Did the Russian military steal the original exhibits from the museum? Officials in Zaporizhzhia say it was a copy of Scythian gold.

These were the originals, of course. I was shocked to hear about the “copies”.

Oleksandr Starukh said that the most valuable things were taken out of the museums of Zaporizhzhia oblast in March. Vladyslav Moroko, director of the Department of Culture and Information Policy of the Zaporizhzhia Oblast Civil-Military Administration, said that there were no originals in Melitopol in the first place.

There was no evacuation in our museum. I left Melitopol on March 25, and on March 26 my staff came to the museum, and the orcs [Russians] were changing the locks there. When I heard the statement about evacuation and copies, I was very upset. It turns out that the state of Ukraine abandoned the originals, saying that the Russians stole copies. And then the orcs will say, "Thatʼs what you said, that we have copies. Look for your originals yourself. And when our [military] will come — I pray for it every day — they will ask: "Ibrahimova, they took the copies, but where are the originals?" Are you kidding or what?

After the report of the theft of the collection, did the Ministry of Culture and the oblast department of culture contact you?

The Ministry of Culture has not contacted me either before February 24 or after. But we are a communal museum, we are subordinated to the city council, and our governing body is the Melitopol Department of Culture. And there is a section of museum affairs under that department in the oblast administration.

Why the director [of the Department of Culture and Information Policy] stated that we have copies and that we never had Scythian gold, I donʼt understand. He called me after the collection was stolen to remind me of my responsibility. I asked, "What do you mean?" He told me: "You are responsible for this. You didnʼt save it." I said, “Wait a minute. Letʼs talk about this in detail."

All this time, when we were warned by all the worldʼs intelligence services about the war, no one was doing anything. I called the oblast department and asked what we should do. In response, I heard that there are no instructions from the management.

On February 23, at about 12 pm in the afternoon, an employee of the oblast [culture] department called the museum. He asked for information on our financial needs for the evacuation of the main museum fund to Ternopil. The document was needed right away till 1 pm the same day. And all this in oral form, without an order. I was not at the museum — I took a leave of absence. So I ran to the museum. It turned out that we need an estimate for the evacuation of the entire main fund. And our main fund is 50,610 subjects.

We counted everything: packing materials, movers, security guards, and even how much it will cost to evacuate with minibuses, and how much — with trucks. It cost half a million. I sent the estimate at 3:41 p.m. The department called back and said: "As usual, everything is clearly written."

And at 5 am in the morning on February 24 our airfield was bombed. And when the director of the department reminded me of my responsibility, I told him that I have no right to dispose of the main museum fund of Ukraine as I want. The items are only stored at the museum, they are not our property. If an object is removed from the museum, you should replace it with a wet stamp document.

I could hide the collection not in the basement, but I did this at my own discretion with the hope that they [the Russians] might not find it. But if the collection was outside the museum and [the occupants] couldnʼt find it, my people would be tortured. Ears and fingers would be cut off. In my opinion, the Ministry of Culture is to blame for what happened, it didnʼt think about anything and did nothing [in advance].

Gold from the burials of Sarmatian times, found in the 1970s. The golden collection of the museum consists of almost 300 items. Hun diadem and gold plates that adorned clothes, weapons, and horses.

The archive of the Melitopol Museum of Local Lore

Were you told that the collection had to be buried somewhere outside the museum? To take out the exhibits?

Just imagine, letʼs simulate the situation. First, where is the guarantee that you will later find the collection where you buried it? Secondly, there are no documents in the museum confirming the evacuation, which means the orcs would have tortured my staff until they found it.

Did Moroko say that?

Letʼs not name any names. They called from the oblast. I told them that every January we report on the presence of precious metals in the collection. Specifically — what is there and how much. They had to know everything.

A question from the category of fiction. Was it possible to evacuate the collection on February 24, in a hurry?

