Finnish ski patrol after the battle, February 1, 1940. A Finnish patrol dismantles a downed Soviet aircraft on January 7, 1940. Finnish machine gunners during the Winter War, February 21, 1940.

Sa-kuva

In the 1930s, Finland spent minimal amounts of money on military needs, kept out of conflicts, and was focused on domestic development. In 1932, it signed a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union and at the same time completed and strengthened the “Mannerheim Line”. In 1938, Moscow already tried several times to impose a new treaty on Helsinki. At first, it demanded the Finns to host Soviet military bases, then to cede several border islands in the Baltic Sea to the USSR. Finnish diplomats rejected all these proposals.

In August 1939, one week before World War II began, Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. According to its secret protocols, Finland, along with the three Baltic states, came under Soviet influence. In the beginning of November 1939, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, under pressure, signed "Friendship and Mutual Assistance" agreements with the Soviet Union.

SK16 Bunker on “Mannerheim Line”, September 19, 2009. Entertainment tour for the military on the Karelian Isthmus, November 1, 1939. Vyacheslav Molotov (left) and Joachim von Ribbentrop (right) during a meeting in Moscow on September 28, 1939.

Wikimedia

The USSR tried to persuade Finland to enter into a similar agreement, now adding a new requirement to the previous ones: to move the border 90 kilometers west of Leningrad (now St. Petersburg). "There is nothing we can do about geography... Since Leningrad cannot be moved, we will have to move the border away from it", – said Joseph Stalin during the talks.

Finnish diplomats did not agree to such conditions, the negotiations came to a standstill. Finally, Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov told the Finnish delegation: “We civilians did not achieve any progress. Now it’s up to the soldiers".

In the spring of 1939, the Soviet Union began preparing for a possible war against Finland. To obtain a formal excuse for the invasion, on November 26, 1939, Soviet troops shelled their own positions near the border village of Mainila with artillery, blaming Finland and refusing to jointly investigate the incident.

On November 30, 1939, four Soviet armies invaded Finland. They crossed several sections of the finnish border, from the Karelian Isthmus to the Arctic. On the same day, the Soviets began bombing the Finnish capital, Helsinki, from aircraft. The USSR Army significantly outnumbered the Finnish in terms of personnel and equipment. Therefore, the Soviet leadership, led by People’s Commissar for Defense Kliment Voroshilov, hoped for a quick and easy victory that could be achieved in 10-12 days at best, and until the 60th anniversary of Stalin on December 21,1939 in the worst scenario.

«Бабель»

The Soviet Union did not even officially declare war on Finland. But the day after the invasion, on December 1, 1939, in the Soviet-occupied border town of Terijoki (now Zelenogorsk, Russia), a puppet Finnish Democratic Republic (FDR) with a “people’s government” of Finnish communist immigrants was formed. Moscow immediately signed an “agreement on mutual assistance and friendship” with FDR, and the invasion was declared a “war of liberation”.

After the first weeks of the war, it became clear that the USSR won’t get a quick victory. It became apparent that the Soviets underestimated the enemy’s fortifications and the geography of the terrain where the operation was taking place. Different types of troops acted incoherently: artillery did not support the infantry, infantry did not keep up with the tanks, air defense fired on their aircraft, and aircraft inflicted friendly fire, bombing Soviet troops. The Soviet command, hoping for a quick operation, did not bother to provide personnel with warm clothes. As a result, thousands of soldiers in light overcoats died from frostbite when the temperature dropped just below ten degrees [Celsius].

Soviet soldiers, killed on the outskirts of the village of Suomussalmi in northeastern Finland, December 1, 1939. This [battle] is one of the biggest defeats of the Soviet army in the Winter War. Frozen Soviet soldier among the remnants of the destroyed military column, January 14, 1940. Officers of the 18th Rifle Division, who tried to escape from the encirclement near Lake Ladoga, February 2, 1940. Eventually, almost the entire division was eliminated.

