1

"Mom is trying to hold on, sheʼs fighting actively. But dad just has no life now. A reburial could calm things down somehow”, says Roman Simonokʼs sister Olena in a telephone conversation. “I donʼt want to say this, but dad just might not make it. This should not be the case even in the most difficult times. Itʼs clear that now the living are more important, but one must also respect the dead. Roma was in Territorial Defense (TD) for five days, but for us heʼs a hero, for us he is the most important person. These are the people who protected us. For a day, two, a month — it doesnʼt matter. There should be respect. We need a place to come and remember."

Kharkiv Cemetery No. 18, or Bezlyudivske Cemetery, is located on the southern outskirts of the city, which was almost unscathed by shelling. There are several sectors here, one of which is the Alley of Glory, where dead Ukrainian soldiers are buried with all honors and under blue and yellow flags. There are dozens of such graves here. If to go deeper into the cemetery, there are fewer graves. On the freshest squares at the end of the cemetery, there are only mounds with signs: "unknown woman", "unknown man", "124", "remains of the body". This is how the graves of those who were not recognized or werenʼt sought by their relatives are signed.

Plaques on the mass grave.

Mykhailo Melnychenko / «Babel'»

There is a trench on the outskirts of the cemetery, the distance between the plates is no more than 10 centimeters. People were buried in it in bags, one of the trenches is still empty. Some of the plaques have a cross, plastic flowers or commemorative plates, but overall the square looks like a roughly plowed field.

On the left is one of the few hand-decorated graves. On the plate numbered 1417 — "Symonyuk R. S." Roman Simonok is buried here. On his grave are two plastic yellow roses, pink, purple and white asters in a glass and a few sprigs of wildflowers. His mother Alla brought them two days ago.

2

Usually, from April to October, the Simonok family moves to a country house in Pervomaisk near Kharkiv. Allaʼs parents built this house in the 1960s. She is now 73.

"We used to plant something here, and when we retired, we started coming just to have some rest," says Alla, a short woman with gray hair and freckles. “We put things in order after the winter. And our Romochka was in Kharkiv.”

Of the four rooms in the house, two are currently being used — one living room with a still-unheated stove and one bedroom, from where the news of the national marathon is broadcast on the radio. Alla asks not to take off my shoes and immediately offers breakfast. We decide to drink tea, and she almost guiltily explains why itʼs a tap water, the cleaner bottled is rarely available, and the remaining one is needed to drink medicine for her and her 72-year-old husband Serhiy.

"This is our falcon," says gray-bearded Serhiy, showing a photo on the wall. There is Roman in a uniform and with a weapon. “His last photo from the regional administration...” Serhiy feels it difficult to breathe, he blinks quickly, lowers his gaze and goes to make tea. When he returns, Alla is already talking about their life.

Photo of Roman Simonko from the Kharkiv Regional State Administration in his familyʼs home in Pervomaiske.

Mykhailo Melnychenko / «Babel'»

Alla was born in Pervomayske, then moved to Kharkiv. It was there that she met Serhiy — they worked together at an electrical equipment factory, it was a military enterprise.

"We worked for the defense industry," adds Serhiy, who was the chief mechanic. “For those missiles that Putin is now firing at us.”

They met in the factory dormitory and got an apartment nearby. Serhiy moved to Kharkiv after he was transferred from the Sevastopol Naval Academy due to poor eyesight. He himself comes from Vinnytsia, where his father, a Belarusian, went after exile in Siberia. He remembers the names of those he knew decades ago, willingly talks about his youth and passion for athletics.

"My great-uncle Simonok is a hero of the Soviet Union, there is a street in his honor in Sevastopol," Serhiy continues, bitterly pronouncing the name of the now-occupied city. “Oh, if our grandfathers stood up and looked at what they fought for...”