No one from the oblast contacted me that day. Only the city authorities said: "Let people go home people because if someone is killed on the way, you will be responsible for it." On February 24, the city was in panic, it was bombed. I donʼt think it was realistic to evacuate. People werenʼt able to pick up all the documents and hide them. And again, who should have been doing that? I canʼt take the archeological gold out of the museum without an order from the management, and there was none.

"We went down to the basement and crawled on our knees, burying the collection "

Your museum has a collection of Scythian gold, jewelry of the Hun and Sarmatian periods, a collection of coins, orders and medals, and historical weapons. Was it the most valuable thing that you buried somewhere in a museum? Tell us where you hid the collection.

It has to be told the way things happened. On the morning of February 24, under the explosions, we ran to the museum. We started hiding documents. We have such rooms, which we call "Chernikovʼs safe".

The museum is located in the former mansion of the merchant Chernikov. On the ground floor, there are rooms without windows that do not face the street. We thought that if we were hit [with a missile], what we hid there would be preserved. So we brought some things and documents to these rooms: accounting books, inventory books, etc. We have been in the museum till around 1 pm, and then I let everyone go home because the bombing didnʼt stop, and the city authorities gave the command to "run home".

The Russians reached Melitopol quickly, street fights lasted until February 26. The airfield was on fire, the tank was hit, we had no light for 24 hours, and all the supermarkets were smashed. It was chaos. Then our troops retreated, the shelling subsided a little, and we came to the museum on February 27 or 28.

The collection of Scythian gold and everything you mentioned is securely stored under 24-hour protection. We were sure it was safe. These exhibits constantly remain in a barred room. We write orders even to get there. And only twice a year we do a one-day exhibition for the locals.

On February 28, we decided to dismantle the permanent exhibition and hide historical weapons — we have a collection from the XVI to the beginning of the XX century. We also hid everything fragile, such as dishes.

We took away the historical weapon because we were afraid that looters would run in and take it. I remember the experience of the [Oblast] Donetsk Museum of Local Lore in 2014. I was with their research fellow on a study trip then. She was called and told that the main custodian was threatened with the gun and that 400 historical weapons had been confiscated from the museum.

Rifle with a wheel lock of the 17th century from Western Europe, which consists of a steel barrel built into a wooden bed, a wheel lock is attached to the right, with no ramrod. Turkish sword with scabbards of the late 16th — early 17th centuries. The exposition “Our land from 15th century to 1914” consists of cold steel and firearms of the Cossack era.

The archive of the Melitopol Museum of Local Lore

On March 10, I was abducted. I was the first person detained by the Russian military in Melitopol. Sometime around 7 am, they [the occupants] broke into my house. There were many of them, with machine guns. They searched rooms, attic, and basement. I live in a private house. There were eight of us in the house: my husband and seven women. There was a shooting in Melitopol, and we have a basement, so some of my colleagues and friends moved in with us after February 24.

They searched the house and asked who Lieila Ibrahimova was, and I responded. It was clear from their behavior that they knew my face. They knew that I was a member of the local council and was engaged in Crimean Tatar activism. Thatʼs why they detained me. At first, I was very confused, but after recovering a little, I began to ask why they came. "On the basis of martial law," they replied.

Wasnʼt it about a collection of Scythian gold?

I found myself in a cell with a toilet, and they started asking me about my connections with Refat Chubarov and Lenur Islamov. They wrote down on some piece of paper my passport data and where I work, and then switched the conversation to a museum.

Three Federal Security Service officers were interrogating me, their faces covered with balaclavas, and I saw only eyes that I will never forget. They asked what topics are covered in our museum, and what are the sections. I told them: “Do you understand what a museum of local lore is? You have local history museums in Russia. Itʼs about everything — nature, history, famous people, paintings."

Then they asked about Islam, about history, about why I went to rallies. They pressed on the rallies. From March 1, when the first rally against the occupation was organized, up to March 9, I was at the events. And after my release from captivity, I went because it was a rally in support of our mayor Ivan Fedorov, who was abducted on March 11. I just couldnʼt not go there.

