Crime scene

A ten-minute drive from the Lisova metro station, there is a monument among the pines — a bent man with a bundle. The man is surrounded by crosses that look like cranes — according to Ukrainian legends, the souls of the dead are returned to the grave by birds. The man has a high forehead and an intelligent, humble face that would suit glasses. Actually, they were there until the end of the 90s, but they were often damaged as they were made from non-ferrous metal, so the city authorities decided to drop the idea of restoration.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

“This is what those who went into exile really looked like, this is the image of a repressed intellectual. But our people looked different”, says Tetyana Sheptytska. She takes us to the place where the Soviet Union tried to hide one of its bloodiest crimes — executions during the Great Terror.

The path from the highway between the pines is called the Road of Death. There is a lake, in which a truck used to wash off the blood in the 1930s, but now it is used by relatives of the murdered, tourists, and mushroom pickers. The bodies of the repressed were taken along another road, which was to the right, but in the 1960s and 1970s, the crime scene was planted with pine trees, and the road became overgrown.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

Tetyana has been working here for seven years, and her skin doesnʼt get goosebumps from being here:

“I feel a light sadness,” says the woman. She got to the burial in the forest for the first time, already working in the reserve. “Itʼs like visiting a cemetery with your relatives — itʼs sad, not creepy. Itʼs creepy to me at Lypska Street, 16: our office is directly above the shooting cellars.

In the early Soviet period, Lypska was called “the longest street in the world” — you could come there and never return. It was convenient to take the bodies of those to whom this happened from Lypska, Zhovtnevy Palace and other central execution grounds in Kyiv to the special area of the Bykivnya forest.

Why this particular place was chosen isnʼt known for sure, but there are two possible reasons. First, at that time it was far beyond Kyiv. Secondly, at the beginning of the 20th century, there was a training ground of the Arsenal plant here, so the locals were used to not visiting the site.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

This land was allocated for the “special needs” of the NKVD on March 20, 1937 — the Kyiv City Council voted for this at a secret night meeting and also adopted a secret additional instruction. Historians still canʼt find it and learn its content.

All this was done in compliance with the operational order of the NKVD No. 00447 on the repression of “former kulaks, criminals and anti-Soviet elements." The order was signed on July 30, 1937. The mass executions were supposed to begin on August 5, but there was a false start in Kyiv — killings started two days earlier.

“This operation wasnʼt spontaneous,” says Tetyana. “It was secret, but it was prepared in advance: the officials instructed how to treat the arrested, where to keep them, what to do with the bodies. Large amounts of money were allocated for this — for the maintenance of people, gasoline, weapons, and rewards for NKVD employees. I know about 75 million rubles, it was crazy money.”

In the order, people were divided into categories with "limits". The "limit of the first category" — that is, those who must be shot — should be eight thousand people. It was planned to do it in four months. After all, the executions lasted for four years, and during this time, at least 100,000 people were killed in Ukraine alone. How many hundreds of thousands were sent to camps is unknown. The number is constantly growing.

"Similarly, no one knows exactly how many people are buried here," says Tetyana. “Historians say that from 20 to 100 thousand.”

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

Burials in the Bykivnya forest are the largest in Ukraine. During the period of the Great Terror, they were shot in every regional and district center, in the villages. Not all burials were formalized — in some places, bodies were simply thrown into a pit, buried in forest parks, in a cemetery, or on the territory of a prison. The murdered were buried in the Bykivnya forest from 1937 to 1941 — the NKVD shot people even when the German troops were on the approaches to Kyiv.

The Germans were the first to discover the mass burial — they conducted excavations, and in September 1941, the German Birzhova Gazeta in Berlin published an article about the mass shootings.

“This publication had a propaganda character to show that the German authorities have arrived and are liberating from the criminal regime,” says Tetyana. “But it was published right before the Babyn Yar massacre. So the Nazis no longer had the opportunity to pedal the topic of the crimes of the NKVD, because in fact their regime and the communist regime were equal in crimes. Twin brothers.”

