The tribunal for Yugoslavia was established in May 1993, when the wars in its member states were still going on. Did this affect the actions of those who later appeared before the tribunal?

Yes, I think so. This was well demonstrated by the Srebrenica massacre hearings, which took place in 1995, after the Tribunal was launched. Eight thousand Bosnian Muslims, men and boys, were killed there. During the hearings, it became clear that they were buried in mass graves. And in a few months during a large-scale operation, they tried to hide the body better. The killers were afraid that others would find out about the crime, and there will probably be investigations and trials. So they returned to the mass graves, took out the remains and reburied them elsewhere. Sometimes they did this several times to make it harder to find the victims and bring the perpetrators to justice. So far, not all the bodies of those killed in Srebrenica have been identified. So the killers were afraid of the tribunal. But instead of committing crimes, they decided to just hide them.

Stephanie van den Berg

What evidence did the tribunal judges take into account? For example, if we talk about genocide.

There were two major cases, but only one court recognized the genocide — the case of Srebrenica. There was no direct evidence in that case. The best evidence would be a recording where someone said: "Kill them all." But no one said this on record and it was impossible to verify who gave such an order. It was thought that it was General [Radislav] Kristic, but it could not be legally proven, so in the end the evidence was not accepted. But the judges could see it from the action. For example, such evidence was the huge number of people who were killed. Virtually none of the men who were in Srebrenica at the time survived. It seemed that the enemy tried to just wipe people out of the territory, which is genocide.

The defense argued that the women and children survived, so it was not genocide. However, the court noted that killing all men makes community life impossible. And the fact that women and children were expelled from the territory to live elsewhere is also, in fact, genocide. So this area was ethnically cleansed.

Mass graves, murders, testimonies of soldiers who were in punitive units and surrendered and confessed, were strong evidence. In addition, it is known about the decisions on clearing areas [of people of specific ethnicity]. The general scheme of actions confirmed that it was genocide.

There was another case in which the prosecution believed that Bosnian Serbs were trying to commit genocide. This is a case of concentration camps in central Bosnia — in Prijedor — at the beginning of the war. The argument was that people were in conditions aimed at eliminating them, which can also be seen as genocide. But the judges explained that it could only be confirmed if a large number of people had died in the camps. Therefore, the court acknowledged that crimes against humanity were committed there, but not genocide.

Two young Muslim women weep over one of 613 coffins of victims of the 1995 Srebrenica massacre in a hall at the Potocari cemetery and memorial near Srebrenica on July 10, 2011 in Potocari, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The newly-identified remains of the 613 victims were scheuled to be buried in a ceremony to be held on July 11, the 16th anniversary of the massacre.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

The tribunal for Yugoslavia lasted 25 years. Why did it take so much time? Will Ukraine also have to wait that long?

International law is rather slow. Only a preliminary hearing can last 4-5 years. The tribunal for Yugoslavia was the first one since Nuremberg tribunal. Nobody knew how to conduct it. It was necessary to determine everything: how to collect evidence, what are the rules of this court, how to choose judges, what kind of law to use. Finally the tribunal organizers came to a mixed system. It took several years to set it up, and only then could the investigation be launched.

At first, the Yugoslavia tribunal could not detain people. Bosnia was divided, no one wanted to arrest people from their side. The first one detained was a man who fled as a refugee to Germany, where he was identified as a security guard from the concentration camp. The tribunal provides for cases of those most responsible for the crimes, and although the camp guard is not that person, he was the one whom the tribunal managed to get.

Evidence was collected for a long time. It is very difficult to investigate crimes in a war-torn country. The International Criminal Court is now doing this in Ukraine, but it has not done so before.