One of the orcs tried to press me, saying that there were already people who betrayed us all and told them [the Russians] everything they wanted to know. I replied that it was not my plan to cooperate with them. They said they were not threatening me, but warned me that now they are the authorities in the city. I said that everything is to the will of the Almighty.

It lasted about three hours like this, then they put a black bag on my head, put me in the car, and drove very quickly. The car meandered through the city so that I would not understand where they were taking me. As it turned out, they took me home.

In the evening, the staff called me and said that while I was interrogated, the museum was searched. Orcs smashed the locks. They went to the fund, where the Scythian gold is stored.

On March 11, we came to the museum. We have video cameras installed on each floor, we are lucky that the [Russian] military didnʼt find a video recorder. So we copied the video and passed it on to the local culture department. The video shows everything: how the military came in, how they searched for documents, brought in some trough with tools — a chainsaw or something like that, smashed the locks and doors of the fund with precious metals. They went there but did not touch the exhibits. Then they took a white bag full of something out of the museum. The search lasted for 50 minutes, the video indicates.

At that time there was a staff member on duty and two unarmed police officers — they had already been disarmed at that point. I understood that the one on duty was persuaded to cooperate. I asked her, "Anechka, what did they take?" She said that only the green folder was taken out, it seems, from the accounting office. But itʼs a full white bag they take in the video. We brought groceries for out employees in bags — some organizations helped us because of the food crisis. The video shows them stuffing a bag with something and taking it out.

Lieila Ibrahimova conducts a tour in front of the exhibition with Crimean Tatar clothes.

The archive of the Melitopol Museum of Local Lore

What were they looking for?

For constituent documents, but we hid them on February 24. While we were dealing with the video, the mayor was abducted. We realized that something terrible was happening. We could not take objects out of the museum, due to lots of military vehicles and Russian troops in the city, and the locks were smashed by the military on March 10. So we decided to hide everything in the basement. We have a basement, but it isnʼt mentioned in any documents. There, in the construction debris, we buried a collection of Scythian gold and all valuables.

Why do you have construction debris in the basement?

Iʼll tell you. It was put there by communists. In Soviet times, there was a party committee in the Chernikovʼs mansion. When the reparation of rooms was completed, the workers sealed the entrances to the basement, only a small hatch was left. The legend says the communists were afraid that no one would get in from down there. Melitopol is an old city, so there is a connection between the houses through the basements.

The basement is long, 50 meters, but low, you can only move on your knees there. The hatch is about 90 by 90 centimeters, enough for one person to squeeze. We put up a ladder, went down and crawled on our knees to the end, and buried the collection in the boxes. And made sure that nothing was noticeable. We removed the tracks on the floor, as if we werenʼt there, and carried the ladder to the third floor.

What happened next?

We agreed that if they [the Russians] would ask about the collection, the museum workers would reply that from February 24 to 28, no one was in the museum except for the director, and no one knows what she hid here. I said: blame everything on me so that you are not dragged or arrested. What else could I say?

On one side from us there is a Palace of Youth Creativity, on the other — the school $25, the military started to live on both locations. I realized that the museum is in great danger, and I told the girls: "Letʼs do this: run, see if everything is okay, and go home." And so we did this every day until March 26. On that day, the workers came, locked themselves inside, went around the floors, and then they heard voices in the hall. They went down, and there the lock was being changed. The military were standing there, someone in civilian clothes, they had tools with them.

They changed the locks and said that now it is their responsibility to come to the museum. But the girls continued to come for a while and inspected the building from the outside. They still had the keys to the yard. And so one day they saw that the light was on in the museum and someone was there.

And then a collaborator Yevhen Horlachov found our main custodian Halyna Andriivna Kucher — he stopped her in the street. He said, "Iʼm your new director, letʼs work." And she replied that she is a pensioner and is taking care of her bedridden mother, so she is not interested.

