1.

In the evening of April 25, I received a message from military doctor Vsevolod Steblyuk. "Hello, I forgot about your experience in the morgue. In Bucha, hands and help are very much needed. If you want — call this number, Alyona will answer you." I call and ask what to do. Alyona explains: to help unload refrigerators with the corpses of locals killed by Russian soldiers during the occupation, describe them and make lists. I agree, we set the meeting at 7 am in Pechersk district in central Kyiv.

Steblyuk arrives by ambulance car. It was bought and driven from Denmark. Vsevolod in olive uniform with shoulder straps, keeps a holster with a pistol on his thigh, glasses on his nose. He laughs and claps at the wheel.

— Volunteers gave it [the car] to me. All the salary goes to care about my "ambulance". The oil must already be changed.

Seva looks at my white Nike and laughs.

— You shouldnʼt have taken these sneakers: in the refrigerators, there are body remains and blood. Youʼll get dirty.

— I have no other shoes, — I answer. — And I donʼt care.

Vsevolod Steblyuk.

Steblyuk has been a practicing doctor for 30 years, taught at the Academy of Internal Affairs, and now serves in the National Guard. For the last few days he has been helping to dismantle the bodies of the locals killed in the Bucha morgue. I ask what is being done with the bodies of the killed Russian soldiers.

— Oh, nobody does anything with them, — says Steblyuk, — They donʼt occupy place in our morgue. They lie in the woods and thatʼs it. All sorts of Buryats there, tankers or reindeer herders, who knows who they are there.

In fact, the bodies of Russians are also collected. Unlike the occupiers, Ukraine clearly adheres to the norms of international humanitarian law. But it is not the Bucha morgue that is dealing with these corpses — the Military Prosecutorʼs Office takes care of them.

We are going to pick up Alyona, "a fighting friend from the days of the Maidan," as Steblyuk says. She is also a physician. Alyona writes the names, surnames, dates of birth of local bodies found in Bucha, and maintains the database. She looks sleepy and very tired.

— I thought I was off today, — she says. — If Spirin is going too, I can sleep. In fact, though, I canʼt.

We turn on the beacon lights and go around the traffic jam near the checkpoint on the way out of Kyiv, then follow the Ring Road. Steblyuk points his finger somewhere on the roadside.

— Here in the 90ʼs the best grilled chickens in Kyiv were sold. Everyone came here: bandits, police, businessmen. And we had a hand-to-hand fight club nearby. We made a sauna there. And one day a bugor came and said to his guard: "Go to the Ring Roaf and bring chickens." They left and in an hour returned with a prostitute, saying "sorry, there was only one chick.”

«Babel'»

We go towards Irpin. The war meets us at the entrance to the city with burned houses, collapsed roofs of the supermarket, fallen poles. The destroyed equipment was removed already, but there is still a baby carriage near the blown up bridge. The photo, where people are hiding under this bridge from the shelling of the Russian army during the evacuation, seems to have flown all over the world. We are going faster than necessary, Steblyuk shouts to the colleague:

— Alyona! I want to go to the summer camp. Donʼt you mind?

— As you say.

We arrive in the center of Bucha town, take a turn near Novus supermarket, where a few weeks ago the remains of the Russian uniform lay. Fierce fighting took place on this street, leaving dozens of Russian tanks, soldiersʼ corpses, their food rations and clothes. In a few minutes the car stops near a fence.

— I spent my childhood in this camp, — Seva says. — Then I became counselor, then even a senior counselor." Then my son spent summers here. This year I wanted to send my grandson here. But Russian soldiers made a base In this camp, dug everything around, and set up a torture chamber for Ukrainian veterans in one of the buildings. They were tortured and shot there.

Steblyuk in a camp where Russian military tortured and shot Ukrainian captives.

We enter the territory. Itʼs warm outside, birds are singing, the ground is dug, food wrappers are lying everywhere. Steblyuk takes out his phone to take some photos, but soon hides it.

— Oh, I donʼt want to. Just canʼt. It seems they have destroyed the best part of my life, my youth and my childhood.

Alyona tries to calm him down: she says that the camp is intact, the buildings are standing, and someday the children will have fun here again.

— Nothing will ever be here again, — replies Seva. — They ruined everything.

We get in the car and go to Polyova Street, 19. There is a clinic, followed by a morgue. The bodies of all the inhabitants killed by the Russian military are brought here.

2.

