Museums

When Oksana Semenik was four years old, in the summer she and her mother went to Feodosia town in Crimea. There, she was struck by two things — the sea and the Aivazovsky Gallery. The gallery was small, so the canvases were hung on the walls in several rows. Oksanaʼs first childhood memories are connected with this: she, a little girl, stands in this small gallery, and above her is a vault with paintings, and this does not disturb, but on the contrary, it calms. Then Oksana went to an art school, where she always drew the sea. Her mother raised two children on her own, so they rarely traveled. But entrance to Kyiv museums for children was free. This is how Oksana began to learn about the world of art.

"As a child, I wanted to know the story behind each painting," she says.

As an adult, Oksana came to the same Kyiv museums and noticed that she reacted differently to what she saw. Museums taught her to ask herself new questions and hear new answers, showed the experience of distant and unknown people and countries. Arriving in a new city or country, Oksana made it a habit to go to local museums — thatʼs how she learned about the context, culture, and history. She liked to walk, for example, through a gallery in Krakow and with the paintings to study how Poland was changing.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

In 2017, Oksana toured the Donetsk and Luhansk regions with the "Museum is open for renovation" project. Then she realized that museums in small front-line towns can also be important and help to work with what was experienced during the war. At the end of 2021, Oksana began writing a thesis on post-Chornobyl paintings and moved to Bucha.

Bucha

In Bucha, Oksana lived at the "Sklozavod" — thatʼs what the locals call the residential area near the Bucha glass factory. In November 2021, her boyfriend, Kyiv videographer and photographer Sasha Popenko, moved in with Oksana. Oksana recalls that she really liked Bucha. The apartment was spacious and cozy, near the forest and the lake. Life seemed quiet and safe, so when news broke in November 2021 that the Russians were planning to attack Kyiv, Oksana wasnʼt worried.

"We imagined that bombs would fall on Kyiv, and the Russians would attack from Donbas," she recalls. “Sasha and I were joking: who would go through the Chornobyl zone anyway?”

On February 25, 2022, Oksanaʼs father was supposed to take them to the village to Oksanaʼs grandmother. But he couldnʼt leave Kyiv because of roadblocks. Oksana, Sasha, and their cat Vatrushka first went down to the basement of their five-story building, and then “moved” to the better equipped basement of the neighboring kindergarten. They spent two weeks there with other locals. Sasha sometimes went out to photograph the district, Oksana read "Toreadors from Vasyukivka", took care of the cat, played with the children, thought about what books and articles to write, dreamed of getting to the Hermitage to return the looted by the Russians.

On the third day in the basement, after she and Sasha did not dare to evacuate, Oksana fearfully asked what was next. He answered:

“Well, letʼs start a family.”

“Maybe then you will say it normally?” she specified.

“Will you marry me?” Sasha asked.

Oksana recalls that she joked that she would die engaged, but she always said that they would get out. The wedding was planned for Independence Day, August 24. In the basement, they discussed where to celebrate, what the dress would be, who to invite as a photographer, and who would be on the guest list. In the meantime, real life became more and more unbearable: they saved on food and water, didnʼt wash, used a bucket for a toilet, slept with their clothes and shoes on.

Олександр Попенко / «Бабель»

On March 10, the head of the Kyiv Military Administration, Oleksiy Kuleba, announced that a humanitarian corridor for evacuation would be opened from Bucha. Oksana and Sasha dared to go out. They walked in a large column, they did not know if it was safe and where the Zhytomyr highway would lead. Surprised Russians let the column pass through the checkpoints. In total, Oksana and Sasha walked about 20 kilometers.

“I shed a tear when I saw the Ukrainian military at the checkpoint,” Oksana recalls, and even now she is glowing at this moment. “I canʼt even describe this happiness. I showed my passport, passed behind the backs of the Ukrainian Armed Forces — and you immediately feel safe, because no one will kill you simply because you exist. I just couldnʼt believe it.”

After leaving Bucha, Oksana heard the roar of tanks, dreamed of the occupation, she was afraid to wake up in the basement. She still tries not to think too deeply about what she experienced in order to hold on. She says that her experience of occupation is not so terrible compared to that of Kherson. She says that she would rather never mention it — and at the same time she is terribly afraid of forgetting.

“God forbid that children and grandchildren are taught incorrectly,” says Oksana. “They should know all this. That a Muscovite is an enemy. The one that will attack, steal, kill, even if a person seems normal. The next generation should not forget, as we did not forget the Holodomor.”

