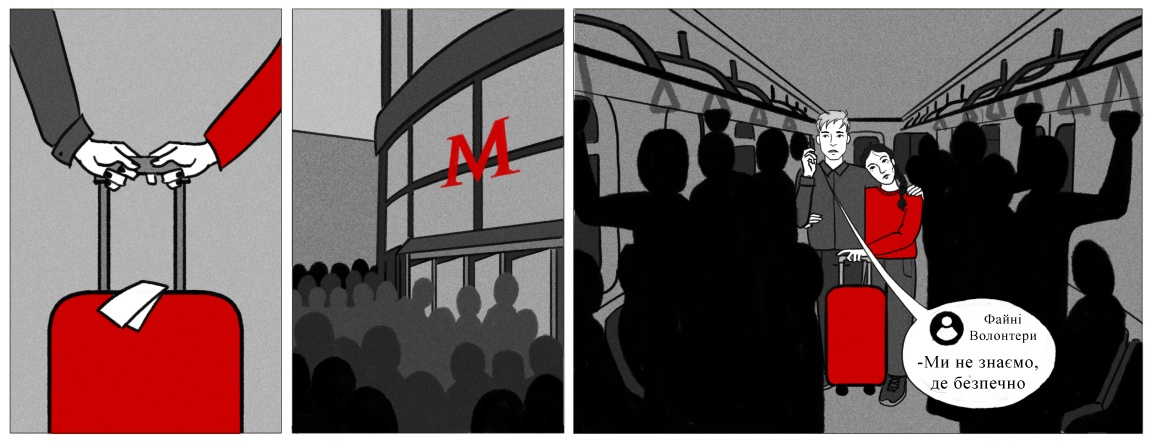

Roma: A few months before the war, friends from Poland wrote me that Russia was going to attack Ukraine. Later, friends from Israel wrote about it. But instead of listening to their words, we said, "Donʼt escalate, nothing will happen." I did not believe in this. On the evening of February 23, I sat and flipped through the Facebook feed and read that the attack would take place within 48 hours. I was very scared, Anya came home, calmed me down and we started to collect our stuff. It was about 3 am. We monitored train tickets, it was hard to understand anything, my hands were shaking, but we managed to get tickets to Lviv. A plan was already there, we focused on picking things up. Then we heard several explosions, and everything inside got cold. We understood: the war began. We heard that there would be an attack on Kyiv, took tickets, packed up an "emergency backpack" and ran out. There were people around, everyone was running away, panicking. We went down to the subway. We called the volunteer organization in Lviv, and they told us: “We donʼt know where it is safer now, we also have an air alarm, and we also hear explosions. This is the common situation all over Ukraine." Anyaʼs father lives near Kyiv and her mother is in the city. We decided to get together and wait [for the hostilities to pass] in the village.

Anya: We thought: “Kyiv is the most important, and nobody needs Kyiv Oblast. We will go to the village 50 km from Kyiv and wait there, and then we will come back”.

Roma: We returned home from the metro station. It seemed that they [the Russians] were coming from all sides and it was unclear where to go. We decided to go to the metro to pick up my mother, agreed to meet at the last station —Akademmistechko, and from there my father would pick us up in his car. At the Shulyavska station they said: "Get out, the train doesnʼt go any further." So we went by foot. Roads were clogged with cars, and people were driving, walking, both in civilian clothes and military uniforms. My father arrived, we got in the car and headed to the village in the north of the oblast. The first day I wrote to my sister, who lives near Moscow: "We have a complete nightmare here, come out, talk about it!". She replied they [the Russians] were targeting only "strategic objects" and hung up.

In the village it was like this: our houses, and across the road a golf club with a six-meter fence. Russian soldiers stood there and fired from there. Their machinery was so loud that it seemed they were going to hit us.

Anya: On the third day the electricity went off. By the way, an interesting observation. While there still was electricity, everyone were flipping through their phones or watching TV. And when the power went out, we had to do something — and we started talking. I realized how little we communicate in ordinary life. During this period, I learned more about my parents than in my entire life.

