What kind of cases this refers to?

In the late 1980s, the united Yugoslavia was bursting at the seams. In one of its republics — Bosnia and Herzegovina — Bosniaks, Bosnian Croats, and Bosnian Serbs lived at that time. In November 1990, the first multi-party parliamentary elections were held in the country. Three new parties joined them: the Croatian Democratic Union, the Serbian Democratic Party and the Party of Democratic Action, which represented the interests of Muslim Bosniaks. The powerful Union of Communists of Bosnia and Herzegovina also took part in the elections, the fight against which actually united three opponents. And they won. But each of the parties had their own interests, their conflict was a matter of time.

In the summer of 1991, Croatia and Slovenia declared independence from Yugoslavia. Bosnia did the same on October 15th. And the society split completely — Bosniaks and Croats wanted independence, and Serbs were mostly against it. The Serbian Democratic Party began to create alternative government bodies in various municipalities, a separatist government of the Republika Srpska was formed on the territory of Bosnia. The remnants of the Yugoslav army and Serbia supported the separatists. In March 1992, the war actually began.

In the Republika Srpska, persecution of Bosniaks and Croats began, which quickly turned into mass murders, in which both the military, the civil administration, and unofficial paramilitary groups participated. The International Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) had four key cases — the head of the Prijedor municipality Mylomir Stakic, the head of the parliament of the republic Momcilo Kraišnik, the policeman in the concentration camp Goran Jelisic and general Radislaw Krstic. Genocide was recognized only in one case — in relation to Krstic. Other cases include crimes against humanity and war crimes.

The case of Milomir Stakić

In 1992, the Serbian Democratic Party seized power in the municipality of Prijedor in order to establish its own authorities there. The municipal assembly was headed by doctor Milomir Stakić. Attacks on non-Serb civilians began. Paramilitary groups of Serbs destroyed their houses, intimidated them, forced them to flee or sent them to concentration camps in Omarska, Keraterm and Trnopolje. For example, the Serbs detained the evacuation column of Bosniaks from the town of Kozarac, separated men and women and sent them to different concentration camps.

The Serbian military abused the prisoners of the camps, sometimes beating them to death. There were also cases of mass executions. At the end of July 1992, more than 120 people were killed in the Omarska camp — they were taken out of the camp by buses and executed.

In addition, the municipal authorities limited the rights of Bosniaks and Croats. There was a curfew for them, they were deprived of their positions, they were not provided with medical care, and their children were not allowed to go to school. Stakić publicly said that Muslims in Bosnia were "artificially created" and insisted that all "enemy" Muslims must be "removed" from Prijedor and the surrounding area.

In total, Stakić is responsible for the death of approximately 3,000 people in the municipality of Prijedor. Prosecutors insisted that the crimes could be interpreted, in particular, as genocide against Bosniaks and Croats.

A Bosnian woman cleans a freshly dug grave at the memorial cemetery in the village of Potocari near Srebrenica, July 8, 2010.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Arguments of the court, why the case of Stakić is not genocide

- Genocide is the deliberate physical destruction of an ethnic, religious or racial group or part of it. Therefore, the key thing that the tribunal paid attention to was the proven intent to destroy the group or its part. That is, the intention must be not just to kill people immediately, but to destroy an entire ethnic, religious or racial group.

- The court disagreed with the prosecutionʼs contention that there was a common group of "non-Serbs" that included Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats. Thus, the prosecutors had to prove the intention to destroy each group separately.

- Deportations are a separate crime that is not genocide as such. The court decided that the dispersal of a group or its breakup is not sufficient to speak of genocide.

- The number of victims is not an indicator too. In order to recognize a purge as genocide, it must be the killing of all members of a group within a small area. But the killing of Bosniaks, for example, in different places on a large territory is not genocide, because it doesnʼt indicate the intention to destroy Bosniaks as such.

- Stakićʼs goal, according to the court, was to separate Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats from the Serbian community, not to destroy them. Killings and abuses were intended to instill fear and force the population to leave, and property was destroyed so that Bosniaks would have nowhere to return. But there was no intention of genocide. "If the goal was to kill all Muslims, appropriate structures would have been created for this purpose," the tribunal noted.