People are crowding in front of the tent near the one-story morgue building. This is an information center. Inside there are paper tables, a tablet and stacks of paper. Volunteers make lists of those killed, and relatives come to the tent to look for their parents, mothers, sons, daughters, or grandparents who died during the occupation. At 9 oʼclock in the morning, there are already 6 people at the tent. An elderly man in a gray suit and cap tries to find his son. He takes a few sheets with lists, puts his glasses on, and reads the names closely.

— Denysov. Denysov. Denysov is on "D". Where can he be? Iʼve been looking for him since March 3 and canʼt find. He disappeared in late February, stopped communicating, and a neighbor said he had been shot by Russians, — says the man.

Alyona puts her hand on the manʼs shoulder.

— Donʼt get nervous, he will be found.

«Babel'»

The man takes other papers with lists and continues searching. He is gently pushed by a guy who introduced himself as Ihor.

— My relative was buried by a neighbor somewhere in the woods. He stuck a Christmas tree branch in the grave, — says Ihor. — The neighbour says she lay on the street for three days, he couldnʼt stand it and buried her. But he canʼt remember where exactly. So now I go to the morgue every day, just in case they dug the grave up and brought her.

Steblyuk calls into the ambulance car, itʼs time to change into special rubber overalls.

— But today we have only one refrigerator, — says Seva and points to a huge truck, — There are 30 people, we can do it quickly.

I put on overalls, gloves, then another gloves — the first pair will break quickly — and a polyethylene apron on top. Steblyuk passes me a respirator.

— Thank you, Iʼm used to it, I donʼt need it, — I reply.

— Youʼre used to it at home, itʼs not at home here, — Steblyuk replies, and I take the mask.

The morgue yard is small and oblong. Near the information center is the King funeral home, coffins and funeral wreaths can be seen in the window. On the left is a refrigerator truck with the inscription Thermo King, in 20 meters — another one, also with corpses. A policeman walks nervously next to it.

— Yes, fuck, yesterday they put the diesel in, it seemed to work, — the policeman shouts into the phone, — And today it stopped cooling.

Steblyuk explains that one of the refrigerators broke. We need to get the corpses out of it and transfer them to the other refrigerator truck that works. My face under the mask immediately begins to sweat. Fingers get wet. Two people in the same clothes stand near the refrigerator. Fleece sweaters, protective pants and caps with flags of Ukraine and the United States. These are volunteers from USA. I approach them and give them gloves.

«Babel'»

— Hi, Iʼm Wade, from the United States, — says one American. — Itʼs a nice day today.

— Hello! Iʼm Eugene, I studied in Boston, — I reply.

— Great! Have you seen Bill Gatesʼ yacht? — says Wade. — It stands in Boston and looks like the yachts of Russian oligarchs.

— I didnʼt have a chance, — I say, picking up an iron trolley for the corpses. There are hair on it, dried blood and traces of a mass that is difficult to describe, which is left behind by human remains.

Policeman Bohdan puts a vegetable container near the truck and jumps inside. On the floor near one wall there are bags with bodies, near the other — bags with charred bodiesʼ remains. These are the residents of Bucha, whom the Russians tried to burn when they were leaving the city. Bohdan grunts and pulls the first bag. We grab it by the plastic handles and pull onto the trolley. Bohdan is in command.

— Take this one to the back entrance of the morgue.

Alyona takes out a sheet of paper and writes down the data: "__ __ Oleksandrovych, June 5, 1977, found in Irpin, Antonov Street _ \ _". We wait until she writes everything down, and take the trolley to the morgue. The zipper on the bag broke, the corpse is very rotten, the skin peeled off and mixed with the sweater, there is a white bandage on the manʼs left arm. Before the assassination, Russian soldiers tied his hands.

— Wade, — I ask. — What are you doing in Bucha?

— I move corpses, — the guy answers.

A forensic expert is smoking near the back entrance to the morgue. There are 8 trolleys with corpses, and some empty ones. We leave the trolley with the body and take an empty one. The expert spits.

— Guys, I canʼt cut more than 11 corpses today. Bring me three more and put the rest in the refrigerator.

We return to the truck. Steblyuk and the other American roll another trolley in out direction. We approach the refrigerator. Bohdan disappears again in the darkness and barely pulls out another bag with the body.

«Babel'»

— This one is heavy, be careful, — he says and pushes the bag up to the edge of the truck.

We grab the plastic handles again, I rest my sneakers on the trolley, and my partner and I pull the body together. The zipper unzips on the bag, blood splashes directly from it on Derrekʼs jacket. “Oh fuck,” he says softly, but doesnʼt even raise an eyebrow. Alyona writes: "An unknown corpse with an eagle tattoo on his left chest." We take the trolley and bring it to the morgue. The procedure is repeated several times.