Sa-kuva

Eventually, only the polar troops succeeded. On the Karelian Isthmus, the Soviet troops could not advance behind the Mannerheim Line because they were completely unprepared to destroy pillboxes and bunkers. At the same time, even the Finnish commander-in-chief Carl Gustav Mannerheim admitted that due to lack of funds it was possible to build a line of defense that was far from perfect. “We, of course, had the line of defense ... but its strength was the result of the resilience and courage of our soldiers, not the reliability of the buildings”.

The two Soviet armies also did not do well in the central parts of the frontline, near Lake Ladoga and in North Karelia. Here the Finns fully applied their “motti” guerrilla tactics. In its essence, this tactic aimed to identify, divide, and then destroy the enemy. Mobile ski troops were perfect for this task. They did not come into direct confrontation with the prevailing Soviet forces. Instead, they acted in the rear, setting up ambushes and retreating to bases in the woods that were prepared in advance.

During the Winter War, Finnish guerrilla units often used deers for mobility. Uniform of a Finnish soldier, who was a member on a ski patrol during the Winter War.

Sa-kuva

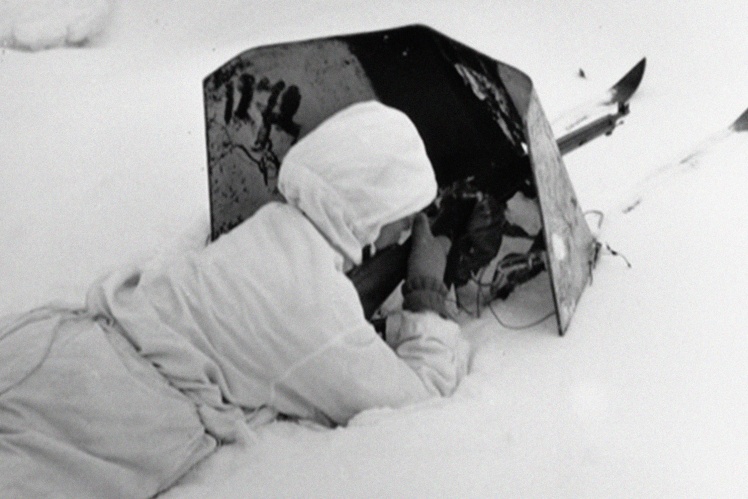

Finnish guerrillas developed their tactics of attacking mechanized columns, stretched along narrow roads through snow-covered forests and swamps for dozens of kilometers. On the impassable section of the road they disabled vehicles at the front and the end of the column with machine guns or mines. Then snipers, almost invisible in white masks, tried to destroy drivers, liaison officers, and commanders. All of them stood out in the snowy forest in their dark uniforms. This way, the Finns divided the enemy divisions into small groups, stopping their advance and destroying them from ambushes. The guerrillas also often ensured that no one could escape from the encirclement or bring reinforcements. The soldiers who remained in the column were gradually dying from frostbite and food shortages.

Finnish ski patrol, March 1,1940.

Sa-kuva

Thanks to the motti tactics, a Finnish group of about 11,000 soldiers defeated the five times bigger amount of enemy’s forces. Several Soviet divisions were completely destroyed. Some of their units remained surrounded until the very end of the war. Later, a similar tactic was used against the Soviets in Afghanistan, and against the Russian troops in Chechnya.

At the beginning of the war, the Finns lacked weapons and equipment. Some of the tanks they used dated back to World WarI I. Most of them were suitable only as fixed firing points. But Finnish guerrillas used improvised explosive devices and grenades. Bottles with flammable mixture became the main innovation and effective anti-tank weapon. Initially, they were nicknamed “Molotov cocktail” after the main mouthpiece of Soviet propaganda Vyacheslav Molotov. Speaking on the radio, he said that Soviet aircraft were dropping on Helsinki not bombs, but “bread for hungry Finnish workers”. Molotov cocktails are still used in different conflicts around the world.