And then the cellular connection disappeared. Our relative said that if there was no connection, it meant that something would happen, and we had to go to the cellar. We, six people and two dogs hid in the basement behind the house. At first, there was noise: everything is trembling, we are trembling and the cellar is trembling. I said goodbye to life, I thought the shell would hit our basement. We stayed there one day, then two, then three — we only went out to eat and go to the toilet.

Roma: We dug a hole in the ground and went to the toilet there. In the first days, we bought canned food. One late night in the cellar there was a knock on the door. We froze, we thought they had come to kill us. I still donʼt know what it was, maybe a dog?

Anya: At first it was very scary from the noise and shots, but then we got used to it. There are shells in the sky, and we sit in the cellar, reading books.

Roma: We sat without communication, but the news reached us. Someone had a generator. Someone came and told us the news. One old man, Lukych, 80 years old, fearless, walked through the village, to the [Russian] checkpoint, looked, and then retold everything. When the gas was turned off, we started cooking in the oven. Later there were rumors that there was no gasoline, but my dad managed to refuel his old Tavria car. Meanwhile, the Russians rushed to the electric cars in the golf club and began to ride on them. If the car broke down, they kicked and shot it.

Anya: At first we accused ourselves of being in the occupation, that we had to leave. Then I thought: we need to get out, but how to do it? We saw that the neighbors were leaving. We also decided to go. But my father forbade and said that the Russians shoot people.

Then we realized that he was right: some [of those who tried to escape] survived, some didnʼt, and some were shot.

Roma: One day we learned that Russians are already walking around the village. They behaved as hosts.

Anya: They called themselves saviors. They went from house to house in the village, but they didnʼt reach us. Later, apparently, someone betrayed us, maybe one of the locals, maybe they threatened and forced us with a machine gun.

Roma: The first time we ran away and hid behind the house. I then accused myself of leaving Anya and her mother in one place and running to another. I began to consider myself a coward, but Anya comforted me: "You are a man — they will look for you first."

One day Russian soldiers came into the house and said, "Letʼs get acquainted."

Anya: Four people came into the house, Buryats, all with machine guns. Dad told us to hide, and he would come out and figure it out by himself. He talked to the soldiers and then ordered us to go out. They would find us anyway. It was scary, as you donʼt understand how to behave.

Roma: They looked at our phones. We uncharged the batteries in the phones. While there was electricity, we removed all messenger apps. I thought that if they saw that there was no SIM card in the phone, it would be suspicious, so I left one of the cards. Dad found an old push-button phone. Sometimes there was a mobile connection, but we did not contact anyone. We thought they will notice the activity and there will be questions to us. But someone called near our area, and they saw the call [on their radioelectronic hardware].

Anya: For a few days they just came in and even asked, “Maybe you need something? Any products?” We replied that we had everything The first thing they asked was if we had vodka.

Roma: Even when there was a connection, we read in some public how to behave oneself with the occupiers. We answered "Yes", "Ok", "we donʼt need anything", as peacefully as possible. In a sense, you canʼt say, "We donʼt need anything from you, bitches." They are really always interested in vodka. We had no vodka in the house, but they found it somewhere. Most likely, the local alcoholic who betrayed us told them where the vodka was and set a relationship with them so that they would not touch him.

Roma: Once they came back, drunk, they said that someone was calling from our area. We were taken to a house and interrogated. Anyaʼs father said he called, but they didnʼt believe it. And after that [the Russian military] said: "So, no one confesses? Then get in line.”

Anya: On the one hand, he was very sorry for behaving like that, causing us pain and suffering. On the other hand, he said that we should be taught. There was a contract — both good and bad cop in one. He also said that he was from an orphanage.

Roma: He took off the fuse, just clicked them — queue or single, queue or single.

Anya: He interrogated us for three hours. This Buryat is 21 years old, he was their chief, the rest were pawns. But there was another one, saying all the time: "Iʼm ready to shoot everyone, I like it, Iʼm having fun, Iʼm covering up my childhood traumas."