"If they didnʼt find the collection, they would have started abducting the staff"

The search for the gold began after Horlachov appeared?

On April 20, they "appointed" him [as a museum director]. He has been visiting us since childhood, he knows every corner of the museum. He was engaged in the reconstruction of [the museum section about] the battles around Melitopol during World War II. He was a soldier of the Ukrainian National Guard, in 2014 he served in the anti-terrorist operation [on Donbas], but then somehow disappeared, and we didnʼt see him.

In general, I thought that they would call the director, that was there during Soviet times. She has “Soviet brains”. But Horlachov was dragged because he is an ally of our former MP Yevhen Balytskyi, who actually brought orcs to Melitopol and cooperates with them.

After his appointment, Horlachov called the museum staff and invited them to work, but everyone refused. I tell the museum staff: “Donʼt cooperate, thatʼs for sure, but donʼt pick any battles. So there was no physical violence, you know?"

They started looking for a [hidden] collection, putting pressure on employees. Halyna Andriivna Kucher was brought to the museum three times and threatened that she wouldnʼt return home. But I do not doubt Halyna Andriivna and I do not doubt our employees. No one could tell where we buried it.

Before the revolution of 1917, the museum mansion belonged to the merchant of the 2nd Guild Peter Egorovich Chernikov. The local lore museum of Melitopol started working here in 1967.

The archive of the Melitopol Museum of Local Lore

How did they find the collection then?

Halyna Andriivna said that they once again brought her to the museum. FSB officers began to search everything — the attic, each box and drawer. And when they didnʼt find anything again, they said to Horlachov: "Did you check the basement?" He says: “There is nothing to look for there, it is littered with debris. I was there once." But the military ordered to open the hatch.

They looked, but there was no ladder. The military said it wasnʼt deep and jumped down. There was no flashlight, so he turned on the flashlight on the phone. He crawled for about half an hour, and I donʼt know what he was pulling, what he was stabbing, but he got out happy and said that he had found something. Then the others jumped down and started getting out our boxes with exhibits.

So someone told them?

I donʼt think so. They searched everything several times and when they didnʼt find it anywhere, they went down to the basement by the method of exclusion. But I want to emphasize that if they did not find the collection, they would start abducting [members of] the team. On April 30, they abducted Halyna Andriivna once again. As I understood, when our officials said that those were fakes, the occupiers called someone from the Crimea [for the inspection]. Itʼs quite close from there to us

Halyna Andriivna said that they came to her in the morning, jumped over the fence, and took her away from home. They didnʼt put the bag on her head in the car, but she was told to bend to her knees and put a warm military jacket on her head. She was brought to a building, taken to a room with a table and a chair, and interrogated. They asked her very specific questions about the collection, that is, someone told them what to ask. Towards the night of May 1, Kucher was released. I talked to her after that.

There was a statement that they want to take the collection to Donetsk. Do you know anything about this?

No, I do not know anything. But judging by the fact that they take everything from Melitopol to the Crimea — equipment, furniture, grain, everything, then the collection will probably be taken there.

"Itʼs good that the Russians admitted the theft"

Tell us about the Scythian gold collection. The Hun diadem is being discussed in the museum community. There are two of them in the country — at your museum and in the treasury of the National Museum of History of Ukraine.

We have Scythian gold from the Melitopol mound. It was found in 1954. The man dug a hole in the yard for the toilet or cellar and fell through. And got out already with some gold in his hands. And this is 1954 when neighbors watched each other. They called the police, which took the museum staff with themselves. For the first two days, they dug on their own — museum employee Nina Volchkova and director Fedir Kulyk, until a famous archaeologist [Oleksiy Ivanovych] Terenozhkin and others arrived from Kyiv.