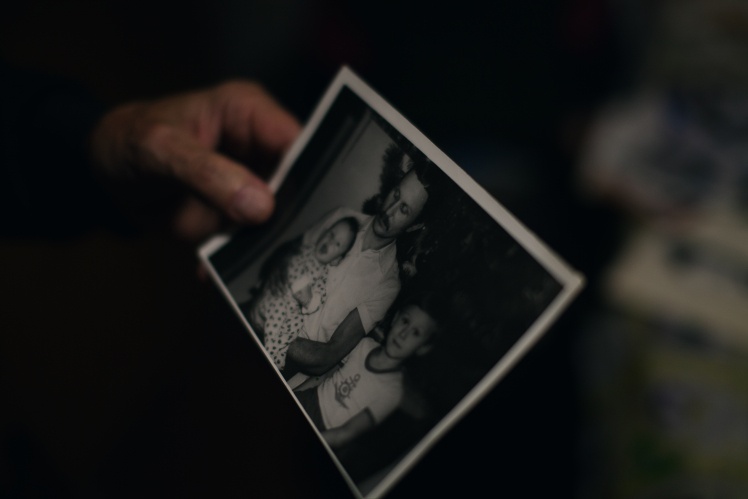

While Serhiy sighs, Alla takes out old photos neatly wrapped in cellophane.

Mykhailo Melnychenko / «Babel'»

“I took them from the apartment when shells started coming. I didnʼt know if we would come back," she says, spreading out the photos. On them, Roman is in a childʼs sailor suit, with a goulet on his forehead, at a New Yearʼs party, with his younger sister, against the background of Georgian mountains. There is almost no adult Roman in the pictures. “He didnʼt like to be photographed. Landscapes and buildings are there, but he is not. Now I ask his friends to send me pictures of him.

Roman worked as a construction worker, loved animals, wild flowers and hiking. He collected knives, knew small arms, was on the days of shootings on the Maidan, but did not want to become a soldier. Once a week or two, he went to see his girlfriend in Dnipro, often traveled to visit friends in Germany, and started repairs at home.

"Roma was a patriot, he burned for Ukraine," says Serhiy. “He said: ʼDonʼt be afraid of beasts, but be afraid of bad people.ʼ He was very modest, did not tolerate rudeness. Roma was a golden man.”

The photos end, and Alla comes across her wedding photos with Serhiy.

"I donʼt even know how they got here," she laughs. In the photo, she is 27, wearing a simple white dress, white gloves, and holding a bouquet of white feces. Nearby is 26-year-old Serhiy in a suit. “Thatʼs how long you and I, Alla, tolerate each other? 46 years old,” Serhiy laughs and looks at the picture. “There was a monument to Lenin, but we did not take a picture with it. And Derzhprom building is behind. It is on Freedom Square.”

Sergey and Alla.

Mykhailo Melnychenko / «Babel'»

“Just where Roma died,” adds Alla. Both fall silent.

3

On the morning of February 24, Roman entered his motherʼs room and said: "It has begun." He immediately went to the military commissariat, although his mother persuaded him to wait a little and understand what would happen next. It was not possible to sign up for Territorial Defense, so on February 26, Roman tried again. In the Kharkiv Regional State Administration, he was issued a weapon and assigned a post.

Territorial Defense was organized independently — there were no official lists, so the boys themselves appointed commanders and drew up the duty schedule. A separate district was assigned for each subdivision. Roman, together with ten other volunteers, were in the sixth subdivision of the Shevchenkivsky district.

"I think that without Territorial Defense Kharkiv could have been captured," says Oleksandr Aseev, Romanʼs brother.

He calls himself an "adult boy" — he is 70. He worked as a chief engineer in an office center, before that he was a deputy of the city council and head of the housing executive committee. Starting February 26, he began guarding the regional council building. He lived there on the first floor in one room with six teammates, among whom was Roman, five more lived in the next room.

At 7:45 AM, Roman called his mother to say that he was all right. In a few minutes, Alla heard an explosion and shouted into the already silenced receiver: "Roma!!!"