People gather near the central entrance to the morgue. Paramedics take out a coffin and wreaths. Someone carries the flag of Ukraine and a portrait of a murdered local resident, recognized and ready for the funeral. Foreign journalists walk around — several TV crews. One of the journalists pokes a microphone with a long stick on my face.

«Babel'»

— Tell me, how do you feel now?

— I feel that you are an asshole, — I say while trying to wipe the sweat from my forehead without getting smeared with blood.

Steblyuk and Alyona are already in the second refrigerator, the working one. Today, the morgue no longer accepts corpses, so now the main task is to move the remaining bodies from a non-working refrigerator. In half an hour we transfer about 10 of them. After that Bohdan leans against a refrigerator wall.

— There are two more on the trolley, — he says. — And a few bags of coal. These are the ones they tried to burn.

We get first one bag with the body, and then another. Everything is mashed inside it: the corpse is rotten. We put "coal" on top. Inside these bags the remains of the bodies are mixed. We take it all to the second refrigerator. Steblyuk commands:

— You can take off your overalls and gloves, thatʼs all for today.

I take my gloves off and, finally, my respirator. I unzip my overalls, take out cigarettes, light a lighter and then a cigarette. The coffin is carried past. A woman with light pink hair grabs my shoulder.

— Iʼm sorry, Iʼm looking for my daughter. She appears to have been shot on March 5 or 7 and buried in a mass grave.

— Go to the tent. Volunteers there will help you and give the lists, — I answer.

Steblyuk removes overalls on the go. He doesnʼt seem to be very happy with himself: we did all the work quickly, all we had to do now was to transfer names and surnames from sheets of paper to a Google document.

— Here in the cafeterium they feed very well, — says Seva. — So you decide for yourself, but Iʼll wait until lunch.

Itʼs almost noon.

3.

