How the Donetsk region was populated

The Donetsk region was sparsely populated for a long time due to the Mongol-Tatar invasion in the 13th century. Then these lands became a buffer zone between the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Muscovite Kingdom, and the Crimean Khanate. Already at the end of the 15th century, the period of Cossack colonization began. The lands of the modern Donetsk region were part of several palankas of Zaporizhzhia Cossacks, Don Cossacks also settled here. But after the Bulavin uprising at the beginning of the 18th century, the tsarist troops burned down almost all the settlements of the Don Cossacks, especially along the Siversky Donets River. Later, the Moscow state also evicted the Zaporizhzhia cossacks from these lands. The government of the Russian Empire began to invite nations from the Austro-Hungarian Empire to the Donetsk region — Serbs, Bulgarians, Moldovans, and Vlachs. They were allocated former сossack lands in the area of the Siversky Dinets River and its right tributaries — Bakhmutka and Luhan Rivers.

Painting by the Polish artist Józef Brandt "Fight of Cossacks with Tatars", 1890. Painting by the Polish artist Józef Brandt "The camp of the Zaporizhzhia Cossacks at the end of the 16th — the beginning of the 17th century", 1880.

Wikimedia

The colonists were lured with lands that were given to them for life, with money, help for accommodation, benefits for industries and trade. Instead, the emigrants were to form infantry and cavalry regiments under the command of Serbian officers Jovan Šević and Rajk Preradović to guard the southern borders of the Russian state. The new administrative-territorial military unit with its center in the city of Bakhmut was named Slavic Serbia.

But this attempt at foreign colonization essentially failed. Slavic Serbia existed for only 11 years — from 1753 to 1764. There were very few emigrants — only a few thousand, including women and children. They quickly assimilated with the local population. Now, their presence is only reminded of by toponyms. For example, the name of the village of Depreradivka is from the surname of one of the Serbian colonels-settlers, Rajk Preradovych.

Another attempt at foreign colonization of the Donetsk region was more successful. In the second half of the 18th century, the Russian Empire occupied the Crimea. Greeks, Bulgarians, Armenians, and other Christian peoples began to move from the peninsula to the northern Azov region. As of the summer of 1778, more than 30,000 people were resettled from the Crimea, more than half of them Greeks.

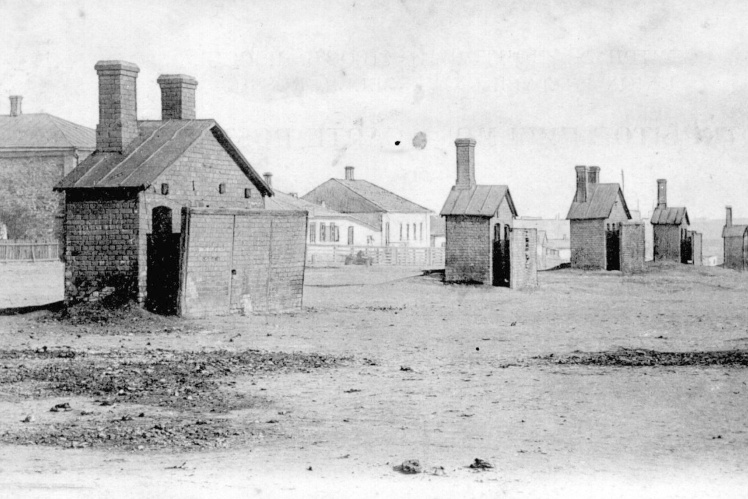

General appearance of Bakhmut in the 19th century.

Wikimedia / «Бабель»

Greek settlers were allocated land on the coast of the Sea of Azov and the right bank of the Kalmius River. They were exempted from military service and taxes for ten years, were allowed to create their own self-government bodies, and the Greek metropolitan retained independence of church administration. Greeks founded more than 20 settlements on the lands of modern Donetsk region. Settlers named them after the Crimean villages where they came from. Thus, the villages of Bakhchysarai, Yalta, Urzuf, Sartana, Karan, and Mangush appeared in the Donetsk region. The city of Mariupol became their center.

Coal deposits were discovered in the Donetsk region in the 18th century. The gradual industrialization of the region began. European colonists-industrialists played a significant role in this. German settlements on the territory of the modern Donetsk region appeared at the end of the 18th century. Among the most famous is the New York urban-type settlement near Toretsk, founded by German Mennonites. The colonists built mills and factories here — brick and agricultural machinery manufacturing.

