Nazi lawyers in Germany

In 1987, German lawyer Ingo Müller published a book Terrible Lawyers, in which he expressed the view that the judiciary of the Third Reich and its staff had received almost no punishment since 1945. The trial of Nazi judges took place in 1947 and is part of the Small Nuremberg Trials — 12 trials that took place after the main tribunal. Sixteen German lawyers involved in the repressions were tried. Ten were sentenced to various terms in prison, four were acquitted, one was released on medical grounds, and another committed suicide. Also, 39 judges of the Imperial Court in Leipzig were sent to Soviet prisons, most of whom died.

However, Ingo Mueller believes that in fact, "racial laws" and other repressive norms of the totalitarian regime were used by hundreds of lawyers throughout Germany. And none of them was responsible for it. According to Mueller, most of them never admitted their guilt because they "just obeyed the law." This was one of the reasons why the Nuremberg tribunal was international — the victorious countries did not trust the local German courts. And Israel and international Nazi hunters, such as Simon Wiesenthal, believed that war criminals could not be tried by German courts even many years after the war.

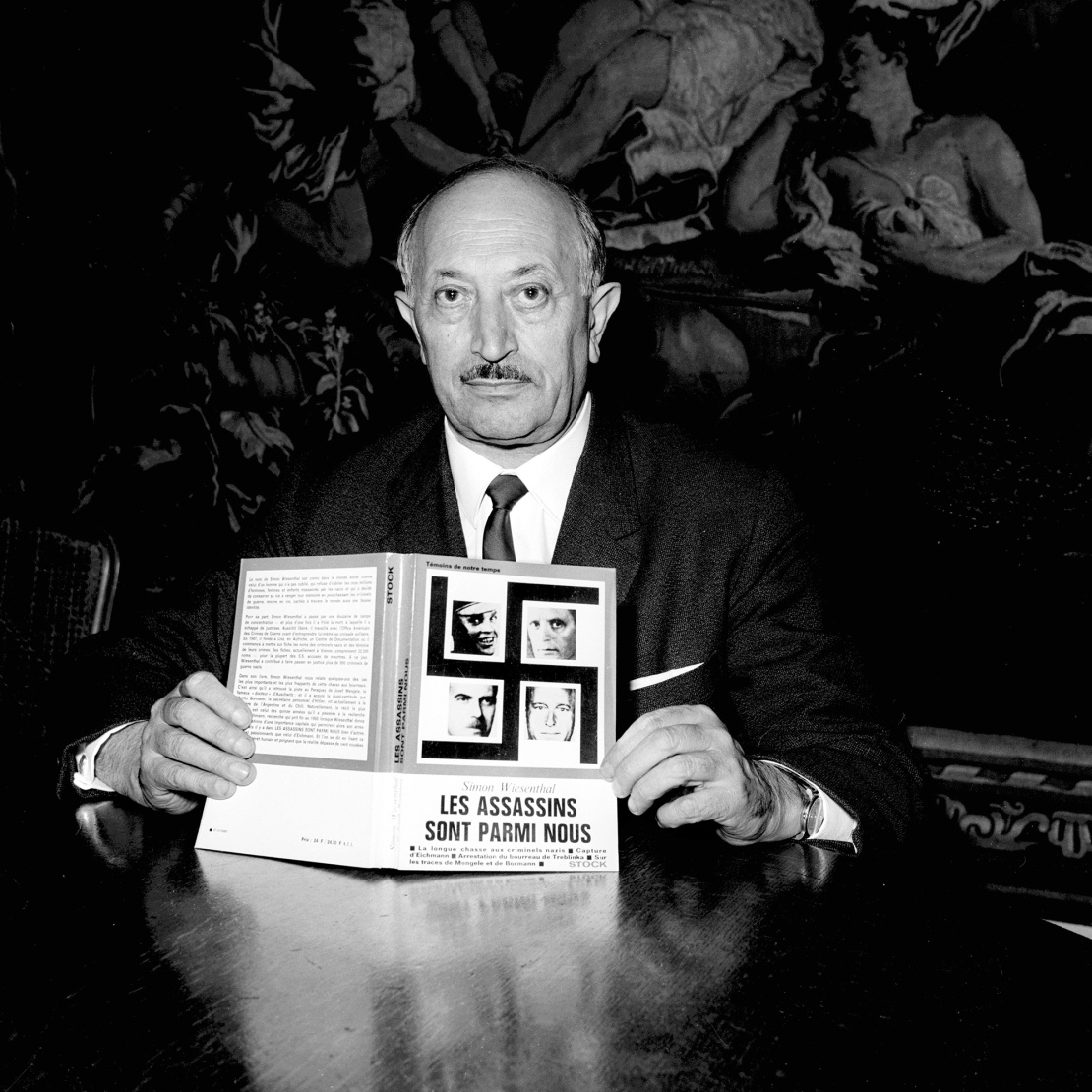

Simon Wiesenthal shows his book Murderers Among Us, October 3, 1967.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Hans Globke became a symbol of the inviolability of former Nazi lawyers. He was State Secretary of the Chancellery of Federal Chancellor Konrad Adenauer from 1953 to 1963. Although in the 1930s, Globke was one of the leading authors of "racial laws" and legalized repression against Jews and other peoples whom the Nazis considered "racially inferior". At the same time, he was never a member of the NSDAP, so it was not possible to formally prosecute him as a Nazi criminal. So Globke was simply left alone, and in the early 1950s Adenauer invited him to the government. And it was only after the chancellor himself retired that Globke retired from big politics.

Mueller notes that after 1949, no trial of former Nazis took place in Germany for almost ten years, although there were statements and lawsuits from victims of the totalitarian regime. The first such trial was in Ulm in 1958: ten SS men were charged with the murder of 5,502 Jews at the Lithuanian border and sentenced to between 3 and 15 years in prison. Most of these trials in Germany took place only under pressure from activists and the press.

Hans Globke

Wikimedia

Nina Gladitz vs. Leni Riefenstahl

Director and actress Leni Riefenstahl met Adolf Hitler before he came to power. And this happened at her own free will. She wrote a letter to Hitler in May 1932, impressed by his campaign speeches. He agreed to meet the young director, who has just released her first film, the mystical drama Blue Light.

Since then, Riefenstahl has been a frequent guest at various Nazi events. Even before 1933, she was already acquainted with Hermann Goering and Joseph Goebbels. And when Hitler finally came to power, Lenі immediately began making completely different movies. During 1933-1935 she published her propaganda trilogy on the congresses of the NSDAP — Victory of Faith, Triumph of Freedom, and Freedom Day — our Wehrmacht. Then Riefenstahl made Olympia — a film about the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin.