Oksana and Sasha got married in August in Kyiv, where they now live. Everything was pretty much as they had planned in the basement, except for the date. The wedding was moved to the beginning of the month, because on August 24, Oksana boarded a train to Poland, from where she flew to the United States.

USA

In April, a former colleague, Daria Badior, wrote to Oksana and asked if she would like to go to the USA for a few months to intern at Zimmerli, where curator Olena Martyniuk is looking for Ukrainian researchers. This museum has the largest collection of art in the West from countries that were once under Soviet occupation. Of course, Oksana would like to go there.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

But she hesitated. At first they offered to come for three months. Then they were not sure whether they would have funding. Even later — for Oksana to come for a year. After reading the last letter, she cried. She looked at the map — it was only an hour and a half drive from the museum where she was invited to her childhood dream, MoMA. Earlier, Oksana would not have even hesitated, but now she did not want to be away from her country and her fiancé for so long. In the end, they agreed that Oksana would come for the fall semester, and then decide whether she would stay.

At the end of August, Oksana arrived to Highland Park, New Jersey. The small university town was inhabited by Jews, Latin Americans, African Americans, and descendants of Ukrainian emigrants.

“I planned to study post-Chornobyl art,” says Oksana. “I knew about the need for decolonization, but I did not plan to do it.”

At the university, she was given access to TMS, the museumʼs digital database. To select works for research, Oksana set the time frame and filter “Ukrainian” in the search engine. The pictures were scarce. Then she became interested in what was painted about the Chornobyl disaster in Russia. In 1986, she came across the work of a "Russian" unknown to her, Yury Semash: an icon of George the Victorious, a paska, a didukh, and a candle. "The Russians have didukh?" Oksana was surprised. She googled: Semash was born and lived in Zaporizhzhia, and worked in Moscow for only a few years. Everything coincided: the work, dated May 4, a week after the explosion at the Chornobyl NPP, was one of the first to make sense of the catastrophe — because during the apocalypse, people are looking for God, even in spite of Soviet anti-religious censorship.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

Whose names did Russia try to appropriate?

Kazimir Malevich. Ukrainian avant-garde artist. Born in Kyiv in 1879, died in St. Petersburg in 1935. He taught at the Kyiv Art Institute, wrote in his autobiography that he was influenced by folk art. He showed the most famous Suprematist painting "Black Square" at an exhibition in St. Petersburg in 1915. Also, he created sketches for embroiderers in the Cherkasy region. In the 1920s, the Soviet authorities began to persecute the avant-garde. Malevich is forbidden to travel abroad, he starts working in Kyiv. Despite the censorship, he painted about the Holodomor. In 1930, he was arrested in St. Petersburg. He died of cancer five years later.

Ilya Repin. Or Ripin. He was born in 1844 in Chuhuyiv, Kharkiv region. Comes from a Cossack family. He painted pictures in the style of realism. He studied at a local topographical school, an icon painting workshop, at the age of 19 he went to study at the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts. From 1873 to 1876 he worked in France. After returning to the Russian Empire, he worked in Russia and Ukraine. Fleeing from the Bolsheviks, he moved to Finland, because he could not live in Ukraine. He died in 1930 in the village of Kuokkala, which was later occupied by Russia after the war with Finland in 1940.

Oleksandra Exter. One of the first artists who worked with the avant-garde. She was born in 1882 in the Polish city of Bialystok, but moved to Kyiv in her early childhood. There she studied at the Kyiv Art School. In 1907, he went to Paris, where he became interested in a new direction — cubism. A year later, she became a co-organizer of the first Ukrainian exhibition of modern art "Lanka", began to cooperate with embroiderers. After 10 years, she opened her own art school. In 1918, fleeing from the Bolsheviks, she left for Odesa, and six years later she emigrated to Paris. Exter spent only three years in Russia during her entire life, and thirty years in Kyiv. She died in 1949 in France.

Arkhip Kuindzhi. Landscape artist. He was born in 1841 in a Greek family in Mariupol. As a teenager, he went to Feodosia to study with Aivazovsky. Two years later he returned to Mariupol, later moved to Odesa. At the age of 27, he became a free student at the Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg. In the end, he returned to live in Mariupol, but went to exhibitions in Russia and Europe. In 1886 he moved to the Crimea. In 1910, he fell ill with pneumonia, on the advice of doctors he went to St. Petersburg, where he died. He painted Ukrainian landscapes, peasant life. His museum in Mariupol was destroyed by the Russians in March 2022.