In 1944, a Soviet resolution was issued on the crimes of the fascist-German troops, which generally referred to "burials in the Darnytsia Forestry." This was convenient, because the Nazi Darnytskyi concentration camp existed near Bykivnya. In the 1950s, Bykivnya was mentioned twice. Leontiy Forostivskyi, mayor of Kyiv during the Nazi occupation, published the book Kyiv between two occupations in Argentina. But it wasnʼt popular. Another passing mention is in the Canadian monthly Novi dni, where the shootings in Bykivnya and Vinnytsia were compared.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

Almost twenty years later, interested to Bykivnya arose again. In his memoirs, Les Taniuk described how a memorable evening of Les Kurbas was held in the club of creative youth Suchasnyk. After finishing, Taniuk was approached by a stranger and scolded that Kyiv has its own Solovky, which we need to talk about, ― Bykivnya.

"Then, on the waves of the Khrushchevʼs thaw, the first rehabilitations began, people dared to wonder where their relatives had disappeared to," says Tetyana. “But the sixties at that time had no idea what Bykivnya was and what the scale of the tragedy was. In the end, Les Taniuk, Alla Gorska and Vasyl Symonenko came here, and for a bottle of vodka, a local resident showed them the burial place. They saw scattered bones and children playing football with a skull.

Taniuk and his like-minded people could not reach the authorities. In 1961, a letter to influential members of the Communist Party in Ukraine demanding to explain what kind of burial it was and to honor the victims was ignored. Tetyana says that this story probably became one of the reasons for the repression against the 1960s: Vasyl Symonenko was beaten to death, and Alla Gorska was killed with an axe. Les Tanyuk was hiding in Moscow, and ten years later he wrote another letter to the authorities about Bykivnya. The government commission, which was convened in the same year, was a response partly to this appeal, partly to a report by the Ministry of Internal Affairs about looting at the burial site.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

The government commission worked under the strict control of the KGB and determined that fascist victims were buried in Bykivnya. Despite the meaningless conclusion, the commission also left behind something valuable — photos of excavated graves and officials directly involved in the lie.

“But here is the paradox,” Tetyana adds, “the Soviet authorities had already begun to [implement] the "cult of Victory [in the Second World War]," but nobody mentioned Bykivnya, where the victims of the fascists allegedly lie, at the official level. There were no commemorative signs, tributes, laying of flowers by pioneers.

For the first time, the truth about Bykivnya was told in 1989. Now another commission claimed that the victims of both the fascists and the NKVD were buried here. At the meetings, the testimonies of local residents were heard for the first time, but they were convinced that everything "just seemed to them". However, the prosecutorʼs office opened criminal proceedings and interrogated KGB pensioners who were transporting the bodies of the shot dead.

The case was closed as early as 2001 — then it was officially confirmed for the first time that the victims of Stalinʼs repressions, shot in Kyiv NKVD prisons from 1937 to 1941, rest in Bykivnya.

A place of memory

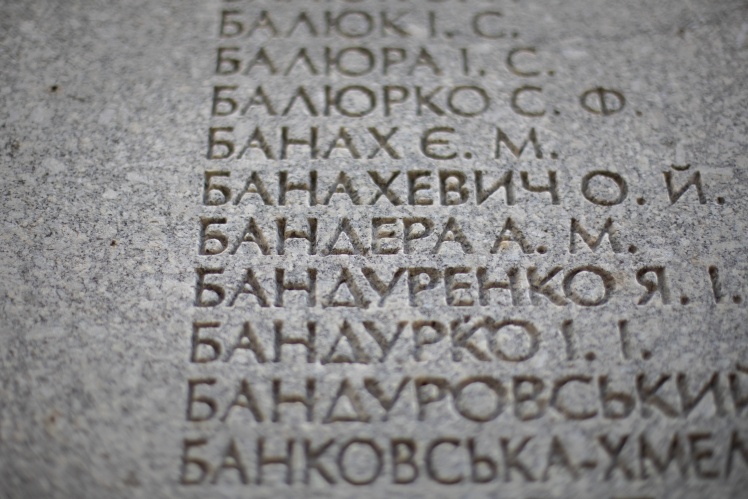

"These are all names, these are all, these are all names..." Tatyana repeats as we walk along the walls of the memorial.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

The walls are densely engraved with names. More than 18,000 people, including poet Mykhailo Semenko, father of Stepan Bandera, priest Andriy Bandera, writer Mike Johansen, artist Mykhailo Boichuk — and tens of thousands of well-known or completely unknown scientists, teachers, peasants, priests, unemployed, factory workers. About four thousand more names have already been uncovered, but there was no time to add them to the wall. Tetyana believes that there are at least twice as many people killed and buried in Bykivnya, i.e. more than 40,000. But she immediately emphasizes that the number, in principle, does not matter — a tragedy remains a tragedy.