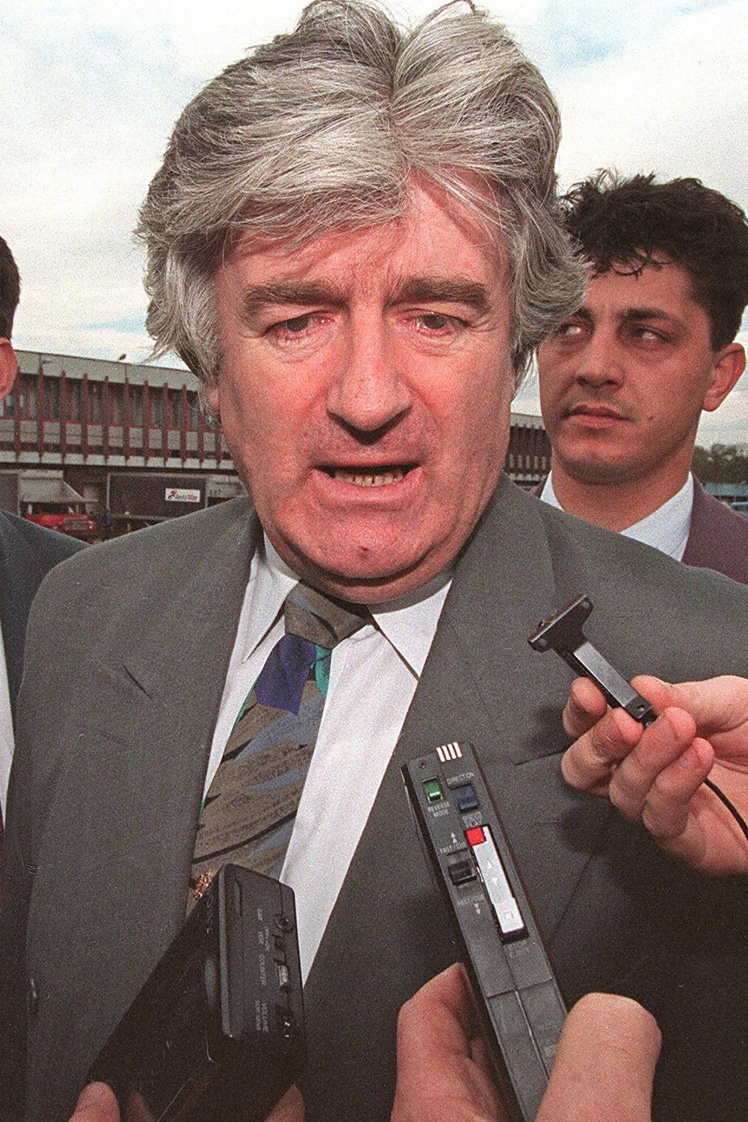

The hearing of the first case also takes a very long time, as many important provisions on the legitimacy of the tribunal and the possibility of considering it need to be substantiated. When that happened, UN forces stationed in the countries of the former Yugoslavia were able to detain the suspects at the tribunalʼs request and take them to the Hague. But even then it was impossible to deliver the key people who bore the greatest responsibility. Because if a political leader is arrested, it will lead to unrest, and the UN countries have tried to maintain balance and peace. At that time, the Balkan countries wanted to become candidates for membership in the European Union. One of the pillars of the EU is the rule of law. And for the countries of the former Yugoslavia to meet these requirements, they had to work with the tribunal to do everything possible to transfer the suspects to the Hague. It was this pressure that made it possible for [Radovan] Karadzic and [Ratko] Mladic to be handed over to the tribunal.

Did journalists and lawyers believe at the beginning of the proceedings that Serbian President Milosevic would be brought to justice?

While he was in power in Serbia, we did not believe that it was possible, no one could get close to him. Although the tribunal issued an arrest warrant when Milosevic was still in power. After mass protests and elections, the regime changed and he was removed from power. The new government was ready to get rid of Milosevic and gladly sent him to the Hague. If you draw an analogy with Putin and ask if it is possible for him to get to the Hague, I would never say "never". Especially if the regime changes in Russia and there will be a warrant for his arrest. I really did not believe that Milosevic would be in the Hague. And I was sure that Karadzic and Mladic would die while trying to flee, I didnʼt think they would be sent to the tribunal. In the case of Milosevic, this was clearly a political move. And a few years later, the prime minister who betrayed Milosevic killed one of the latterʼs supporters.

Former Yugoslavia President Slobodan Milosevic arrives for the start of his defense case at the Yugoslavia war crimes tribunal in the Hague, the Netherlands, 05 July, 2004.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Milosevic died in the cell and did not hear the verdict. To determine whether he was killed, an investigation was conducted, and it showed that no, he was not. But then the prosecutors studied the treatment Milosevic was receiving. Are there any results?

Milosevic was not in very good health, like most men in their 60s. He had high blood pressure and refused the treatment offered to him in the Netherlands: he wanted to be sent to Russia, and asked for it. During the investigation, it became known that he was taking unlicensed medicines, which were not prescribed to him by local doctors. One of the drugs, in particular, is a cure for Hansenʼs disease [this disease is also called leprosy], which he did not have.

How did the accused behave in court?

Most denied the charges, but some criminals pleaded guilty. Two high-ranking officers in the Srebrenica murder case did so and then testified against others, and the prosecutor asked for a milder punishment for them. Former President of Bosnia and Herzegovina Biljana Plavsic also pleaded guilty, but later pleaded not guilty [she also called for Karadzic and Mladic to surrender].

Those who denied the allegations always had a mixture of arguments: "I wasnʼt there when it happened", or "I didnʼt know about it", or "I was just there, doing my usual job, and I donʼt know what my plans were". And the commanders said that their task was strategy, so they did not know what their subordinates were doing on the ground.

At the level of Milosevic, there were arguments such as "I was for peace, and this is what I did for peace: here are these negotiations, here are others, and here is a peace agreement". Another argument: they dealt with issues at a high level, so they could not know all the details on the ground. In such cases, the evidence could be the testimony of a diplomat who would say: "I saw you one day and in conversation raised the issue of concentration camps or killings in Srebrenica". But if high-ranking officials knew about it, they could stop the crimes at that moment. If they found out too late, the perpetrators should be punished. And if they didnʼt do that, it is also their responsibility. Proof of the involvement of commanders can also be considered cases when they, knowing about the accusations of mass murder or other crimes, gave medals or other awards. In such cases, it is not necessary to prove that the commander knew: itʼs enough that he could know.

