Ivanivka was captured quickly, recalls the community head Olena Shvydka. In the first convoy, the locals counted 140 units of military equipment, in the second — about 200. After that, the locals stopped counting. Having captured the village, the Russians established a curfew, the order of which was constantly changing: one could move through the streets only from 10 a.m. to 12 p.m., then from 8 a.m. to 10 a.m. No one was allowed to come to the places where the Russian equipment was stationed. Occupants usually placed it right next to residential buildings.

One of the residential buildings of Ivanivka. After the shelling of the Russians, only the foundation remained of it. The owner of the house was hiding in the basement of the local school at the time of the missile hit.

Memorial to Civilian Victims of War / "Babel"

People were forced to attach first white and then red ribbons to themselves and to the gates of houses. The Russians didnʼt explain why it was needed, but if people refused, they threatened to shoot them. The occupiers evicted locals from their houses and settled there themselves, searched and looted the property.

Olena Shvydka says that there are officially seven civilian victims of the Ivanivka occupiers. One of them is her uncle Ihor Zuyuk, a veteran of the war in Afghanistan. He was killed on March 9.

The life and death of Ihor Zuyuk

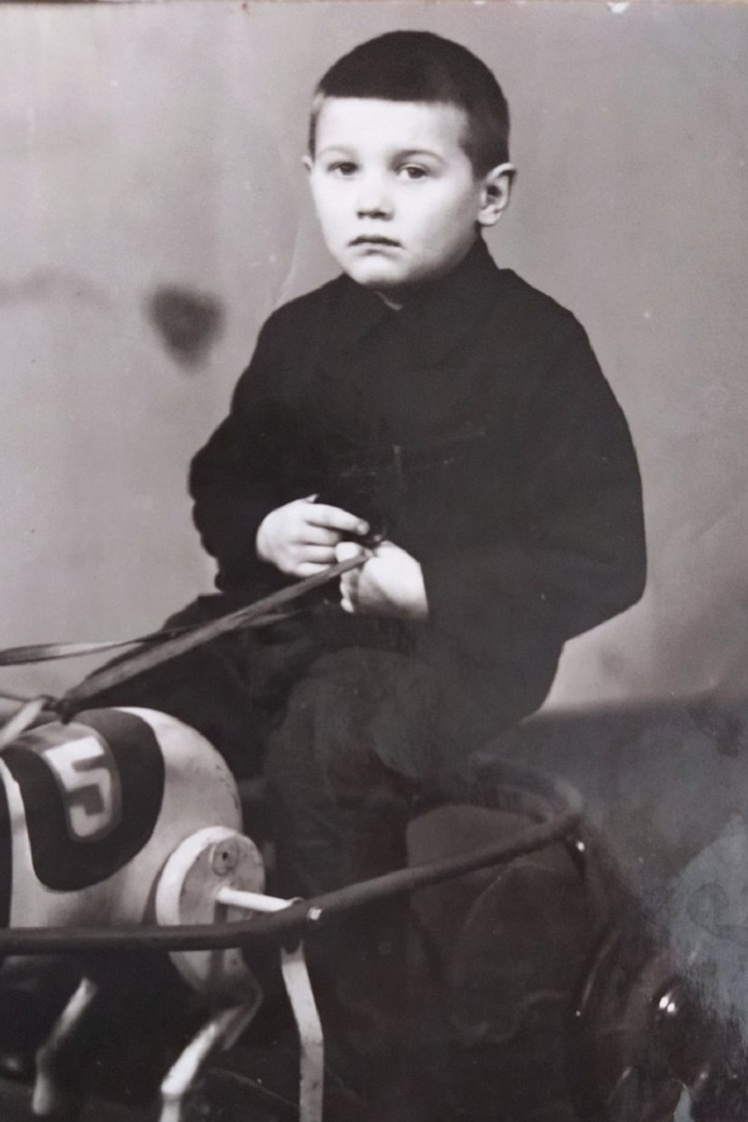

Ihor was 57 years old, he was born in Ivanivka. Here he studied at school, met his wife Olga, raised his son and daughter. Olga Zuyuk recalls that she fell in love with Ihor after graduating from school, but a serious relationship began when he returned from Afghanistan. As a conscript soldier, Zuyuk was sent to war as part of a mechanical-transport company.

Memorial to Civilian Victims of War / "Babel"

Olha worked as a Ukrainian language teacher. Ihor worked on a local collective farm on KamAZ truck, hauling grain. Then he worked in Chernihiv as a security guard at the regional electricity company.

Igor and Olga Zuyuk.

Memorial to Civilian Victims of War / "Babel"

“He was a wonderful husband and father,” recalls Olga. “Behind him was like behind a stone wall. Ihor knew everything: how to cook food, how to fix something, and how to entertain children.”

Ihor knew well what war is. However, he hardly spoke about his combat experience, trying to live a peaceful family life. At the beginning of 2022, relatives asked Ihor what he thought about the possibility of a major war between Russia and Ukraine. He replied with a joke, meaning that itʼs impossible.

Memorial to Civilian Victims of War / "Babel"

On the morning of February 24, Ihor was supposed to go to work at the Chernihiv regional energy company. As always, he woke up at dawn and quietly, so as not to wake his wife. Got ready for work.

Olha was awakened by Russian shelling.

“Whatʼs going on?” she asked.

“Olya, it seems like the war has started. Probably, thatʼs all,” replied Ihor.

