 99.99% that Vadym was the buried one. But she doesnʼt believe it and shows a printout with numbers: she says that she and another mother from Ternopil have the same indicators, and it shouldnʼt be like that.

They stopped communicating with the Ternopil family: they demand that Vira admit that it was Vadym who was buried, and they continue the search for their son, but Vira does not agree to this. Now she is looking for a woman whom she saw on a video from captivity next to a man who looks like Vadym. She has allegedly already been returned to Ukraine.

“Iʼm looking for her to confirm. The video shows that it is my child,” says Vira. “If itʼs not, I would accept it and take [the Ternopil body] away. I agree with everything. Only [need to know] the truth.”

Vadymʼs mother shows the suit that her son bought for the wedding. Vadymʼs chevrons on tulle in his house. The youth church to which Vadym goes. People don't wear crosses there, also there are no icons.

Діма Вага / «Бабель»

2.

Oleksandr Grebenyuk has been in charge of the Rivne evacuation brigade for a year, which transports the bodies of fallen soldiers from morgues to the burial place in two cars. During this time, the team transported more than a thousand bodies from 15 morgues. Oleksandr listens to a short retelling of Viraʼs story and tells his own:

“My third cousin has been in captivity since March 2022. For three months we thought he was dead. And in December he was exchanged. Now heʼs in the army, again.”

It is in the morgues from which Oleksandrʼs group takes the bodies that they usually take a DNA sample of an unidentified person. Or in mobile laboratories that come to the place of exhumation of mass graves. Relatives write a missing person report to the police, investigators open criminal proceedings. The closest relative submits DNA, the sequence is deciphered and entered into the all-Ukrainian database. Coincidences are being analyzed in NDEKC, which is the only one entitled to such a study.

When there is a match in the samples of a living person and a dead person, they are assumed to be related. A letter about this is received by the morgue where the body is kept. There they already give the final conclusion. For a more accurate result, another relative may be asked to submit DNA to compare several samples and find the necessary matches.

Mass burials.

Oleksandr says that morgues tell him about frequent cases of errors in DNA tests. During a year of work, he outlined the main problems related to the identification of the dead. One of them is that people in units donʼt know each other well. Often the commanders themselves confuse who died. For example, the deceased had with him or picked up the things and documents of another soldier, who died earlier. Over the course of a year, Oleksandrʼs team encountered such a situation twice — bodies with other peopleʼs documents were mistakenly brought for burial. In such cases, the body is simply returned to the morgue from the funeral, and then relatives are searched for DNA.

"Another problem is that no one was ready for such a trouble, which is happening now,” says Oleksandr. “There are not enough machines [for DNA testing], and there are not enough people who know how to do it.”

But still the biggest problem is that relatives do not want to believe that their loved one really died.

“Sometimes they donʼt believe at all. To the point that in the middle of the night, the guys carrying the body stop and take pictures of the bodyʼs, Iʼm sorry, balls, because the woman said there must be a scar, and she needs to make sure. And even when that scar is there, they still say that itʼs not him — they only accept it when the body is brought with the personal belongings. Or the father "doesnʼt recognize" his son, because there is no face on the body, but all the tattoos on the body are his. That is, this lack of perception is the biggest problem.”

Natalka Bagriy from the Patronage Service "Azov" works specifically with relatives who are looking for bodies. For a year, the service has been accompanying the families of "Azov" fighters in the search for the missing, DNA identification, burial and return from captivity. In order to start the search, she advises relatives to write a statement immediately to the regional police department, so that they can already transfer it to the regional department. In small towns or villages, relatives may simply be refused.

Natalka says that the system is loaded, but itʼs coping. There are difficulties in extracting DNA from the body due to the deep stage of decomposition. Then they try to extract the DNA several times, and this is a long process. But the main problem is not related to the research itself — it is the investigators who do not enter the samples into the general database.

“If relatives gave their DNA, but the test is not in the database, then most often the investigators are to blame, not the NDEKC,” Natalka says. “It often happens that when transferring information about DNA between investigators of the region, district or different regions, it is simply lost. The investigator does not follow the progress of the case, and everything stops. Then the DNA must be transferred to relatives.”

Natalka says that the only way out for relatives is to control the actions of the investigator from the very beginning. Constantly calling, clarifying what has changed in the case, seeking to enter DNA into the database.

Exhumation of bodies in a mass grave.

“It happens that investigators send relatives for DNA testing and stop contacting them,” says Natalka. “Then you need to get them, call the hotline of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. There is no violation, but it is unethical. The human factor plays a role — after a year of working with it, they become as angry as dogs.”

The worst thing for relatives is to wait. Sometimes it lasts six months, or even longer.

“This is the most hellish thing,” Natalka says. “But I donʼt have any criticism regarding the work of NDEKC itself, itʼs just a long time.”

3.

DNA data of relatives who are looking for missing persons are collected in a single database included in the system of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine. But this database is universal — it stores data of those who are trying to establish paternity through the court. Therefore, the base is very extensive and not specialized.