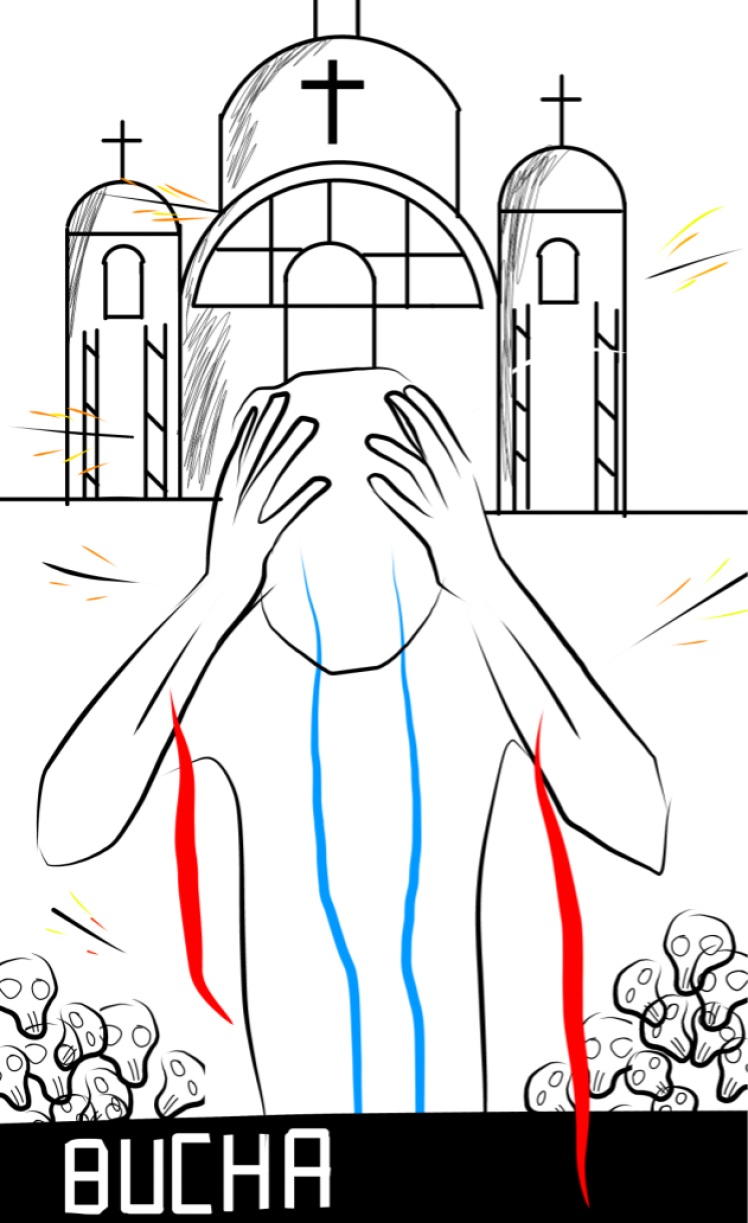

The Ukrainian army fully regained control of Bucha on April 2. Within a day, the bodies of the dead were taken away from the streets. Shortly afterwards, on April 5, the corpses were exhumed from mass graves dug up by Russian soldiers. One of the largest was near the church of Andrew the Apostle. The dead were retrieved from April 8 to 20 — it contained 117 bodies. A total of 416 bodies were exhumed and collected in the city. But this number may be greater.

The morgue and the hospital in Bucha were closed until April 11. Therefore, at first the bodies were taken to the morgues of the region — Bila Tserkva, Boyarka, Vyshhorod and the Kyiv Oblast morgue. The bodies found in Gostomel were transported to Obukhiv and Fastiv. In fact, all the morgues in the oblast were involved. There were about 250 bodies in them. More than 150 remained in Bucha — they had nowhere to go. On April 13, the morgue in Bucha began accepting and dissecting bodies, but even now not all bodies are brought here. 400 corpses in two weeks is too much for two forensic experts. In peacetime, about 20 dead people were brought here in a month.

I approach the information tent again and see my old acquaintance — Mykhailyna Skoryk. In 2014, when I had just left Luhansk, she was my first Kyiv editor.

— Spirin, where else would we see each other? Of course, in the morgue! — says Mykhailyna, — You used to collect corpses, and I was a journalist, and now you are a journalist, and I collect corpses.

Currently, Skoryk works in the staff of the Bucha City Council as an adviser to the mayor Anatoliy Fedoruk. Together with volunteers, she opened this information center near the morgue. Now they help identify bodies, work with the prosecutorʼs office, police and forensic doctors.

— We accept applications to the call center, compare data with lists of morgues, — says Mykhailyna, — We communicate with investigative teams, monitor photos from the Telegram channel, which are posted after the autopsy, and so identify dead and killed. Families and relatives do a lot of searching — they often find relatives using our guidelines. This is difficult, but in this situation, they are not ready to wait until the system works perfectly. Thatʼs why they do a lot on their own.

— And what exactly do relatives do? — I ask, — How do they look for the dead?

— We have a person from the administrative services center, a psychologist, volunteers who help to transfer bodies or just communicate with families. We collect data, ask forensic experts to perform an autopsy in the order in which relatives come, we say that the Bucha City Council helps to bury for free — in Bucha and Vorzel towns, Babyntsi, Blystavytsia, Myrotsky, Lubyanka, Gavrylivka, Sinyak, Zdvyzhivka, and other villages.