At eight oʼclock, when a Russian rocket hit the building, Roman was supposed to go to the security post instead of the night shift. What exactly he was doing at that moment isnʼt known for sure: four teammates who were with him died, one more was seriously wounded. Oleksandr was the only one left in the room almost unscathed.

Oleksandr Aseev, Romanʼs brother.

Mykhailo Melnychenko / «Babel'»

"We had lunch in the canteen, and for tea with sandwiches we went to 2-3 delivery points," says the man about that day. “One of them was near our room in the former locker room, we usually went there before the guard. The boys were getting ready to get to the post. I took tea in a paper cup a couple of minutes before eight and went back to the room to get the machine gun.

When Oleksandr was a few meters away from the room, an explosion rang out. He fell behind the column and saw what seemed to be hot balls flying around — it was glass illuminated by a flash. When Oleksandr woke up in a few minutes, he saw that the doors and windows had been blown away by the explosion. Near the room, one of the teammates was lying with a bloodied face. Alexander pulled him away, took his weapon and went outside. Another explosion rang out. The missile hit the part of the building where the room of the Territorial Defense was located. Not everyone managed to get out of it. Roma was among those who didnʼt.

On the same day, one living Territorial Defense soldier whose cry for help was heard by the rescuers and two bodies that Oleksandr recognized were found under the rubble.

"Rescue operations were stopped almost immediately," he says. “The city was under constant shelling, there were fires, destruction, I think the rescuers went to other objects where there were many people. The first of my boys was taken out of the rubble on March 17. It was our commander Volodymyr Gradusov.”

On the twenty-fifth of March, the dismantling of the rubble was finished. At the same time, Romanʼs body was retrieved and taken to the regional morgue.

The windows of the room where Roman probably died.

Mykhailo Melnychenko / «Babel'»

On the fourth of March, Oleksandr left Terrutirial Defense, and a month later he went to the west of the country — he received a concussion due to missile strikes. At that time, Territorial Defense was not officially registered, so neither Oleksandr nor the dead are considered participants in the hostilities.

Oleksandr had his own list of teammates, so when he returned to Kharkiv in May, he began to search for information about their graves and relatives. So he became the first to contact Romanʼs family.

"Other than me, no one was involved in this, although it is not difficult to do," says Oleksandr. “But no one knows anything about the boys, not only mine. I began to push the local authorities to legalize them as Territorial Defense, then the draft law 7322 appeared. These guys did not come because of summons, but because of the call of the heart. They deserve to be talked about as worthy Ukrainians. But, I think, nobody needs it here. In Mykolaiv, there was the same situation with the Regional State Administration, but the victims there were quickly legalized. And nobody does this in our region. I went to the deputy head of the administration, and he told me through an acquaintance that "now is not the time."

4

Until two oʼclock in the afternoon on March 1, Romanʼs phone received messages, but there was no answer.

“Why didnʼt they start digging them up right away? What if he was alive there? Didnʼt they have an equipment?... I suffer the most because of this and think about it all the time: maybe I could have saved him?...” asks Alla.

"I think he was alive," Serhiy adds, looking at the floor. “I had to run and call him to hear the call and pull him out. We would know where he is. I blame myself...”

Serhiy, Romanʼs father.

Mykhailo Melnychenko / «Babel'»

Alla and Serhiy repeatedly came to the Regional State Administration, looking for their son in civilian and military hospitals, in morgues at medical institutions. However, they couldnʼt find Roman there. The parents werenʼt told that the body had been found.

"We learned from the news that the rubble was dismantled," says Alla.

She realized that her son did not survive, and wanted to go to the morgue immediately. However, Serhiy got sick, and the couple waited. They arrived at the morgue on April 15. Allaʼs sonʼs body was never shown, although she asked for identification:

“They refused me allegedly because he was in a terrible condition, they told me to remember him as he was. But I would accept my child in any condition. Then I already thought: maybe he wasnʼt there or the bodies were so stacked that no one could be found there.”