- In Stakićʼs public speeches and private conversations, there were no words about the complete elimination of Bosniaks or Bosnian Croats. Stakić said that Muslims in Bosnia were "created artificially". But this is not genocidal intent, because it was about territory, not total destruction.

Sentence

Milomir Stakić was initially sentenced to life imprisonment, but the appeal reduced it to 40 years. He was found guilty of crimes against humanity and war crimes. Now he is in prison in France.

The case of Momčilo Krajišnik

Krajšnik was the chairman of the Assembly of Bosnian Serbs, the parliament of the separatist Respublika Srpska. Prosecutors considered him an accomplice to the genocide.

For example, in the spring of 1992, the Serbs captured Sanski Most and began to expel Bosniaks from the city and its surroundings. There was a case when eight Serbs in camouflage came to a farm where 30 women and children remained. The only local man tried to act as a negotiator, but he was shot dead. And when the frightened women and children started to run away, the Serbs started shooting at them. In total, 16 people were killed then.

In a nearby village, 19 Muslims were led to the Vrkhpolje bridge, four were killed on the way, and the rest were brought to the bridge. They took their belongings and documents and forced them to jump off it. When they were in the water, they were shot.

On June 27, 1992, the Serbian military arrived in the Muslim village of Kenjari. They captured 20 Muslim men and took them to the leader of the Serbian Democratic Party in Sanski Most, Vlado Veres, who assured them that there was nothing to fear. After that, Serbian soldiers led the Muslims to a house in the village of Blaževići, locked them there, threw grenades at the house, and then opened fire on those who tried to escape. After that, the house was set on fire. 18 people died, two managed to escape.

In Vyšehrad, the detainees were locked in a house and burned alive — 66 Bosniaks died there. A total of 148 people, including children and women, were executed in Ključ. In the area of the city of Zvornik, on different days of May 1992, Serbian military and paramilitary groups executed almost 440 Muslim men.

The investigation had evidence that Momčilo Krajišnik was involved in these crimes.

Momčilo Krajišnik, a close associate of former Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadžić, makes his first public appearance at the UN war crimes tribunal in The Hague on April 7, 2000.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Arguments of the court, why Krajišnikʼs case is not genocide

The courtʼs position was based on almost the same arguments as in the Stakić case. According to the court, Krajšnikʼs goal was to expel Bosniaks from the territory of the Republika Srpska, not to destroy them. Krajšnik claimed that Bosniaks are not part of the Muslim world and nation, therefore they should be deprived of their territory. But he did not say anything about complete extermination.

Sentence

Momčilo Krajišnik was sentenced to 27 years for crimes against humanity. In 2009, an appeal reduced the prison term to 20 years. He served two-thirds of the term and was released in September 2013. Died of covid in 2020.

The case of "Serbian Adolf" Goran Jelisić

Jelisić was born in the town of Bijelina, where Serbs, Bosniaks, and Croats lived — according to neighbors, he had friends among them all. Before the war, he worked on a farm, then went to prison for fraud with checks. In 1992, when the Republika Srpska came into being, the new government offered the 24-year-old Jelisić freedom if he joined the police. He agreed and became a senior guard at the Luka camp in the Bosnian town of Brcko, where hundreds of Bosniaks and Croats were held.