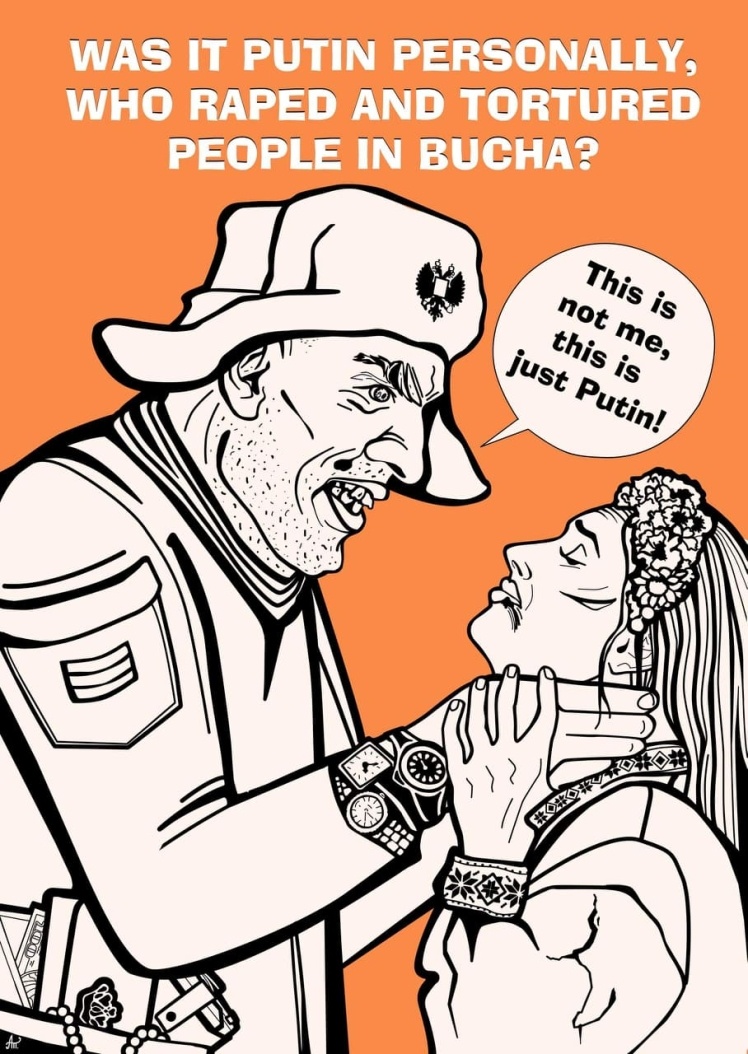

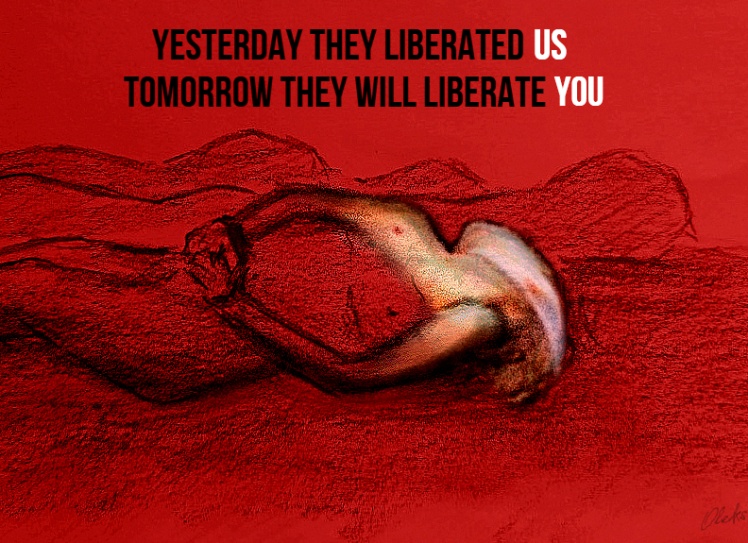

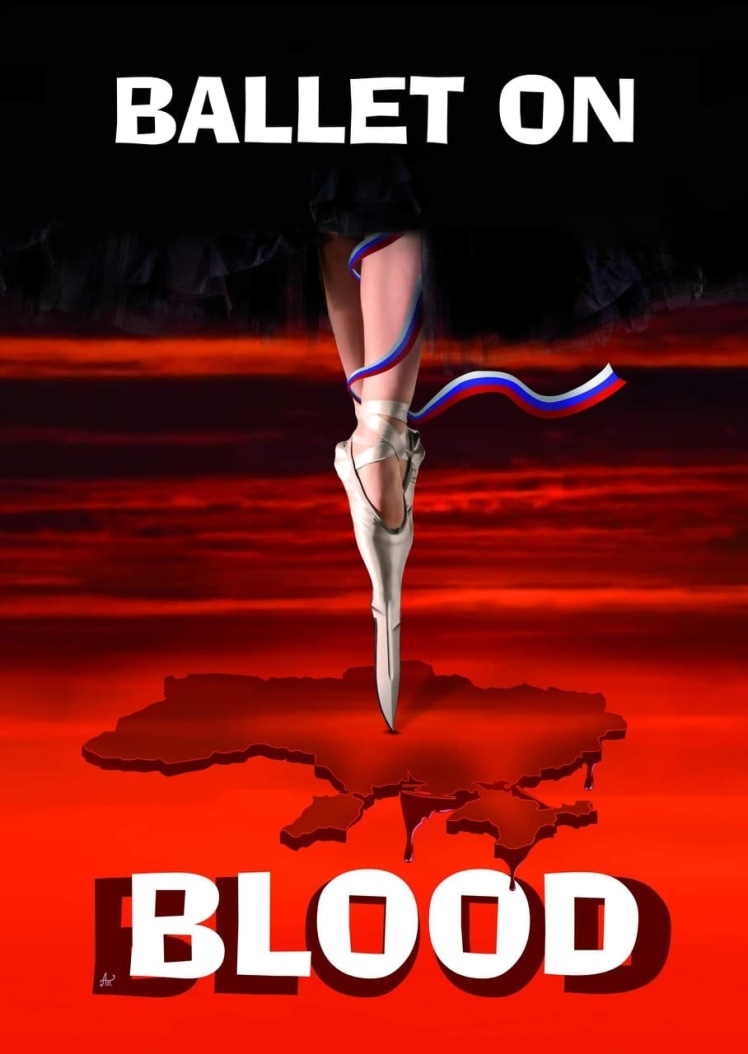

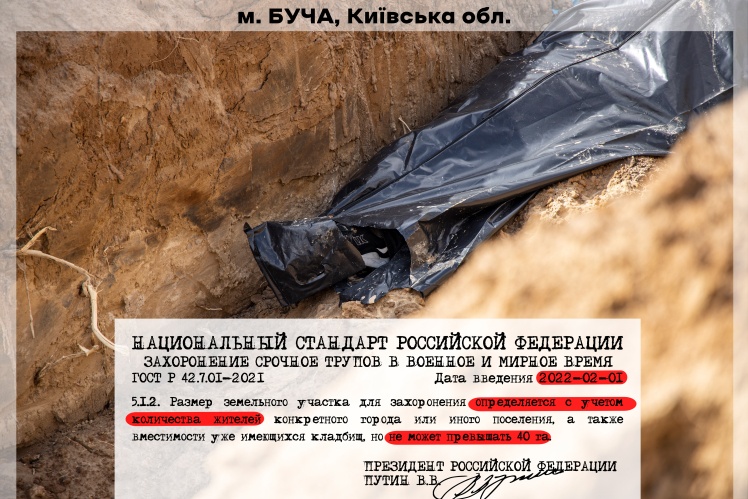

A few weeks before the invasion, Russia adopted a standard for mass burials. Russians went to Ukraine to kill civilians deliberately. We asked our readers to draw posters on this topic.

— And what do they do when they find the body? — I specify.

— Then the communal ritual service starts its work, — explains Mykhailyna, — It organizes the funeral. Sometimes there are 10-15 a day… In war conditions, everything is usually very modest, but it all depends on the wishes of relatives — we do not influence them. Just try to do what they ask. For example, there were requests to bury according to Muslim ritual.

As of April 30, 1,187 Ukrainians killed by Russian soldiers were counted in Kyiv Oblast. 1080 of them used to live in Bucha district. But the bodies are still being collected, for example, from Borodyanka and Makariv, where the morgues havenʼt worked. 200 people across the oblast are still missing.

In total, according to Deputy Interior Minister Mary Akopyan, more than 7,000 people have gone missing in Ukraine due to a Russian attack. About half of them were found.

Mykhailyna asks for help and to transfer the surnames that Alyona wrote down from two refrigerators to Google document. I go to the ambulance for a laptop, then sit on a chair in a tent and start copying. All this time, people are coming to the table and looking for their relatives in the lists. Today we managed to work with 17 corpses: six were transferred from a non-functioning refrigerator, another 11 were lying in working one, they were also described.

«Babel'»

Around 1 pm, Seva says that the work is finished and we can go to Kyiv.

4.