Homemade explosives and “Molotov cocktails” used by Finnish soldiers, November 1939 — March 1940. Helsinki after the first bombing of Soviet aircraft, November 30, 1939. Citizens of Helsinki descend into a bomb shelter during a Soviet air raid. November 30, 1939.

Sa-kuva

Thanks to successful guerrilla tactics, many Soviet weapons, equipment, and other trophies were seized in the first month of the war. The Finns got about 40 tanks, almost 100 different artillery pieces, about 20 armored vehicles, 350 machine guns, several thousand rifles, battle flags, and military maps.

Finnish military analysts study captured Soviet trophies, January 3, 1940. Soviet tank, captured by the Finns on the Karelian Isthmus, December 1939.

Sa-kuva

At the end of December 1939, the Soviet leadership realized that any attempts to continue the offensive would only lead to new losses. There was a lull at the front. The new commander Semyon Timoshenko took into account past mistakes. He spent January and the beginning of February 1940 gathering intelligence, reinforcing, regrouping and training troops, and arranging supplies. The storm of “Mannerheim Line” had become the primary task.

Christmas Eve at the Finnish Army Headquarters, December 25, 1939.

Sa-kuva

The Finnish command understood that despite the success in the first month of the war, the country still would not be able to withstand the Soviet Union on its own. From December 1939, Great Britain and France began supplying Finns with weapons. But the Finnish army lacked personnel reserves. Little more than ten thousand volunteers from Sweden, Norway, and other countries could do little to oppose the bloated Soviet army of more than 760,000 people.

London and Paris could not coordinate the sending of a joint unit of paratroopers and aviation to Finland. The next meeting regarding this was scheduled for March 12, 1940. But it was too late. Soviet troops, suffering heavy losses, broke through the Mannerheim Line. Under the threat of full occupation of the country, the Finnish government asked Moscow to negotiate.

Swedish volunteers, fighting on Finland’s side, pull mortars on a sleigh, departing on a combat mission. January 8, 1940.

Sa-kuva

At noon on March 13, 1940, the countries ceased the warfare. A new peace treaty between the USSR and Finland entered into force. Under its terms, the Finns lost about 40 thousand square kilometers of land, a tenth part of their territory. The border was pushed 150 kilometers back from Leningrad. The second largest city in Finland, Viipuri, became part of the USSR and was renamed to Vyborg. About 430,000 Finnish residents that lived on the territories ceded to the Soviet Union were forced to flee their homes and relocate inland.

Soviet soldier with a protective shield during the storming of Viipuri (Vyborg) city. March, 1940. Finnish troops retreat from the city of Viipuri (Vyborg) after the signing of the peace treaty on March 13, 1940.

Sa-kuva

The USSR was expelled from the League of Nations as an aggressor. The Democratic Republic of Finland disappeared as quickly as it came into existence. Timoshenko became the new People’s Commissar for Defense instead of Voroshilov, who was no longer involved in major military operations. Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev later recalled: “All of us - and Stalin first and foremost - sensed in our victory a defeat by the Finns. It was a dangerous defeat because it encouraged our enemiesʼ conviction that the Soviet Union was a colossus with feet of clay”. Eventually, he appeared to be right. The German command, observing the course of the Soviet-Finnish war, came to the conclusion that the USSR could not resist the German army. The following year, 1941, Finland joined the Nazi invasion of the USSR.

Translated from Ukrainian by Olya Panchenko.

We tell about historical events honestly and objectively. You can support Babel here.

Viipuri Cathedral (Vyborg) after the bombing, February 5, 1940.

Sa-kuva

![Soviet soldiers, killed on the outskirts of the village of Suomussalmi in northeastern Finland, December 1, 1939. This [battle] is one of the biggest defeats of the Soviet army in the Winter War.](https://babel.ua/static/content/nqyjccwr/thumbs/748x/8/cb/71c722e063b38e2411d1c766bcd2ccb8.jpg?v=7392)