He went to work, Olha stayed at home. During the day, she called him and persuaded to take their daughter and her baby from Kyiv. Ihor convinced: Kyiv is better protected and it will be safer there.

“I did force him to go and pick up the children from Kyiv. He brought daughter, one-month-old granddaughter, son-in-law,” recalls Olha. “A cousin with her 13-year-old daughter also came to our house. My mother was taken from another street, she was 82 years old... The house is big — so everyone together, in a group, decided to live through these terrible times.”

Memorial to Civilian Victims of War / "Babel"

On March 5, the occupiers entered Ivanivka. In the area of the street where the family of Olha and Ihor lived, the Russians had accumulated a lot of heavy equipment. The next day, electricity and mobile communication stopped working. There was no heat in the large house, which was heated by an electric boiler. The family decided to move to Olhaʼs motherʼs house — although it was smaller, it had gas heating. They went to the neighboring street, took a few things. After seeing his family, Ihor returned home: he did not want to leave the house and everything around without care.

This was the house of the Zuyuk family before it was burned down by the invaders.

Memorial to Civilian Victims of War / "Babel"

“He brought us a blanket and some other things by car. I asked him to stay with us, but he refused. He said that there were cats, a dog, ducks, and chickens at home,” Olha recalls. “I remember how he said: ʼWell, letʼs kiss.ʼ And I replied: ʼNo, letʼs kiss at the next meeting. Take care of yourselfʼ.”

Olha never saw her husband again.

Memorial to Civilian Victims of War / "Babel"

Olhaʼs mother died on March 8. On March 9, the Russians entered the house where the whole family was — they lined everyone up in the yard, checked their documents, and asked how many men were there. Then they pushed Olhaʼs son-in-law and son to the fence, put them at the gate and started threatening to shoot them. Olha fell to her knees between her relatives and a man with a machine gun, saying: “Kill me first.” She explained that there was a baby in the house, that there was a dead woman in the house who needed to be buried. Until one of the Russians said: “Letʼs go out of here.” It was forbidden to take the deceased to the cemetery and go outside the yard.

“The next day, around six oʼclock in the morning, a former student runs up to me and says: ʼOlha Mykhailivna, you have nothing left!ʼ” says Olha. “My son and I ran to our home, and there was a fire and ruins. The house was burned down the day before. The son was running around, looking for dad... But I understood that my Ihor wasnʼt there, because he would have come, he would have run [to us], if he had survived. A Russian soldier was still standing nearby and said: “A projectile flew towards you. Itʼs yours who fired it.”

Memorial to Civilian Victims of War / "Babel"

The woman understood that this wasnʼt true, because there was no projectile remains anywhere, only a fire. Olha asked the occupier what really happened to her husband. He answered indifferently: “We saw him in the morning. Probably, he didnʼt have time to jump out of the house.” Then the woman and her son were chased away. They were not allowed to search for Ihor or to dismantle the debris. The only thing they managed to do was take a cat and a dog from the house.

“I have never seen animals cry like that in my life. Tears flowed from both the cat and the dog. They wept like people,” Olha recalls.

In ten days, her son, son-in-law and nephew decided to go to look for Ihorʼs remains. They said that burnt body parts were scattered on the ruins of one of the rooms.

Memorial to Civilian Victims of War / "Babel"

“They brought it to me in an accordion suitcase. When Ihor was still a schoolboy, he went to a music school. Thatʼs how this accordion remained as a memory. He used to play a little for the children when they were small, but he didnʼt really take it in his hands,” cries Olha. “We buried him in that suitcase. There, in our garden. Both my mother and my husband were buried there.”

How did Ihor die?

The occupiers left the village on March 30. When they brought out their equipment, they forbade people to leave their homes under the threat of being shot. And on March 31, the Ukrainian military entered Ivanivka. After that, Olha and her children were able to rebury their relatives.

Neighbors said that they saw how on March 9, two Russian soldiers brought Ihor into the house at gunpoint, and then set the house on fire. According to one version, the Russians turned on the gas in the house and threw a grenade inside. Presumably, Ihor had already been shot at the time of the arson — several automatic cartridges were found in the room where his remains were.

The burnt house of the Zuyuk family.

Memorial to Civilian Victims of War / "Babel"

Yulia, Olhaʼs former student, says that during one of the searches in their house, she asked the Russian soldiers what happened in the teacherʼs house. He answered: “Everyone was evacuated, but father... He shouldnʼt tell our positions."

Another neighbor on the street told Olha that right before the retreat, one of the occupiers, of Dagestani origin, approached him and said: “I have to tell you a story: two of our scumbags killed an Afghanistan war veteran there, I didnʼt have time to save him.”

The first months after the tragedy, Olha was with her children. First a few weeks in Europe, then in Kyiv. However, closer to autumn, she returned to Ivanivka. She lives in her parentsʼ house, dreams of rebuilding the house destroyed by the occupiers — to preserve the memory of her husband. She says that Ihor took great care of it and was always proud that they were able to build a house like that.

Translated from Ukrainian by Anton Semyzhenko.

Everyone can join in collecting the names of those who died in the war between Russia and Ukraine. To report information on the losses of Ukraine, fill out the forms: for dead military and civilian victims. And you can help Babel to tell these stories: 🔸 in hryvnia, 🔸 in cryptocurrency, 🔸 Patreon, 🔸 PayPal:[email protected]