One week later, on May 3, DNA samples were collected at the Bucha morgue. This was done together with deputies of the City Council, the Office of the Prosecutor General and experts from France. It turned out that the French had a mobile DNA laboratory, and they agreed to come to Bucha to help collect biomaterials from people still searching for their relatives killed by Russian soldiers.

Currently, itʼs impossible to say, how many unidentified bodies were brought from the Bucha district, which includes 12 communities, more than half of which were under occupation. They are still being counted. DNA samples from them were taken by forensic doctors a little earlier. Now it is necessary to take samples of living people, and then compare both bases. If there are matches in the DNA of the living and the dead, someone will finally be able to bury their loved ones.

«Babel'»

At 10 am Iʼm going to the morgue together with volunteer Volodymyr Miroshnychenko, doctor Nadiia Davydenko and volunteer Babel photographer Katya Bandus. On Polyova Street, 19 there is already a crowd. These are sisters, brothers, mothers, fathers, children, grandparents, wives, husbands, grandchildren of murdered people. Some came from neighboring villages and towns. They lost contact with their relatives during the occupation of Bucha, and after the liberation they could not find them. Some know each other, exchange remarks.

— I saw your sister recently, — says the man in jeans and a light blouse to another man in a shirt and trousers. — And who are you looking for?

— For mother, — he answers. — As she disappeared on March 9, I still canʼt find her. The house was blown up, but there is no grave nearby, so they didnʼt bury her in the yard. Maybe she was in one of the mass graves. And who are you searching for?