Only a third of the entire territory was excavated, and most of the area was due to the construction of the memorial. People were buried at night in mass graves — pre-dug pits were filled with lime and soil. NKVD workers appropriated personal belongings and property even during arrests, later giving it to financial warehouses or selling in a shop on Prorizna Street. They also took the belongings of family members, although they had no right to do so even according to the laws of the USSR. During excavations in the 2000s, shoes, combs, glasses, and toothbrushes continued to be found here, sometimes with the name of the owner written on them.

Passing by the wall with names, Tetyana adds:

“This is a unique place. The destinies of people who otherwise would not have crossed paths met here. They were different in terms of social status and nationality, although the backbone was Ukrainians, and in terms of political beliefs — not all of those killed were opponents of the Soviet government, and not all were involved in cultural and intellectual processes. The Chekists, who committed terror in the 1920s, and then were themselves caught up in the "purges", are also buried here. But their names are not mentioned on the walls of memory. Executioners and victims cannot be together.

Along with Ukrainians, Poles, Greeks, Germans, Belarusians, Bulgarians, Macedonians, victims of the Harbin operation are buried here. Among all, memory of the Poles is the most visible: they built a separate memorial, and on trees, along with embroidered towels and blue-yellow ribbons, white and red ones are tied.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

Other parts of the memorial should tell more about the rest of the operations, but they, like, for example, the interfaith chapel and the exhibition center, were never built: there were only enough funds for the first stage of construction. It was completed in 2012.

"The second phase was planned to be completed in 2020, but there were no funds, there are none and, accordingly, there wonʼt be any soon," says Tetyana. “Maybe, in ten years in the best case. Although some things are really necessary — logistics, inclusion in tourist routes, transport. This is especially important for elderly people who visit relatives who have been shot.”

Only relatives of the victims come here — Tetyana has not met the children or grandchildren of the KGB workers buried here. Although the names of the executioners are in the documents. She says that she isnʼt sure that their relatives know about their familyʼs past at all, and society is hardly ready to talk about Soviet collaborators and to recognize this period as an occupation.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

But relatives of the victims, who had no relation to the repressive system, often turn to the reserve. Someone learns from the archives and comes to Bykivnya, joins all the activities, someone only guesses and writes requests. In such a case, the employees of the reserve look for a case on a specific person in the archives to report the details of who he or she was and under what circumstances he or she was detained. Sometimes it isnʼt possible to find a case — there is only an act of execution.

When the SSU archives were opened in 2016, work became easier. However, even by that time, the reserve had established the names of about 18,000 people buried in Bykivnya. At the time of the opening of the memorial, only surnames with the letters "B", "V" and "G" were engraved on the walls, so when Tetyana took office in 2015, relatives were still waiting.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

“For them, it was a constant question, why it happened like this, and pain,” says Tetyana. “So the reserve received an order from the Deputy Prime Minister for Humanitarian Affairs to complete the work on the walls and the list. Another 30,000 surnames were planned to be engraved after this, but we started checking them and saw problems. The list included repressed people not connected to Bykivnya — for example, Liudmyla Starytska-Chernyakhivska, Yuriy Gorlis-Gorskyi.

The first lists of those buried in Bykivnya began to be formed in the 90s — activists Mykola Lysenko, Leonid Avramenko, Mykola Rozhenko had access to the archives and transcribed the surnames they found. However, those who were shot in Sandarmokh, for example, or in the regional centers of Ukraine were mistakenly included in the lists. But Tetyana says that their work still was important — this is how the commemoration of the victims began. State institutions got involved much later, during the presidency of Viktor Yushchenko, who turned Bykivnya into an international place of memory.

In 2006, a Polish-Ukrainian archaeological expedition worked at the burial site and found the remains of bodies, personal belongings and a guard house from the 1930s. No remnants of the fence remained — after 1945, the Kyivites dismantled it for construction materials. DNA expertises werenʼt conducted. Scientific work on searching the archives began only in 2013: the reserve was created earlier, but there was no adequate funding.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

In 2009, the SSU published the first official lists of the buried on its website, but they were removed from the internet during the presidency of Yanukovych. It was these lists that the reserve requested in 2015 and started creating its own list based on them. They reread the acts and protocols of the executions, compared the data, checked the spelling of surnames, looked for errors in Russian spelling, namesakes and repetitions in the lists. There was no time to work with the archival and criminal cases themselves, which can contain hundreds of pages. And still thereʼs not enough time for this: just seven people work in the only scientific department.