Roma: Interrogation is torture, itʼs scary. When he realized that nothing would come of us, he put us back to back and said, "I donʼt want to waste ammunition, Iʼm going to kill you all with one shot." He said something, turned the machine gun in his hands, then said that he needed to sleep because he was "boozy". He took us to the room where the stove was: "Letʼs shoot you here so there wonʼt be much noise." But then he took me out into the kitchen again. He fired at the ceiling and repeated that we needed to be "taught", and added: "I came today as a teacher, and tomorrow I can come as an executioner." The next day they arrived and asked to show Anyaʼs phone. They clung to the date — they show Anya the phone and say: “You called Dad on the 26th. Who is Dad? ” Although it was not in March, in February. Anya gave access to her phone, there were our home photos, videos, and intimate photos just for herself.

Anya: One of the next days they came in and told everyone to line up. Got the phone.

"Whose phone?" — they ask.

"My phone," I said.

"Come with me for questioning."

I didnʼt know if I would come back or not. But I understood that I would not be able to give up and would have to leave. They put a hat on my head so that I could not see anything, put me in a car, which they took from my dad, and took me to one of the neighboring houses. They put me to bed. I was left alone.

"Undress," he ordered.

"How many of you will be?" I asked.

"I will be alone," he replied. "Do you want us to be many?"

"No, can you be alone?" I answered.

"Well, look, — he said, — and then here in the next room guys, they want too."

In general, I coped with it. The next day it was tougher. It was and was forgotten. But when I came and saw the condition of all my loved ones — it was really scary. I have never seen such faces. They did not know whether I would return or not, what was wrong with me, they were terribly worried.

Roma: For the first time they were gone for maybe an hour and a half. Anyaʼs father had heartache. He tried to calm everyone down. Anya behaved calmly, she only told at night what happened to her. And the next day [the Russian military] brought a psychologist with him. Comrade. With wine. They took Anya for four hours.

Anya: I didnʼt want to tell anyone [about it] at all, but I had to share it with someone. I couldnʼt tell my parents, especially my dad. I said we just talked. The worst thing is when I saw my dad, who couldnʼt speak, couldnʼt say a word, his legs were crooked, and he lost consciousness, all in tears. It was very scary.

Roma: [Russian soldiers] have always wondered why people live so well. We sincerely wondered why we do not want to go to Russia. Many times asked about it. And they have this rule — the war will write off everything. You can do anything. One day we got together, got in the car and drove in four cars with the neighbors. We went to Makariv. They started firing with machine guns. We rode and prayed. We prayed all the way to Zhytomyr.

Anya: And our neighbor, who was behind the wheel, said: "Pray louder." We were under occupation for 35 days. But when we came out — we realized, we might have been in the worst situation. We arrived in Uzhhorod and I thought that when God saved me, it was probably necessary, we can not sit idle and rejoice that I was saved, but we must do something to help others. But Iʼm constantly shaking, Iʼm crying, Iʼm hysterical, I canʼt do anything with myself, I donʼt understand whatʼs going on. I donʼt understand why I survived, and those children, women, men didnʼt survive.

Roma: We understand that in such circumstances it does not matter what and how you earn for a living. Fuck all these statuses. How you came into this world, what you learned in your life — these are important things. And all these wrappers that you have — they are nothing, what are you going to do with them?

Anya: And [Russian soldiers] kept saying that Ukraine is worse than Syria. And they were drunk every day. They were still talking in unison, and to us: “Are you not even swearing? You speak Russian so well." We really speak better than them, it was difficult for them to express their opinions. Their chief was from Chita, the rest — from Buryatia. One of them even scolded Putin, saying, "Asshole, he started all this, nobody needs it." They admitted that they had come to the war to earn money.

Roma: They also said that they have many non-gasified villages and cities, while gas, like wood, goes to China. But they are supporting Russia. That is, they say that Putin is a dickhead, and then immediately: "But we will kick your ass.”