— For grandma. She went out to gather firewood and disappeared.

«Babel'»

In addition to us, there are several other volunteers in the tent, coordinated by Mykhailyna Skoryk. She asks to bring two tables and six chairs from the hospital next door. We put tables and chairs near the tent: volunteers will use them to register people and issue numbers for the queue. Inside the tent office, there are packs of water for people, cookies, and napkins. Everyone gets their job. Someone will record the data, someone will take the relatives of the victims to a mobile laboratory, someone will monitor the queue and make sure that people are not aggressive, psychologists will calm them down, and another person will record the data of those who have already passed the samples.

«Babel'»

By 11 a.m., the French are setting up a large tent with a laboratory. 46 people are registered in the queue.

— Number one, — I shout, raising my hand. — Come up to me.

People have lined up in a line, a woman in her 70s takes a few steps forward. We walk along a large truck carrying decomposed bodies.

— What a sunny day today, — I say. — Who are you searching for?

— For my son. He called on March 6 and said that he would go looking for cigarettes, — she answers. — And he disappeared. They possibly took him to a checkpoint. And shot, — she says in a calm voice.

I take her palm in my hand, the woman sobs. We go to the tent, inside she is conducted by a volunteer Nadiia Davydenko, there are prosecutors from the Prosecutor Generalʼs Office, French criminal investigators, Ukrainian police. Nadia will help to fill in the documents. The biomaterial selection procedure is very confidential and involves bureaucracy and filling out a pile of forms. Prosecutors and forensic scientists ask the following questions to anyone who submits a sample:

— Who exactly are you looking for?

— Tell his (her) last name, first name, patronymic, date of birth, and address.

— Who was he (she) by profession?

— When did he (she) disappear or when did you last get in touch?

— Do you have his (her) documents?

— Is he (she) married? Any children?

— Are there other relatives who could also pass the DNA sample?

— Does he (she) have a passport?

— Are there any tattoos, scars or special signs on his (her) body?

— Did he or she go to the dentist? Were there any X-ray shots made? Is there a medical record? Are there any contacts with the dentist?

— Do you have a photo of a missed person?

Every time a person from the queue has to go through all the feelings of losing loved ones again and again. The information is translated into French. All this, as it turned out, takes a long time. It was originally planned that one person would hand over the samples in 5 minutes. But actually, it takes about half an hour.

«Babel'»

At 2 pm I call number 13. There are already 64 people on the list of those who have registered. It becomes clear: today we wonʼt be able to take the samples from everyone who came. I shout several times: “Number 13! Number 13!” Nobody comes. A few minutes later, one of the women in the queue quietly said: "We threw away the ticket number 13, it is unhappy. Next I am — number 14 ". The woman is about 40. She is looking for a mother. I take her to the lab and go back.

I meet another woman in her 50s near the refrigerator with corpses.

— Excuse me, are our relatives in this truck? — She asks. — It stinks so much.

— Yes, — I replied. — There are the remains of people there.

The womanʼs legs fail her, she faints. I manage to catch her under her back. The woman regains consciousness, I take her to the psychologistʼs tent.

— Forgive me, — she says, crying.

— Itʼs you forgive me, — I reply, trying to find a word.

In the laboratory, Nadiia Davydenko asks the prosecutor how many people we will be able to accept at this rate. The prosecutor clarifies this with the French criminalists. Both themselves and the translator look very tired. It turns out that you can put up another tent — then things will go faster. It takes about 20 minutes to deploy the second laboratory. People in the queue are also very tired, but are holding up well. They are happy to tell crowds of Western journalists about the atrocities of Russian soldiers in Bucha. Irpin, Gostomel and surrounding villages. The faces of the visitors are exhausted, it seems that some of them have aged in a few days, but some are still smiling.

«Babel'»

— What is your number? — I ask the woman in the knitted sweater.

— Oh, ttʼs 33, so my turn is not soon, — she says.

— Iʼm sorry, itʼs not fast there, — I say. — a lot of data and signs of the dead are asked to name. You will have to go through it again, we have a psychologist.

— Itʼs all right, — she answers easily.

Nadiia writes to me in Telegram that I can call number 15. I go to look for him or her, shout the number, it turns out to be a man who is looking for his daughter. While we go to the tent, he tells me the details.

— I think they found a woman who looks like my daughter, but without a head. Maybe a projectile [hit her], who knows. She was so young, born in 1985. I have a photo here, — says the man and takes out a bunch of color photographs. A girl on the seashore is on them.