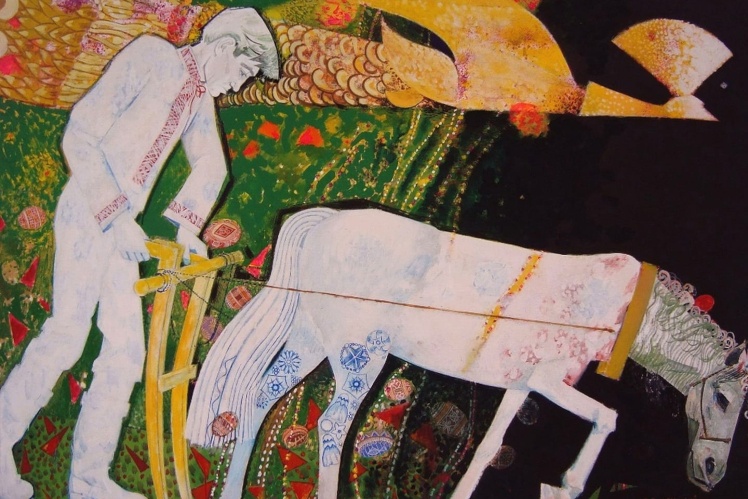

Fedir Krychevskyi. He was born in 1879 in the Kharkiv region. He studied at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, then at the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts. He studied for a year in Vienna with the artist Gustav Klimt. Due to the fact that he painted Ukrainian traditions, he was deprived of an artistʼs pension. From 1913 he worked in Kyiv. In 1917, he became the first rector of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts, which was closed by the Bolsheviks a year later. He taught in Kyiv, Kharkiv, his works were exhibited in Europe and the USA. After World War II, the NKVD arrested Krychevskyi. He was exiled to Irpin, Kyiv region, where he died of starvation in 1947.

Oksana wondered how many more Ukrainian names there are in the Russian section. She checked all 900 people, 70 of them were Ukrainians, another 80 were from other countries occupied by Russia.

“I did it quietly,” says Oksana, “and didnʼt talk about it until I processed 40% of the Russian database.”

Oksana made a presentation for two curators of the Russian Art & Soviet Nonconformist Art department — American Jane Sharp and Russian. Jane immediately took Oksanaʼs side: she used to research Russian art, but stopped after the full-scale invasion. The Russian woman argued. She called it “our, Soviet”, said that nationality is no longer relevant, and itʼs difficult to define it. Oksana disagreed: for several years in Moscow, a Ukrainian artist has not been transformed into a Russian one. She said that they donʼt write about Indian artists “from the British Empire”, just as they donʼt mention only the Third Reich when they talk about Germans. She explained that according to the principle of contemporary borders, one should write about UNR, but they do not do this. She reminded that it is wrong and indelicate to call Ukrainian cities Russian when Russian bombs fall on them. It was slow, but the arguments worked.

In the end, after arguments and with the support of Jane, they reached a compromise: the column "nationality" will be removed, instead, the place of birth, work and death will be written. However, it takes a long time — you have to change all the signatures in the systems. So the process is now ongoing.

On free Fridays, Oksana went to New York. She went to MoMA, which she had only dreamed about before. In addition to delight, she felt disappointment: Ukrainian Malevich and Ekster were signed as Russian. In the room with Picasso, Gauguin and Matisse, not a word about African art, which they were inspired by and called primitive at the same time. In the hall about America in the 1960s, they did not write about Vietnam. At the exhibition about Ukraine, “In Solidarity”, there is not a single word about Russia waging war against Ukraine. It was even more surprising that the same Malevich and Ekster in this exposition were Ukrainians after all. Oksana did not see the expected context, discussion, statements, work on important topics.

MoMa museum.

www.moma.org / «Бабель»

From the USA, she continued to make projects in Ukraine. She was often tired. She was seriously ill twice, her hair began to fall out. The house where Oksana lived was not far from the airport — she woke up to the sound of airplanes and was afraid that the war had started. In recent weeks, she couldnʼt wait for the plane to Europe.

“When I said at the museum that I was taking the tickets home, they didnʼt believe me,” says Oksana. “Then there were massive rocket attacks, blackouts, so no one understood me. They thought that I was just an emotional Ukrainian who did not know what she wanted — and this is also a colonial way of thinking about others.”