When searching for missing persons, only one of the relatives gives DNA — father or mother. In fact, this is not enough for accurate results, the International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP) explains. It is because of this approach that situations like Viraʼs — with an uncertain DNA test result can arise.

ICMP was created in 1996 to search during the wars in the Balkans in the 90s, when tens of thousands of people disappeared. Most of them were killed and buried in mass graves. Some bodies were reburied several times, their remains remained in different graves. The usual DNA test, which assumes that this is the body of a specific person, did not work here. Then ICMP was the first to use a method where all the DNA profiles of relatives were compared with the DNA profiles of all recovered bodies: the search profiles included samples of several family members, data on the location of the burial, the results of identification of the bodies. There was a lot of data, so a new system was created for them. This was done in Bosnia and Herzegovina. This principle helped to identify about 24 thousand people from mass graves. For this, about 73 thousand DNA samples were collected.

Mobile laboratory for passing DNA tests. Such equipment is provided to Ukraine by international partners and ICMP is ready to hand it over.

“This is an unprecedented achievement, the worldʼs most successful search and identification process,” says Matthew Holliday, who leads the search program in the Balkans and now in Ukraine. “We offer the same to Ukraine. We do not promise to find everyone, it is impossible. But we can improve the search results.”

When full-scale war broke out, the Office of the Prosecutor General of Ukraine turned to ICMP for help. After several meetings with the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the organization and Ukraine exchanged diplomatic notes and began cooperation. ICMP should give its system to create a single base. The draft Agreement on full-fledged cooperation was agreed back in June, but it has not yet been signed. As long as the ICMR does not have legal status, it cannot hire enough staff, open bank accounts and provide equipment and reagents for tests. But the main thing is that the organization cannot work with a large amount of data and does not have the right to export samples for testing in the Hague, where a new laboratory is being created for Ukraine.

Without a Cooperation Agreement, ICMP does not collect samples from refugees whose relatives have disappeared. The team canʼt even publicly talk about themselves in Ukraine, the organization is found via “word of mouth” — thatʼs how Vira, Vadymʼs mother, found it. On behalf of relatives, ICMP is asking investigators for permission to take a DNA sample from a specific body or all unidentified bodies in the morgue. So far, ICMP works for free with such individual appeals and trains Ukrainian human rights defenders and forensic experts.

Ukraine and ICMP do not exchange data, because Ukraine has not approved the European GDPR personal data protection standard. So relatives who ask for help usually submit DNA again — Matthew Holliday worries that this process traumatizes them, and everything should be simplified as much as possible. This is impossible without the Agreement.

Matthew Holliday adds that the ICMP system is used in Iraq, Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. There was no data leak, which, according to the ICMP teamʼs assumption, the Ukrainian side is afraid of. So why the Agreement has not been signed yet is a mystery.

“Why there is no political will for this is a million-dollar question,” he says. “We were approached, asked to help, we drew up a draft, the case moved forward, but everything stopped. We are trying to figure out how to change that. It seems that the issue is in the cooperation of the Ministry of TOT and the Ministry of Internal Affairs. But we are not here to compete with the police — we offer a partnership, we will simply provide our programs, support, laboratory facilities in the Hague, which are being developed specifically for Ukraine.”

A doctor takes a sample of epithelial tissue from the cheek of a person who is looking for a missing relative.

One of the ICMP employees says off the record that it seems that the Ministry of TOT does not want to cooperate — because of competition.

Another ICMP employee explains that a separate DNA database of those who disappeared precisely because of the war has not yet been created. Data on the missing can be held by various departments — the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Health. Volunteers and non-governmental organizations are also working to find the missing and have their own data. ICMP has already processed about a thousand appeals — it is possible to work with individual cases even without an Agreement. DNA samples were analyzed in The Hague. But the already long process is slowed down by numerous permits from the police, without which the organization cannot take DNA from bodies in morgues.

“A thousand is nothing on the scale of the country. But considering that we do not advertise our presence in Ukraine, it can be concluded that people are desperate and looking for any way. Some refugees even came to our office in the Hague. Thatʼs how people want to find it!” says the ICMP employee.

Vira Stadchenko holds on for the sake of her younger sons. She mistakingly calls them "Vadym" from time to time. Vadymʼs uniform and washed belongings and his trunk, which were given by other soldiers, are kept by Viraʼs parents. Sometimes he has the strength to come to his sonʼs home, which he has just begun to furnish. This is her old ancestral house. Despite the fact that there is nothing to steal there, robbers have already broken into the rooms several times. It is difficult for Vira to get there. She says that the storks built a nest nearby and that should be a sign of good luck. About the place where the house stands, she adds:

“If, God forbid, [Vadym is really dead], it will be Galyona Street. Here [in Radomyshl] we call it that — after the dead [military men]. There are already two such streets in Radomyshl.”

Vira hopes that there will be no third one.

Grandmother Liudmyla shows the washed uniform of grandson Vadym. Vadymʼs house, next to which the storks made a nest.

Діма Вага / «Бабель»

Translated from Ukrainian by Anton Semyzhenko.

Support Babel: 🔸 in hryvnia 🔸 in cryptocurrency 🔸 via Patreon 🔸 or PayPal: [email protected].