I try to look into the distance with my glass eyes. Bring the man to the tent. A woman with an eight-year-old boy is already standing nearby. Volunteer Volodymyr Miroshnychenko explains that the childʼs turn is not coming soon. He is very hungry, and you canʼt eat before the test — so we need to let the boy go ahead. His DNA samples will be taken to find his father.

— My dad will come back from the war, — the boy says. — And he will teach me to ride a bike.

Miroshnychenko and I pretend that we donʼt exist. Most likely, his dad is here, next door — in the same refrigerator truck.

«Babel'»

5.

In the tent we called the office, there is a tablet on the table. Lists of bodies taken to the morgue have been uploaded to it: names, surnames and photos of bodies. Some are severely crippled. Volunteer Alyona periodically runs to the tent with photos brought by relatives of the victims. Vova Miroshnychenko, Nadiia Davydenko and Katya Bandus take turns taking pictures and looking for similar bodies on the tablet.

— Look, hereʼs a photo of my son, — says the man.

— Let me do the search, — Miroshnychenko answers. — The pictures [in the tablet] are not so nice.

— I donʼt really care — I served in Afghanistan, Iʼve seen it all, — the man replies.

Near one of the names there is a photo of torn legs and a caption: "Special detail: [had] military boots size 42, brand new."

At about 4 oʼclock in the afternoon, no more than 20 people remain. Volunteers in a tent led by Taras Vyazovchenko, a deputy of the Irpin City Council, decided to separate those who came for analysis. Those who came and do not live in Bucha, are taken first. Itʼs difficult to get to the town, and now there is gasoline shortage in the region. Those who are from Bucha were sent home. The French agreed to work another day so there will be time to take samples from everyone who needs this.

«Babel'»

Tired French journalists are sitting on the curb, they have accreditation from forensic doctors. Reporters are making a documentary about a man who was number ten. He found his fatherʼs car, it had only burnt bones.

— My father was with his mistress that day. But in the car are, probably, only his bones, — the man says. — The woman remained alive. But she does not want to tell why he went alone. In general, I have now handed over the samples and I hope that these are my fatherʼs bones. Will finally bury him.

People in the queue have already figured out for themselves who is following whom to take samples — depending on who lives farther from Bucha. Olena, a woman in her 60s, is sitting on a chair in a tent. Her son has disappeared.

«Babel'»

— The Russian soldiers took all men out of our house, — she says. — My son was a war veteran, he served in Donbas. Most likely, he was shot.

At this time I receive a message: in the village of Kalynivka, Kyiv Oblast, another grave was found, in which three people were killed with traces of torture, all with their hands tied.

Forensic scientists are asking for 20 minutes to have lunch: they havenʼt left the tents since morning. Two brothers looking for their mother sigh: they have to wait a bit longer.

— Iʼm sorry, itʼs been so long, because thereʼs a lot of data, — I reassure them.

— As soon as you enter the tent, youʼll understand why [it takes long], — says Nadiia.

— Yes, we all understand, — one of the brothers answers. — But what can we say about our mother? There are no scars, I do not remember any spots. Such a pity.

«Babel'»

Towards five oʼclock in the evening, it became clear that there were more volunteers than needed, and we can go home. I hug pensioner Olena and ask her to make a portrait of her.

— Well, you, Iʼm not dressed in a formal way today, — she jokes and smiles. — I keep thinking: if they wonʼt find any DNA matches — maybe my son is in captivity? So heʼs alive at least.

In a few weeks there probably will be all databases, results and lists. And then from all this a memorial complex needs to be made. This is the idea of Mykhailyna Skoryk. We wander to the car, in the parking lot riddled with car bullets. Taras brings a can of gasoline. Now this is a rare find. We refuel, shake hands. I sit in the front seat. There are clouds in the sky, explosions somewhere far away — sappers are demining the forest. Iʼm trying to write to my wife that Iʼm going home. My hands are shaking, the letters are confused, I drop the phone, pick up and record the voice. There is a bottle of vodka in the door of the car, I take a few big sips.

«Babel'»

— Letʼs go, — says Miroshnychenko.

The car starts and drives along high-rise buildings damaged by Russian shells, burnt shops, destroyed private houses, someoneʼs already rusty cars, gardens dug with funnels, mutilated fences. On the exit from the city there is a billboard. "The city of dreams. Live in Bucha“, it says.

Support Babel:🔸donate in hryvnia 🔸in cryptocurrency 🔸via PayPal: [email protected].

«Babel'»