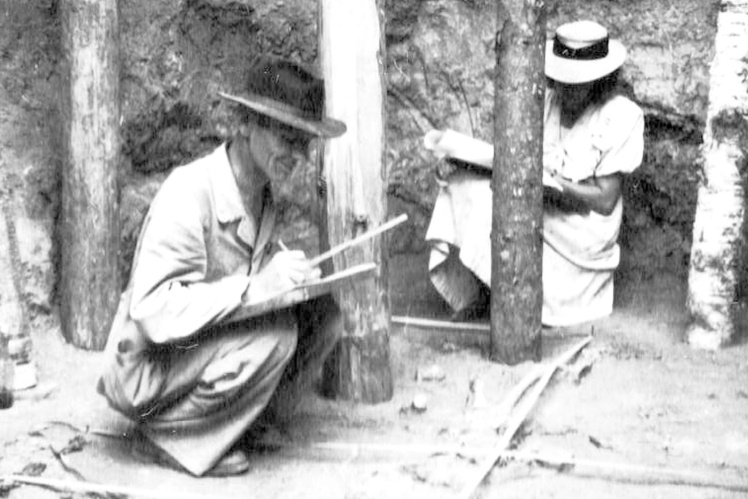

First, the mound was torn with shovels. Burials in the mound were at a depth of more than 6 meters. Alexey Ivanovich Terenozhkin.

The archive of the Melitopol Museum of Local Lore

Therefore, the first 198 items found with the participation of our staff were left in the museum, and everything else was taken to Kyiv. We were very proud, because thanks to the Melitopol mound, the Museum of Historical Treasures in Kyiv appeared. Before that, everything that was found was taken to Leningrad or Moscow, and this is the first thing that stayed in Ukraine.

We have fragments of Scythian womenʼs clothing, menʼs hats, and horse harnesses. The exhibits feature interesting stories from Greek mythology — a description of flora and fauna. Scientists have debated for a long time whether a fly or a bee is depicted there.

The Hun diadem is from the first half of the 5th century АD. It was found in 1948 in Melitopol. There was a construction company that was extracting material for a brick factory, and the workers stumbled upon something in their quarries.

The tiara is made of gold foil of a 600th rate, which was put over the leather, which hasnʼt survived to this day. Decoration inlaid with amber, pomegranate, carnelian, and granulation — this is a very interesting technique. There are triangles on the tiara, which consist of small golden beads — about three and a half thousand of them. On this small tiara, the gold part is only щт the forehead and then it was tied around the head with leather.

Hun diadem, first half of the 5th century AD.

The archive of the Melitopol Museum of Local Lore

What are the legal mechanisms to prevent this from being taken away and stolen?

I wrote a statement to the police about the theft. Our Melitopol lawyers of those who evacuated helped me to write it. Nobody from the oblast or the Ministry [helped]. It is good that the Russians are so stupid. They made a show out of finding a collection. They took photos of everything, made videos, and posted them on their propaganda channels on social networks — they themselves admitted that they stole them.

Is it only you who have to write a statement to the police? Are oblast officials and the Ministry of Culture doing anything?

I donʼt know if they do anything. The Ministry of Culture never contacted me, and oblast officials called to say that it was not their fault but mine.

I know that youʼve been evacuated. Can you tell us where you are?

I am in a safe place together with women and children of soldiers who are fighting for Ukraine. In the morning, every family wakes up hoping to hear the words that "the war is over, you can go home". Now Iʼm engaged in public work — promoting Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar culture. In general, I do not want to talk much about myself for security reasons. I left the city on March 25. I was evacuated through the first humanitarian corridor on the recommendation of the city authorities. Our authorities, Ukrainian. I received many calls with warnings, and I was told that if I was abducted for a second time, it would be unlikely that I would be released.

Translated from Ukrainian by Yulia Pryimak.

Support Babel:🔸donate in hryvnia 🔸in cryptocurrency 🔸via PayPal: [email protected].