The French joined the Germans — in the modern city of Druzhkivka, which isnʼt far from Kramatorsk, they founded an iron and steel mill. Successes attracted Belgian industrialists to Druzhkivka. The Belgians built the Toretsk steel and mechanical plant, which produced equipment for the railway. And modern Donetsk city itself arose on the site of a workersʼ village founded by the British industrialist John Hughes. He built a metallurgical plant here with a full cycle of production: from coal to coke to metal. At the beginning of the 20th century, Hughesʼ enterprise became a leader in steel smelting in the then Russian Empire. And the workersʼ village was turning into a European town, where engineers and craftsmen from Germany, England, France, and Belgium came to work.

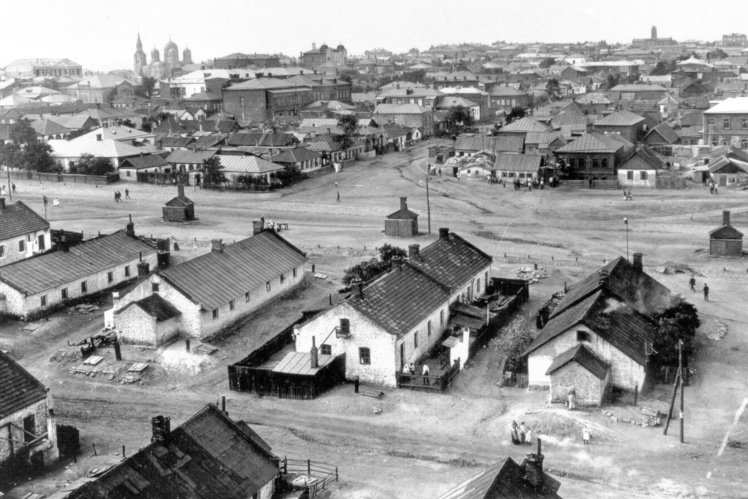

Yuzivka at the beginning of the 20th century

Wikimedia

With the establishment of Soviet power, the Bolsheviks took away enterprises from Europeans and staged mass repressions, the most terrible of which was the Holodomor of 1932—1933. After the beginning of the Second World War, the German colonists of the Donetsk region were deported en masse to remote regions of the Urals, Siberia and Kazakhstan. And the Soviet authorities forcibly resettled residents of various regions of Ukraine, especially the western ones, to the Donetsk region. During one of the waves of deportations in 1951, approximately 30,000 Boykos and Lemkos were transported to the Bakhmut district of the Donetsk region. They were resettled to three villages: Zvanivka, Rozdolivka, and Verkhnyokamyanske. Here they still live as a compact community, preserving their own traditions and customs.

Members of the society for joint cultivation of the land transport the pantry of the dispossessed peasant P. Yemets to the general pantry, Hryshyne district of the Donetsk region, 1930s of the 20th century. Dismantling of peasants, Udachne village, the Donetsk region, 1930s. Children collect frozen potatoes on a collective farm field, Udachne village, the Donetsk region, 1933.

Музей голодомору / «Бабель»

How Russia is destroying the culture of the Donetsk Greeks

Almost all Greek settlements in the Donetsk region were occupied by the Russians in the first months of the full-scale war and completely destroyed. These are Mariupol, Sartana, Volnovakha, the villages of Granitne, Bugas, Chermalyk, Starognativka, Staromlynivka. Libraries, private archives, and museum collections are buried under their ruins. Some of the materials were lost forever during fires and bombings, and what survived was stolen by the Russian military, as happened in Mariupol. In April, the local history museum of Mariupol burned down during artillery shelling along with a large Greek exposition, among which were the works of the founder of local Greek literature, Georgy Kostoprav. The Russians bombed and looted the art museum named after Arkhip Kuindzhi, a Ukrainian artist of Greek origin. The Museum of Greek History and Ethnography in the village of Sartana was shelled by the Russians in the first days of the invasion. What happened to its collection is unknown.

Arkhip Kuindzhi Museum in the 20th century. This building survived the First and Second World Wars, but was destroyed in March 2022 by the Russian invaders.

Wikimedia

“When we say that the Russian war against Ukraine took away the homes of the Nadazov Greeks, we are not explaining anything,” Oleksandr Rybalko tells Babel. He studies the Urum and Rumey languages spoken by the Azov Greeks. “The Russian occupation, their bombing, put into question whether this national community will exist, because their languages and culture are being destroyed.”