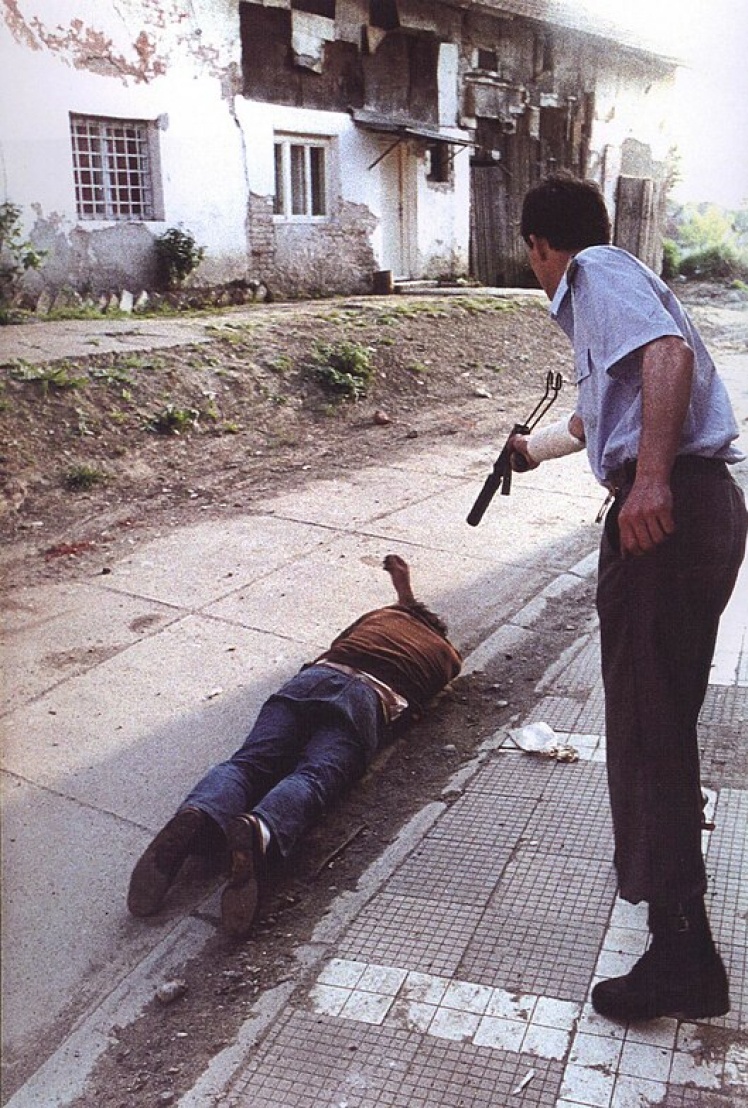

Jelisić shoots a man in Brčko. Bosnian Serb war criminal Goran Jelisic walks into the courtroom of the International Criminal Tribunal on February 22, 2001.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Jelisić called himself "Serbian Adolf", publicly said that he came to Brčko to kill Muslims. He told the detained Muslims in the Luka camp that their lives were in his hands and that 70% of them would be killed and the remaining 30% would be severely beaten. Jelisić said that he hated Muslims and that they should all be killed, and those who survived could be slaves to clean toilets. He wanted to sterilize women.

He regularly executed prisoners in the camp. One of the witnesses said that Jelisić had to execute 20 to 30 people before drinking his morning coffee. Sometimes he forced the prisoners to play "Russian roulette" with only one bullet in the barrel of the revolver.

Prosecutors were convinced that Jelisićʼs actions were genocide, because he systematically killed Muslim Bosniaks and did not hide his desire to kill them precisely because of their identity.

Why Jelisićʼs case is not genocide

In Jelisićʼs case, the court also did not see an intention to physically destroy the group as such, in whole or in part. "The defendantʼs conduct appears to indicate that although he clearly singled out Muslims, he killed arbitrarily and not with the express intent to destroy the group," the court noted.

Jelisić was helped by the norms of criminal law, according to which the court interprets any doubt in favor of the defendant, so Jelisić was found innocent of the crime of genocide.

Bones of victims of the massacre in Srebrenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina, July 10, 2018. Ramiz Nukić, who survived the Srebrenica massacre in 1995, holds the bone of one of the victims of the massacre, on July 10, 2018.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Sentence

Goran Jelisić was found guilty of crimes against humanity and sentenced to 40 years in prison. He is serving his sentence in Italy.

The case of Radislav Krstić

General Radislav Krstić was an officer in the Yugoslav Peopleʼs Army before the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and when it began, he joined the Army of the Republika Srpska. From July 1995, he was the commander of the Drina Corps, which fought near the Muslim enclaves of Srebrenica and Žepa. Since 1993, these enclaves have been official security zones under the protection of UN forces. The peacekeepers had a base in the village of Potočari, which is not far from Srebrenica. Bosniaks from surrounding settlements fled to Srebrenica.

In March 1995, Radovan Karadžić ordered the two enclaves to be separated and access to humanitarian convoys closed. The operation was planned by Krstić, it began on July 5, and in four days the Serbs surrounded Srebrenica and received an order to capture it.