In 1940, Riefenstahl began filming The Lowland, aт adaptation of Eugene dʼAlbertʼs 1903 opera, which Hitler loved. She used 120 Roma and Sinti concentration camp prisoners from Maxlan and Marzan camps. Hitler allocated money for the film from the party box office.

Due to the war, Riefenstahl didnʼt manage to finish the editing of The Lowland. In April 1945, she was arrested by the Americans. She spent several months in prison and until 1947 was almost constantly under house arrest, interrogated and tried several times. In court, she said she knew nothing about death camps and other Nazi crimes, and called her propaganda films purely documentary. Riefenstahl admitted that she was under Hitlerʼs influence, but did not commit any crimes and admits her mistake.

Leni Riefenstahl and cinematographer Sepp Algeier are filming The Triumph of Freedom on the streets of Nuremberg during the 1934 Nazi Party Congress.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

And she was believed. Leni Riefenstahl managed to keep her reputation in the film world. No one gave her budgets like Hitler anymore, so she switched from film to photography. But in 1954, The Lowland was released, which had to be re-edited, because part of the film has disappeared during this time. German film critics praised the film. Leni Riefenstahl has taken a niche in the history of German and world cinema, and no one has spoken publicly about her collaboration with the Nazis.

In 1982, the documentary Time of Silence and Darkness directed by Nina Gladitz was released on German television. It described in detail the story of the Roma and Sinti in the making of The Lowland. Gladitz found one of the participants in shootings — Josef Reinhardt. He said Riefenstahl personally traveled to concentration camps to select prisoners. During the filming, they lived in almost the same conditions as in the camp, they werenʼt paid anything, although there were agreements about it. Also, they were punished for any mistakes they made, sometimes beaten. Moreover, Reinhardt claimed that Riefenstahl promised to help the prisoners leave the death camps and avoid extermination, but did not keep her promise. Most of those who were used for the shootings died in Auschwitz.

Gladitzʼs original idea was to involve Riefenstahl in a dialogue with Reinhardt and to make a "face-to-face meeting". But Leni did not respond to this proposal, and after the release of the film sued for defamation. The German court made an ambiguous decision: it managed to prove the fact that Riefenstahl really went to the camps and saw what was happening there. But the court failed to prove that she promised the prisoners freedom. So Gladitz was urged to cut this episode from the film. She refused, and Time of Silence and Darkness was effectively banned.

Leni Riefenstahl denies allegations that she used concentration camp prisoners as extras for her film.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

After that, the fight with Leni Riefenstahl became a matter of life for Nina Gladitz. Germanyʼs film and television circles supported Riefenstahl in this dispute, so Gladitz was in disgrace — no one gave her budgets or ordered documentaries from her. For another 30 years, she gathered information, searched for documents and memoirs, testified, and interviewed people who had worked with Leni in the 1930s. And in 2020 she published the book Leni Riefenstahl: The Career of a Criminal, in which she argued that Riefenstahl knew a lot about the crimes of the Nazi regime and cooperated with it quite consciously.