Even before the resettlement from the Crimea in the 18th century, the Greeks were divided into two ethnic groups — the Rumei and the Urum. The Rumeys speak a dialect close to Modern Greek, and the Urums speak Turkic. Rybalko explains that these languages are unique, because they existed only in the Donetsk region for 250 years. But in the last hundred years, they gradually disappeared. Initially, because of the Bolsheviks, who in the 1930s carried out ethnic cleansing of the Greeks. More than six thousand people were shot in the Donetsk region alone, they were accused of espionage and counter-revolutionary activities. When Ukraine gained independence, the Greeks themselves, instead of learning their native languages, switched to Modern Greek in order to communicate with Greeks around the world. And after February 24, 2022, almost all Greeks left the occupied territory.

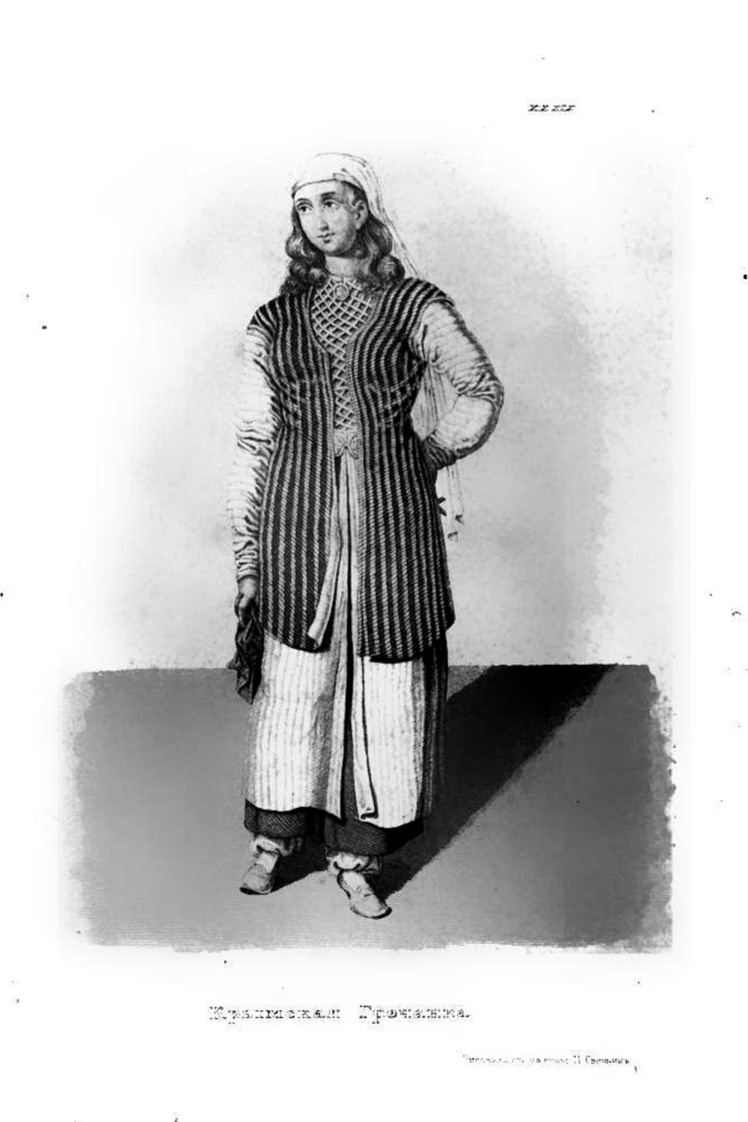

Traditional dress of the Crimean Greeks in the 18th century.

Wikimedia

“Among those who left the occupied territories, there are almost no native speakers — they remained in the occupation, mostly because of their age. There is no connection with them. Not everyone has the Internet,” says Rybalko. “In recent years, we have produced alphabets in the languages of the Nadazov Greeks, calendars, books, CDs with songs. If we didnʼt do it then, we wouldnʼt be able to do it now — the people who helped make them are now under occupation.”

Despite this, Rybalko still remains an optimist. He says that now many Greeks who were evacuated abroad felt that they were missing their roots — their native language.

“These languages are not such that you can use them to conduct a dialogue on complex topics, because they did not develop for many decades, they were banned. They can be used to talk about everyday topics,” says Rybalko. “I notice how people are now looking for their native, their home in these languages, and therefore I think that we will preserve them.”

Translated from Ukrainian by Anton Semyzhenko and Dmytro Raievskyi.

Letʼs preserve Ukrainian history together with Babel. Support us: 🔸 in hryvnia 🔸 in cryptocurrency 🔸 via Patreon 🔸 or PayPal: [email protected].