Bosniaks began to flee from Srebrenica to the base of peacekeepers — by the evening of July 11, there were already 20,000 to 25,000 of them there. A few thousand were able to get to the territory of the base, the rest remained in the fields and in hangars nearby. There was no food or water for the refugees at the base, the UN forces invited negotiations with the chief of staff of the Respublika Srpska army, Ratko Mladić, about the safe evacuation of the Bosniaks. On July 11-12, three rounds of negotiations were held.

Krstić was present at all negotiations. Mladić agreed to the evacuation, but on the condition that all men between the ages of 16 and 70 would be checked for war crimes.

At that time, the first murders of Muslims were already taking place in the Potočari area, outside the base, and several women were raped. Bosniaks hastily boarded buses. UN peacekeepers tried to escort the buses, but the Serbs took their vehicles.

On the left are the victims of the shelling in the morgue on December 1, 1994 in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. On the right, General Radislav Krstić speaks before the International Tribunal in The Hague.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

On the way, the Serbs removed men from the buses, both those younger than 16 and those older than 70. The detainees were gathered behind the zinc factory. All were ordered to hand over their belongings, including personal documents and wallets. It was all burned later. Some of the men were executed just outside the factory building, which was called the "white house". But most were put on trucks and taken to the neighboring settlement of Bratunac, on the border with Serbia.

There, Bosniaks were sent to empty schools and warehouses, where they were kept for several hours. And then they were taken in small groups to the places of execution — usually these were fields. Those who survived were shot repeatedly, sometimes specifically waiting for several hours for people to suffer. After that, the bodies were either collected and taken to dug trenches, or an excavator covered them with earth on the spot.

Another thousand to fifteen thousand Bosniaks were gathered in a warehouse in Kravica, which Serbian soldiers pelted with grenades. The building was surrounded and those who tried to escape through the windows were shot.

In September 1995, the Serbs dug up some of the graves, and the bodies were taken to other graves and buried again. At the time of the court hearings, only 2,028 bodies were found, more than 7,000 Srebrenica Bosniaks were considered missing. It is now known that the Serbs executed more than 8,000 men.

Bosnian soldiers unload the body of an elderly man who died during the evacuation from Srebrenica, March 29, 1993.

Getty Images / «Babel'»

Arguments of the court, why the Krstić case is genocide

- The Serbs publicly stated that they had to check men of "conscription age". But their documents were burned, and there were no checks. In addition, among those killed were people with disabilities or diseases, minors and old people who did not pose any military threat to the Serbs. That is why the Serbs lied about their intentions — they were going to kill everyone from the beginning.

- The Serbs returned to the places of execution and finished off those who were still alive.

- The court called the fact that people were buried in common graves, some of which were later dug up, and the remains were reburied in areas far from Srebrenica, as a convincing sign of the intention to destroy the group. This made it impossible to bury the victims according to religious and ethnic customs, and difficult to identify.

- The loss of three generations of men had a catastrophic effect on the Bosniak community of Srebrenica, which could no longer resume its normal life.

- In addition to local residents, Bosnians who came to seek protection from UN peacekeepers were also killed in Srebrenica. Therefore, the subsequent events were an attack specifically on a part of the group of Bosniaks.

- Srebrenica was a Muslim enclave surrounded by Serbian settlements. It was in the interests of the Bosnian Serbs to destroy the Muslim community in order to unite these settlements.

- Regarding Krstić personally, the court did not prove that he gave orders or was present at the executions. But Krstić must have known about the plan to exterminate the men, as he was present at the negotiations. And he visited the "white house" at a time when executions had already begun there.

Sentence

Despite the fact that Radislav Krstić was found guilty of genocide, in the end he did not receive the longest prison term among those involved in these cases.

Krstić was sentenced to 46 years in prison, but after an appeal, the term was reduced to 35 years. He was sent to prison in Britain. In 2010, a group of Muslim prisoners attacked and stabbed him. After that, Krstić was transferred to the Netherlands, and later to Poland. He has been serving his term there since 2014.

Momčilo Krajišnik awaits his sentence at the UN war crimes tribunal in The Hague on September 27, 2006.

Getty Images / «Babel'»