Alla recognized Roman from the photo — she recognized his clothes and features, even though his face was dark from hematomas. Inga, the employee of the morgue began to convince that her institution would order a coffin and the burial would be "taken care of by the city", that there would be a separate grave behind the Walk of Fame in the military cemetery. Allegedly, it had to take 7-10 days. Romanʼs parents agreed, but in the evening they changed their mind and decided to bury their son themselves. The next day, April 16, Romanʼs friend started organizing the funeral and called the morgue.

“And we were told that he was already buried. Thatʼs how we found out about it,” says Alla. “Then I called to ask if he was buried. And they told me with such irritation: "You have already called!..."

The next day, the parents went to the cemetery to look for Romanʼs grave. It was not among the military graves. Alla called the director of the cemetery, and she explained that they should search in the remote 124th block. Alla with Serhiy and Romaʼs godmother, carrying bundles of wild flowers, walked to the other end of the cemetery. They reached the ditches, but there was still no grave. Alla called the director again, and she sent a cemetery worker to the family. He showed a grave-trench with a palisade of black tablets.

"I thought he," Alla lowers her voice and nods at Serhiy, "would lose consciousness." After the excavator, great depths of earth remained, and he began to rake them with his hands and pile them around Romaʼs grave, made a plateau inside, and we placed flowers on them. We sat in the park, came to our senses, went home — and did not speak at all for several days.

The family visited the cemetery several more times. There they were shown documents, which state that Roma was already on the list of "unclaimed" from the morgue on April 12. He was also listed on April 16, that is, after the family recognized the body and asked to bury it themselves.

Alla and Serhiy began to demand a reburial, the woman contacted the communal enterprise Ritual, which organized the burial on behalf of the city.

“Lyudmyla Konovalova, deputy director, said: ʼFind some kind of cross there and put it up.ʼ But I donʼt need a cross from someone elseʼs grave! Roma was not a believer at all,” — resents Alla.

"Roma did not criticize people who believe, but he was a pure materialist," Serhiy adds. “If we are going to put up a monument, then of course there will be a cross on the obelisk in the corner. But he and I never talked about the burial.”

A plaque on Romanʼs grave with an incorrect signature.

Mykhailo Melnychenko / «Babel'»

In the end, Ritual brought the grave to order. However, the reburial was first refused, and then, allegedly due to sanitary regulations, which are not specified anywhere, the authorities said that the body can be reburied only after three years. Already in September, they assured that the bories will be reburied in winter, when the temperature will be low enough. The Kharkiv City Council also promised to help, but nothing has changed. Alla was given a piece of paper with a list of documents that needed to be collected, but was told not to do it yet as they might become outdated. That woman doubts whether her son will be reburied at all.

“Or maybe they just donʼt want a reburial, because heʼs not really there? Those plates were just stuck there. But there must be a number on the bag. Thatʼs why I said that digging can only be done in my presence.”

5

Of Romanʼs belongings, the family was given only a passport with drops of his blood — neither the phone nor the knife, which were always with him, were returned. Alla was hinted that everything was taken by marauders.

In six months, Serhiy lost almost 10 kilograms, and both his and Allaʼs right hands get numb. She cries at night so he doesnʼt see.

"Of course, those were hot days [in the beginning of the invasion]," Serhiy says. “We had 1% of hope, but a person still lives by hope. Of course, who wonʼt suffer for their child? Of course, this is war. But I knew why my son died, he honestly went to defend his homeland. But it was what happened next that killed us. We survived one tragedy, but not the other...”

***

Already after our meeting with the Simonok family, on September 19, Kharkiv Mayor Igor Terekhov announced at a meeting that after an official investigation, it was found that Roman was buried in violation of the law and will soon be reburied with military honors as a defender of the city.

Translated from Ukrainian by Anton Semyzhenko.

Babel tells about how we all live through this war. Support us: Patreon 🔸 [email protected]🔸donate in cryptocurrency🔸in hryvnia.