"According to the charter, the reserve has the right to investigate all the repressions of the Soviet period, up to 1991, but physically we will not be able to do it," says Tetyana, as we walk to the two-story guard house. “We have several general directions, the rest are at the level of specific projects. In fact, every operation, every professional or social category, every period should be investigated separately by someone. As well as repressed NKVD workers, too.

It is in the guard house that the banners that the reserve uses for exhibitions are now kept. One of them shows photos from the excavations in 2011: found bones, combs, cigarette cases, buttons, toothbrushes, glasses, mugs. Last year, thanks to such a comb with the surname "Noga" scrawled on it, the archival file of the murdered woman was found in the Vinnytsia archive of the SSU. On several banners there are stories of the victims, and on another one — of the killers. And even in 2016, some visitors to the exhibition still asked whether the reserve was not afraid to talk about the KGB officers. Currently, a new exhibition is being prepared, but it is unknown whether it will take place.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

“This is still not a modern format of museum practices,” Tetyana admits, “but while itʼs the only one available to us, this is how we can show people not only the memorial complex itself, but also the documents.”

History in a circle

When the full-scale invasion began, some of the team of the reserve left Kyiv, some stayed, but in general the work continued — there are plenty of scanned documents. There was nowhere to take the artifacts, so they were simply packed and hidden.

“Of course, they have a human and historical value,” says Tetyana, “but not a financial one, so it wasnʼt us who was evacuated in the first place. There are no modern fund repositories in Ukraine, and the existing ones are not properly prepared. Therefore, the museum staff found themselves in a situation where they had to decide everything on their own.”

Tetyana spent a month in another region of Ukraine. Now she works mainly in the office in the center of Kyiv. People donʼt come to the memorial as often as before — in fact, while itʼs forbidden to hold mass events and visit the forests, it is empty. Earlier, more and more people came to the memorial every year. Now only single mushroom pickers come.

The only major event in six months was the visit of foreign ambassadors in May to honor the victims of political repression. They did not find the usual meetings of relatives buried in Bykivnya, did not see family photos and did not hear family stories, which they bring to the memorial. However, what they saw made a strong impression on them — at that time it was already known about the murders in Bucha, and a historical comparison was suggested.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»

And when, after the deoccupation of Kharkiv region, photos from Izyum appeared, Tetyana posted two eerily similar pictures on her Facebook page: a photo from the excavations of Bykivnya in the 2000s and from the exhumation of bodies from a mass grave in the forest near Izyum. Both showed the hands of the murdered woman tied behind her back. Neither the methods nor the performers have changed.

“As a person, I cannot get used to this, it causes a wave of rage and hatred towards enemies. But as a historian I can only say: whatʼs new?” says Tetyana. “Everything is the same: the same treatment of the locals, the same torture, abuse, looting. It was all already there.”

“Then why was it forgotten and impresses now so much?” I ask.

"We are a nation that has experienced a lot, but also developed," replies Tetyana. “Therefore, everyone was shocked that the neighbor did not change — the Russian army still operates with medieval methods. Russians preserved themselves, propaganda and the authorities found the worst features of the Russian national character and cultivated them. The Russian Maxim Gorky also wrote about the mentality of the population of the Horde and imperial type in the article Russian Cruelty. Propaganda grew these traits, nurtured them and set them free.”

“But at the same time,” Tetyana adds respectfully, “it seems to me that people were shocked by Russiaʼs behavior now, because they did not know and did not want to know history. The way itʼs taught at school cannot stand any criticism. And people in general tend to distance themselves from traumatic experiences and stories. So now people are in shock: they used to avoid traumatic topics, but now itʼs impossible: reality has fallen on their head.”

Translated from Ukrainian by Anton Semyzhenko.

Babel tells and will tell about all the crimes of Russians without a statute of limitations. Support us: via Patreon 🔸 [email protected]🔸donate in cryptocurrency🔸in Ukrainian hryvnia.

Alex Kuzmin / «Babel’»