Even in the 21st century, it has been difficult to publish such a book — the influence of Riefenstahlʼs personality in Germany is still significant. About 30 publishers refused to publish Gladitz, and she spent four years looking for opportunities to publish the book. Even though Leni Riefenstahl herself died in 2003, having released her last film Underwater Impressions a year earlier. Nina Gladitz died in 2021.

Mascha Kaléko vs. Hans Egon Holthusen

Mascha Kaléko was a German poetess of Jewish descent. She was born in 1907 in Poland, and in 1914 her family moved to Germany. Kaléko wrote poetry in German and has been published in the Vossische Zeitung and Berliner Tageblatt since 1929. In 1933 she published the first collection of poetry, which immediately had to be edited due to Nazi censorship. In 1938, when repression against Jews intensified, Kaléko managed to travel from Germany to the United States. There she continued to publish poetry collections in German.

In 1956, Mascha Kaléko returned to Germany. In 1959, she was to receive the Theodor Fontani Literary Prize from the Berlin Academy of Arts. It turned out that among the members of the jury was a German poet and writer Hans Egon Holthusen, moreover, it was he who oversaw the poetic direction of the jury. Holthusen joined the SS in 1933 and became a member of the NSDAP in 1937. During World War II, he fought in the SS. After the war he continued to live in Germany and became a respected poet and literary critic.

Mascha Kaléko, Austria, 1932.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Mascha Kaléko refused to receive the award from his hands. But Holthusenʼs influence in literary circles was too great, the scandal never came to light, and Kaléko became an undesirable poetess in Germany. That same year she had to emigrate to Israel. She continued to write poetry in German.

After 1960, Hans Egon Holthusen went to the United States to become a professor at Northwestern University in Illinois. Then he returned to Germany, where from 1968 to 1974 he headed the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts. He died in 1997.

Former Nazis in the GDR

The German Democratic Republic, established in the Soviet-occupied zone in 1949, officially claimed that it had defeated Nazism on its territory. Even more, official Soviet and East German propaganda shifted responsibility for all Nazi crimes to West Germany. The Berlin Wall that divided the capital was called Anti-Fascist Defensive Wall by the propaganda, meaning that this wall protects denazified Berliners from the Nazis, who allegedly still rule the rest of the country. The suppressed uprising against the pro-Soviet regime in East Berlin in 1953 was officially considered a "fascist coup."

At the same time, the situation with former Nazis in the GDR was almost the same as in Germany. For example, according to modern research, after 1949, 14% of police officers in East Berlin were former Nazis. The Stasi knew about almost all former members of the NSDAP and the SS, but was in no hurry to catch and judge them. Information about the past of these people was used for blackmail — the former Nazis could be used as agents and informants. Even when a war crimes case went to court, it was held behind closed doors. Because officially there could be no Nazis in the GDR.

Parade on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the construction of the so-called Anti-Fascist Defense Wall, August 13, 1986.

Wikimedia

In total, from 1949 to 1990, only 15 trials were conducted in the GDR against criminals from "death camps". Two persons were shot, three were sentenced to life imprisonment, and others were acquitted.

Among the freelancers of the Stasi were also former Nazis, whose skills were useful to the German Chekists;. All that was required of them was to pledge allegiance to the new socialist regime. Historian Heinrich Leide, who worked with the Stasi archives, published a book in 2005 titled Nazi Criminals and State Security: The Secret Policy of the GDR. In it, he described the fate of, for example, the organizer of the anti-Semitic pogroms in Paris in 1941, SS officer Hans Sommer. Taking advantage of his past in the SS, he gained trust from far-right organizations and politicians in Germany and Italy, and then passed on information to the Stasi. Another well-known Stasi agent was Josef Settnik, a Gestapo officer and Auschwitz war criminal who was to be executed in 1964 but was protected by the Stasi.

After the unification of the country in 1990, the process of decommunization of East Germany began. But attempts to convict the Stasi for their crimes ran into the same problem that Ingo Mueller wrote about the Nazis: German courts tried not to prosecute under the new law people who acted according to the old. Communist activists and German Chekists worked under the laws of the GDR, so it was difficult to judge them under the laws of the new Germany. Of the 91 thousand employees and 300 thousand Stasi agents, only two or three hundred were convicted, none of whom spent more than 12 years in prison.

Translated from Ukrainian by Anton Semyzhenko.

Support Babel:🔸donate in hryvnia 🔸in cryptocurrency 🔸via PayPal: [email protected].