Oksana returned to Ukraine happy. At home, she immediately felt better. She planned to rest, but continued to work with Ukrainian media and write to foreign museums about decolonization — both through personal communication in letters and through public questions on Twitter.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

Art and Twitter

Back in June, while preparing for a trip to the USA, Oksana started an English-language Twitter account — Ukrainian art history. First, she wanted such a channel to exist, and secondly, she needed to practice speaking about Ukrainian art to a foreign audience. It started with threads about Arkhip Kuindzhi, Fedir Krychevsky and Kateryna Bilokur. Twitter rapidly gained 1,000 followers. Now Oksana is read by more than 17 thousand people, and the account has turned into a full-fledged job for finding stories and works. Foreign media often ask her to comment on Ukrainian art, diaspora people upload photos of paintings from Ukraine and ask to identify who painted them, or share finds in American archives.

After researching in the US, Oksana began tagging specific museums to change the captions. Some responded to her personally: for example, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, after correspondence with Oksana, added the caption “now Dnipro, Ukraine” to “Ekaterinoslav, Russia” in the story about Helena Gerardia. In total, Oksana found another 40 Ukrainian artists in their database, who are registered as Russians — now she continues negotiations about renaming. She breaks the rules of the academic world and points out the mistakes of the MoMA, the Met, the Philadelphia Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Jewish Museum. Someone listen to her: the Met renamed Degasʼ “Russian Dancers” to “Dancers in Ukrainian Dress”, and wrote that Repin is Ukrainian.

"Enslaved Ukraine", Kazimir Malevich, 1930s.

WikiArt / «Бабель»

“But with someone itʼs more difficult. The Brooklyn Museum replied that it would take them years to conduct their own research on this topic,” says Oksana. “On some works it is written that they relate to Ukraine ― for example, Repinʼs “Russian Winter Landscape” has the authorʼs signature “Chuguyiv”, and this is the Kharkiv region. That is, the landscape isnʼt Russian. And Repin himself called Ukraine his homeland. To which the museum replied that he died in Russia, although in fact it is the occupied Finnish village of Kuokkala, where he deliberately moved away from Russia.

Such explanations take a lot of time and effort. Oksana has to argue with people who should have a subtle understanding of contexts, but succumbed to Russian propaganda. She says that for years, Russia turned the Ukrainian avant-garde — Malevich, Exter, Burlyuk — into one of the pillars of its own propaganda. The Bolsheviks claimed that it was their revolution that gave rise to the avant-garde, which speaks of freedom, individuality, and a new order. In fact, the direction was formed even before them. And the Soviet authorities then censored it, throwing out their opponents from galleries and books. At the same time, avant-garde artists had connections with Ukrainian traditional art, and communicated with embroiderers.

Oksana suspects that the issue is not only in the power of propaganda, but also in money — for example, many paintings by Ekster were given to the MoMA and Met museums by a Russian collector. Still, she hopes that public campaigns will work. Just as it happened with Arkhip Kuindzhi — Oleksandra Kovalchuk from the Odesa Art Museum got the Met to write about him not as a Russian, but as an Armenian born in Ukraine, and to note that his museum in Mariupol was destroyed by the Russians.

In order to do this more effectively, Oksana will start working in a large Ukrainian museum from March. Then she will be able to speak not just as an activist, but as a representative of the institution — in the academic world this is important.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

“Iʼm doing this because I am personally angry that our artists are undervalued, that Russia kidnaps them and presents them as their own. And then people think that Russians are cool,” says Oksana. “This affects the fact that in the West they do not believe that people with such a culture can commit such terrible crimes. But Russian culture is a myth. The real one doesnʼt work. Otherwise, there would be no crimes by Russians in Ukraine, Chechnya, Georgia, Syria. Because culture is not only “high art”, it is also a worldview.”

And for Oksana, it is important that people learn about Ukraine abroad — the signature under Malevich can be an impetus for this.

“We still have a Soviet perception, but museums are powerful institutions that conduct research, make statements, reflect, popularize art, and create public space,” explains Oksana. “I think that in Ukraine, museums can study, for example, the topic of war trauma, and this will unite people.”

She still tries not to comprehend what she experienced in Bucha because of pain and fear. She continues to work with a psychotherapist. She admits that she does not believe that all this — the occupation, the US, and decolonization — is really happening to her. But every day Oksana applies make-up — and necessarily glitter! The same ones she took to the basement in Bucha and imagined that she would apply them to herself and others to celebrate the day of de-occupation. Now she says:

“Well, why not shine if we are alive?”

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

Translated from Ukrainian by Anton Semyzhenko.

Together with Oksana, we want to talk about returning Ukraine its art. Support Babel so that we evidence these news together: 🔸 in hryvnia 🔸 in cryptocurrency 🔸 via Patreon 🔸 or PayPal: [email protected].