Ratko Mladić, a Bosnian Serb convicted war criminal. Biljana Plavšić who served as President of Republika Srpska and was later convicted of crimes against humanity for her role in the Bosnian War. Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic flanked by bodyguards arriving for a private visit at Moscow airport.

Getty Images / «Babel'»; Wikimedia

Letʼs draw parallels with Ukraine. Specific military personnel from specific Russian units raped Ukrainian women, children and men. This is public information. If their commanders do not investigate these cases and bring the guilty military to justice, can they also be brought to justice?

Yes. This is a classic team responsibility.

Not everyone who found himself on the dock at the tribunal received their sentences. Were they really innocent or was it big politics?

Those who could prove that they were not at the scene of the crime or did not have the authority to influence the events were found not guilty by the judges. The same happened when the accused argued that they were aiming at the police station and hit a nearby house. The police station is not a civilian target, so hitting it is not considered a war crime. During the tribunalʼs operation, it was considered that a 5-kilometer error was not a war crime. For example, this is how the Croatian generals were justified. This approach was strongly criticized even then. I donʼt think that an error of 5 km is acceptable now.

Were there war crimes suspects who never appeared in court?

Yes, many. There are still thousands of cases in Bosnia in which people are accused of war crimes. They are being investigated by local prosecutors, but they are unable to cover everything. Because the tribunal focused on global war crimes and the senior officials responsible for it. And the rest should be tried on the spot. That is why thousands of people in Bosnia are still facing charges that have yet to be confirmed in court or have not even seen their accusations. And a lot of people are forced to go to the same cafes where security guards from the camps go now.

Where are the criminals who received their sentences in the tribunal?

The suspects are in prison in the Hague while the trials continue. The Netherlands became the masters for the tribunal, but they did not want all the criminals to stay with them later. Therefore, other countries must take them away to serve their sentences. Agreements have been signed with Norway, France, Sweden, Germany, Belgium, Poland and other countries. The offender can serve his sentence in any of these countries, except his own.

There are UN standards for detaining criminals, sometimes they are quite high. I know that Biljana Plavsic was serving her sentence in a super-luxurious prison where she had cooking classes, and this greatly irritated people in Bosnia. Karadzic served in the UK, Kristic in Poland. Many people in Sweden.

Bombed houses in a city that was half-Muslim and half-Croatian.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

What struck you most when you watched the tribunal for Yugoslavia?

When you write about the tribunal and the terrible things that happened during the conflict, you always think about how terrible the country and the people should be to allow these atrocities. If you look at everything through the prism of the tribunal, it seems that these are primitive people who are stuck in the Middle Ages and full of hatred for each other. So I went on vacation to Bosnia, Croatia and Serbia to see everything with my own eyes. And I saw that these are beautiful countries with wonderful, hospitable people and delicious food. When I visited them, I realized that war can happen to ordinary people, itʼs not that far away. Before the war, these people had a normal life, did what we all do, and then, through political games, found themselves in a terrible conflict, when the neighbors went against each other.

What can Ukraine learn from the tribunal?

The idea was that if there were sentences, people would recognize them, reconcile and be able to live together again. I think itʼs too much to demand. Tribunals are needed for people to understand that there is some form of justice. But we must remember that this process has been going on for many years. Victims need to understand that it can be emotionally difficult because they have to testify, and when the perpetrator is punished, it still wonʼt change the situation, and itʼs a harsh reality.

The tribunal is also a very dry process. People think that they will come to court, there they will be able to tell their own story, like in American films, and this will be the moment when they will be freed from their suffering. But this is not the case. The tribunal was not designed for victims, but for criminals. The victim is required to provide very limited dry information, and this often irritates people.

We need to tell people what can happen to them during the hearings. Including that it will last a long time, and in the end their house will still be destroyed, and the family they lost will not come back, and everything will be as difficult as before the offender received the sentence. They may feel a little better, but that wonʼt change the reality.

It is very important that Ukraine spends so much effort to gather evidence and then seek punishment for war criminals. And even if they serve their sentences in a Norwegian or other super-comfortable prison, itʼs still a prison where you canʼt walk freely, play with your grandchildren, where you have to be checked before you take a shower, and ask permission to go outside.

A memorial to the killed Muslims in Srebrenica.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Translated from Ukrainian by Anton Semyzhenko.

Milosevic waited for the verdict for 5 years and it didnʼt came. We will definitely wait for Putin to get to jail, but it will be easier if you support us: donate in hryvnia 🔸 in cryptocurrency 🔸 Patreon 🔸 PayPal: [email protected]